Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

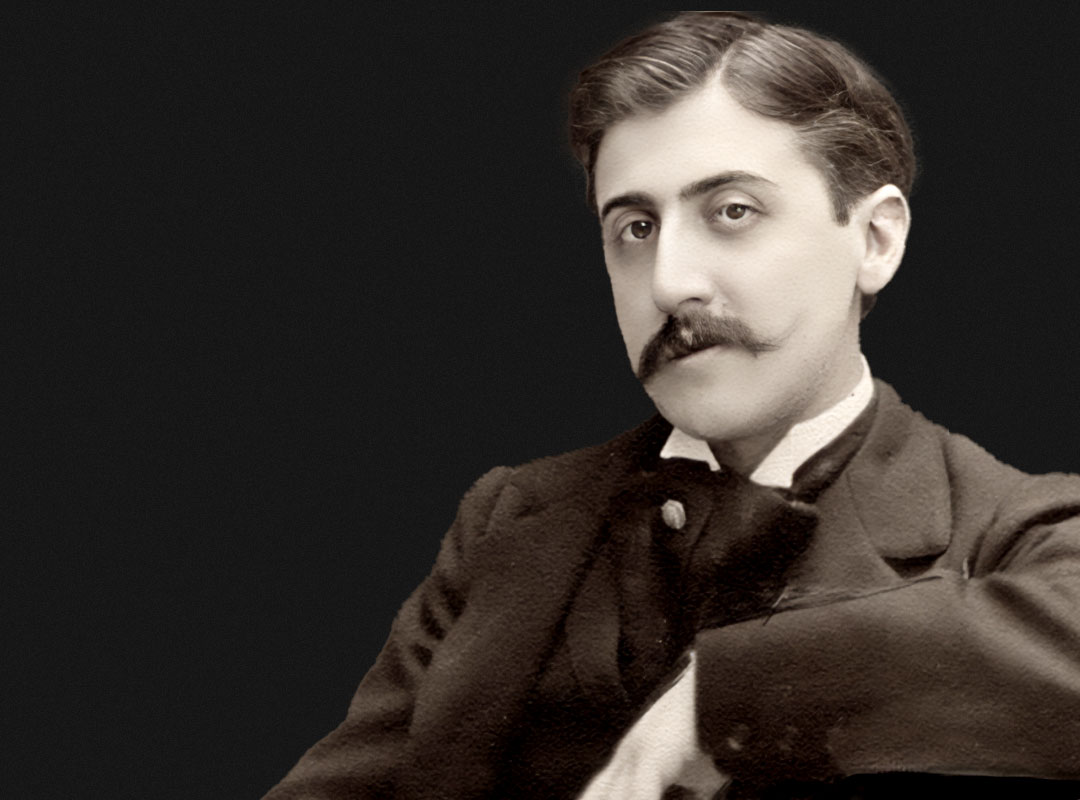

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of French novelist, literary critic, and essayist Marcel Proust, considered one of the most influential authors of the 20th century. Proust is best known for his monumental seven-volume novel In Search of Lost Time, which explores memory, time, and consciousness with unparalleled psychological depth and literary innovation. Drawing on his own life and experiences, Proust pioneered a deeply introspective and impressionistic style that influenced modern literature. He is now regarded as one of the greatest novels ever written, shaping the modernist movement and inspiring generations of writers.

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust was born in 1871 in Auteuil, a wealthy suburb of Paris. His father was a distinguished physician and epidemiologist, known for his work on hygiene and public health. He played a key role in developing measures to combat infectious diseases, particularly cholera, and was a respected authority on preventive medicine. Proust’s mother came from a wealthy and cultured Jewish family and was highly educated, fluent in multiple languages, and deeply interested in literature and the arts. She maintained a close and affectionate relationship with her son, encouraging his intellectual development and sharing his literary passions. While his father embodied the scientific rationalism of the era, his mother provided the emotional and cultural foundation that deeply influenced Proust’s literary sensibilities.

As a child, Proust was sensitive, intelligent, and deeply affectionate, but he was also frail due to his chronic asthma, which often kept him indoors and under the watchful care of his devoted mother. He had a vivid imagination and an early appreciation for literature, influenced by the refined, intellectual environment of his home. Though he enjoyed moments of sociability, particularly among his family and friends, his delicate health made him introspective, and he found solace in books, nature, and his inner world.

Despite Proust’s fragile health, he demonstrated exceptional intelligence and a precocious love for literature. In 1880, at the age of nine, he began attending the Lycée Condorcet, one of Paris’s most prestigious schools, where he excelled in literature and philosophy, and also developed friendships that would later influence his writing. He became part of an elite social circle, forming friendships with well-connected classmates, which introduced him to the aristocratic and artistic milieus that would later inspire characters in his novel In Search of Lost Time. During this time, he spent idyllic summers in Illiers, a village in north-central France, where he absorbed the sensory impressions and emotional nuances that would also later be immortalized in the novel.

In 1889, Proust began his mandatory military service in Orléans, but due to his poor health, he served for only a year before being discharged. That same year, he enrolled at the Sorbonne (then the University of Paris) to study law, philosophy, and literature, though his true passion lay in literature. These formative years deepened his fascination with high society and the arts, shaping his literary ambitions and setting the stage for his future writing. Proust immersed himself in Parisian intellectual and social life while continuing his studies at the Sorbonne. He became deeply involved in Parisian salons, mingling with aristocrats, writers, and artists.

In 1896, Proust published his first book, Pleasures and Days, a collection of essays and short stories showcasing his refined prose and keen psychological insight, though it received a lukewarm reception. During this period, he also began work on Jean Santeuil, an early autobiographical novel that remained unfinished but foreshadowed the themes of his later work. He also translated and wrote a preface for Sesame and Lilies by John Ruskin, whose ideas on art and memory profoundly influenced his literary vision.

In 1903, Proust attended a high-society ball hosted by the Comtesse de Chevigné, a woman who partially inspired the character of the Duchesse de Guermantes in In Search of Lost Time. Proust, known for his keen social observations, was so captivated by the event that he later wrote a detailed letter describing every nuance of the guests’ attire, mannerisms, and conversations. However, when the Comtesse read his account, she was offended by his sharp, almost microscopic attention to detail and reportedly banned him from future gatherings. This incident highlighted Proust’s dual role as both an insider and an outsider in aristocratic circles — immersed in their world yet ultimately destined to transform it into literature.

That same year Proust experienced the devastating loss of his father, followed by the death of his beloved mother in 1905 — an event that deeply shattered him and led to a period of intense grief, deep mourning, and seclusion. Proust became increasingly isolated, and this period of loss and transformation set the stage for the creation of In Search of Lost Time, as he began retreating into the world of memory and literature. As Proust withdrew further into solitude, his reflections on memory and loss took on a near-mystical quality, shaping not only his literary ambitions but also his broader philosophical and spiritual outlook.

Proust’s spiritual perspective was deeply personal and complex, shaped by his literary vision rather than adherence to any formal religious doctrine. Raised in a household with a Catholic father and a Jewish mother, he did not practice organized religion but was profoundly interested in memory, time, and transcendence. His work suggests a belief in the transformative power of art and memory, portraying them as vehicles for capturing lost time and achieving a form of immortality. Through involuntary memory — instances in which memories come to mind spontaneously, unintentionally, automatically, and without effort — Proust conveyed a mystical sense of revelation, where past and present merge in a timeless continuum. Rather than seeking meaning in religious faith, he found it in human experience, love, beauty, and the redemptive power of literature.

After Proust’s mother passed away, he inherited a substantial fortune, allowing him to focus entirely on his writing. Around 1907, he withdrew from social life almost entirely, spending much of his time in a cork-lined bedroom to shield himself from noise and focus on his work. Solitude and quiet were essential to Proust’s creative process, allowing him to immerse himself fully in the intricate world of memory and introspection. This isolation enabled him to explore the depths of human consciousness, crafting his intricate sentences and psychological insights without distraction. Proust saw solitude not as loneliness but as a necessary state for artistic and intellectual revelation, where he could distill fleeting experiences into timeless literary expression.

During this period, Proust abandoned his earlier novel Jean Santeuil and began developing the ideas that would become In Search of Lost Time. By 1910, he had completed early drafts of key sections, refining his distinctive literary style, which blended memory, introspection, and psychological depth. His health continued to decline, but his creative ambition surged, laying the foundation for his literary masterpiece.

Proust worked intensively on In Search of Lost Time, refining its structure and style. In 1913, the first volume, Swann’s Way, was published at his own expense after being rejected by multiple publishers, including André Gide at Nouvelle Revue Française, who later regretted the decision. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 disrupted his work, and Proust largely withdrew from Parisian society, focusing on expanding his novel. Despite his worsening health, he tirelessly revised and dictated new sections, infusing the work with reflections on time, memory, and the nature of human experience. By 1917, he had completed substantial portions of the later volumes, even as his asthma and increasing physical frailty forced him into near-total seclusion.

In 1919, In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower, the second volume of the novel was published and won the prestigious Prix Goncourt, bringing Proust long-overdue literary recognition. The award, France’s most prestigious literary prize, was expected to go to Roland Dorgelès for his war novel Wooden Crosses, which chronicled the harrowing experiences of World War I soldiers. Proust’s victory sparked controversy, as critics and war veterans felt that an aristocratic writer who had spent the war in bed revisiting his memories should not have triumphed over a firsthand account of the trenches. Despite the backlash, the award cemented Proust’s reputation and helped bring his work the recognition it deserved.

Encouraged by this success, Proust continued revising and preparing the remaining volumes for publication, often dictating edits from his cork-lined bedroom. His health continued to deteriorate, but he remained intensely focused on his work, determined to complete his magnum opus. By 1921, Proust had completed drafts of all seven volumes, though only a few were published in his lifetime. In the final year of his life, Proust worked relentlessly to complete In Search of Lost Time, despite his rapidly failing health. He made final revisions to Sodom and Gomorrah, which was published that year, and continued editing the later volumes, determined to see his masterpiece through to completion.

Proust’s chronic asthma worsened, and he became confined to his bed, suffering from pneumonia and exhaustion. In 1922, Proust passed away in his Paris apartment at the age of 51. Though he did not live to see the full publication of his work, his remaining volumes were posthumously published.

Proust’s legacy is that of one of the greatest novelists of all time, who revolutionized literature with his profound exploration of memory, time, and human consciousness. Proust’s pioneering use of introspective narration, psychological depth, and intricate, flowing prose influenced countless writers, including Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Samuel Beckett. His concept of involuntary memory became a cornerstone of modernist literature and continues to shape philosophical and literary discussions. Though largely unrecognized during his lifetime, Proust’s work is now regarded as a towering achievement, inspiring scholars, writers, and readers to explore the intricate landscapes of personal and collective memory.

Some of the quotes that Marcel Proust is known for include:

Let us be grateful to the people who make us happy; they are the charming gardeners who make our souls blossom.

The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.

Always try to keep a patch of sky above your life.

Remembrance of things past is not necessarily the remembrance of things as they were.

Every reader, as he reads, is actually the reader of himself. The writer’s work is only a kind of optical instrument he provides the reader so he can discern what he might never have seen in himself without this book. The reader’s recognition in himself of what the book says is the proof of the book’s truth.

My destination is no longer a place, rather a new way of seeing.

Thanks to art, instead of seeing one world only, our own, we see that world multiply itself and we have at our disposal as many worlds as there are original artists, worlds more different one from the other than those which revolve in infinite space, worlds which, centuries after the extinction of the fire from which their light first emanated, whether it is called Rembrandt or Vermeer, send us still each one its special radiance.

Desire makes everything blossom; possession makes everything wither and fade.

We don’t receive wisdom; we must discover it for ourselves after a journey that no one can take for us or spare us.