Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

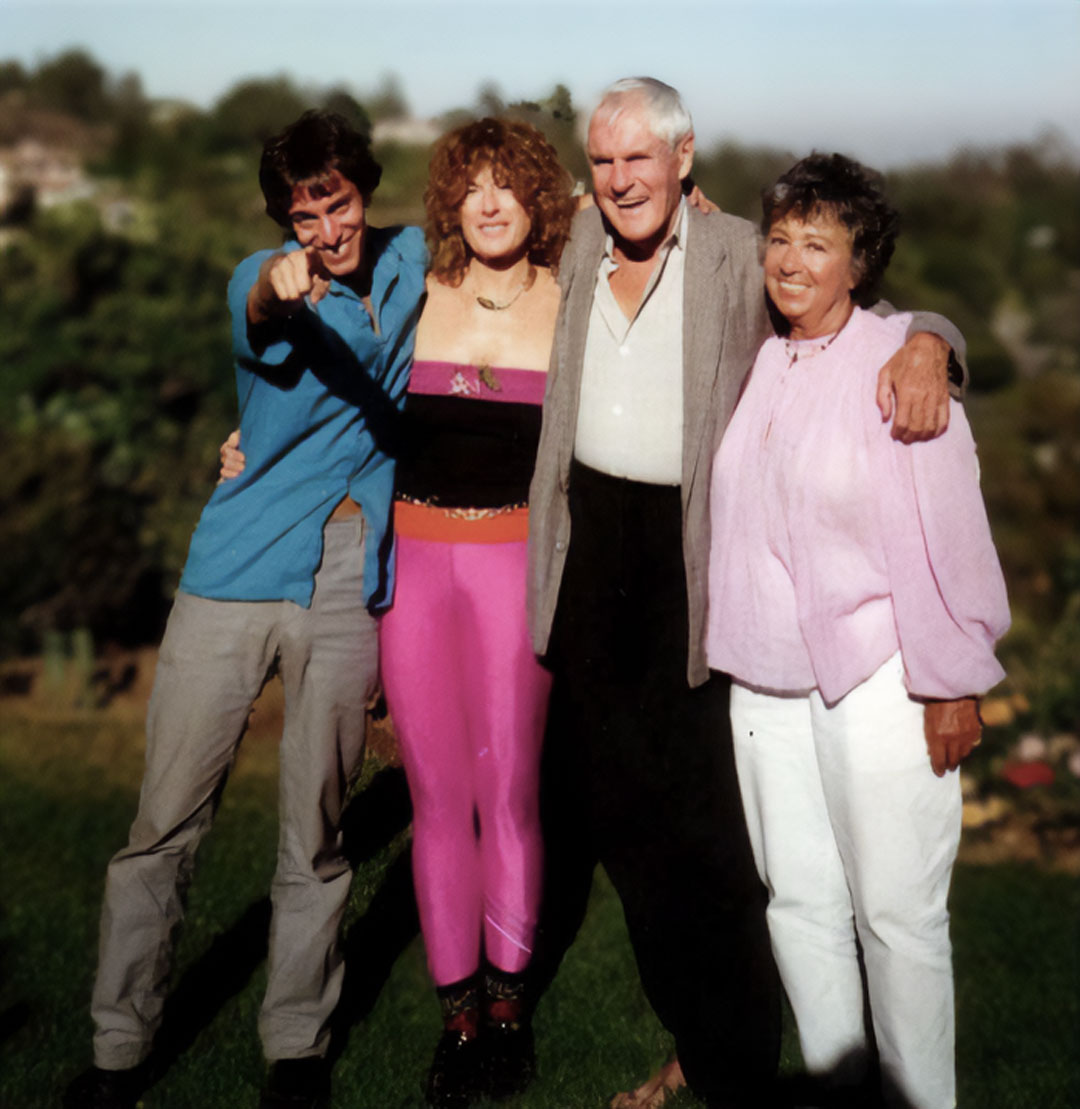

During the early 1990s Carolyn and I visited the late psychologist Timothy Leary a number of times at his home in Beverly Hills. Timothy was a good friend and a great inspiration, as well as a public icon of great controversy and one of the most influential psychologist-philosophers of the twentieth century. He was certainly one of the most brilliant, charming, and funniest people that I ever met.

Because of the sensationalized media attention that Timothy received, many of his accomplishments have been obscured and his image distorted in many people‘s minds. Timothy was a successful research psychologist, who received his Ph.D. from U.C. Berkeley, and was on the distinguished faculty at Harvard University from 1959 to 1963. The Annual Review of Psychology called his book Interpersonal Diagnosis of Personality, “the best work in psychotherapy” in 1957, and it remains a standard text in its field to this day.

When Timothy’s studies into controversial methods for altering consciousness lead to his dismissal from the prestigious university in 1963, he continued his research into visionary states at the Millbrook estate in New York, working with many influential writers, artists, scientific researchers, and philosophers. Timothy began traveling around the country— appearing at peace rallies, giving public lectures at universities, spreading messages of hope and cognitive freedom— and he became one of the most popular counterculture figures in America during the 1960s.

Timothy‘s influential public appearances, books and lectures, made him popular among young people and feared by the cultural establishment, because of his message to “drop out” from mainstream society. President Richard Nixon called him “the most dangerous man alive,” and he was sentenced to ten years in prison for less than a half an ounce of cannabis in 1970. Around eight months later Tim escaped from prison, and after being chased around North Africa and Europe by government agents for several years, and spending more time in prison, he was paroled by California governor Jerry Brown in 1976.

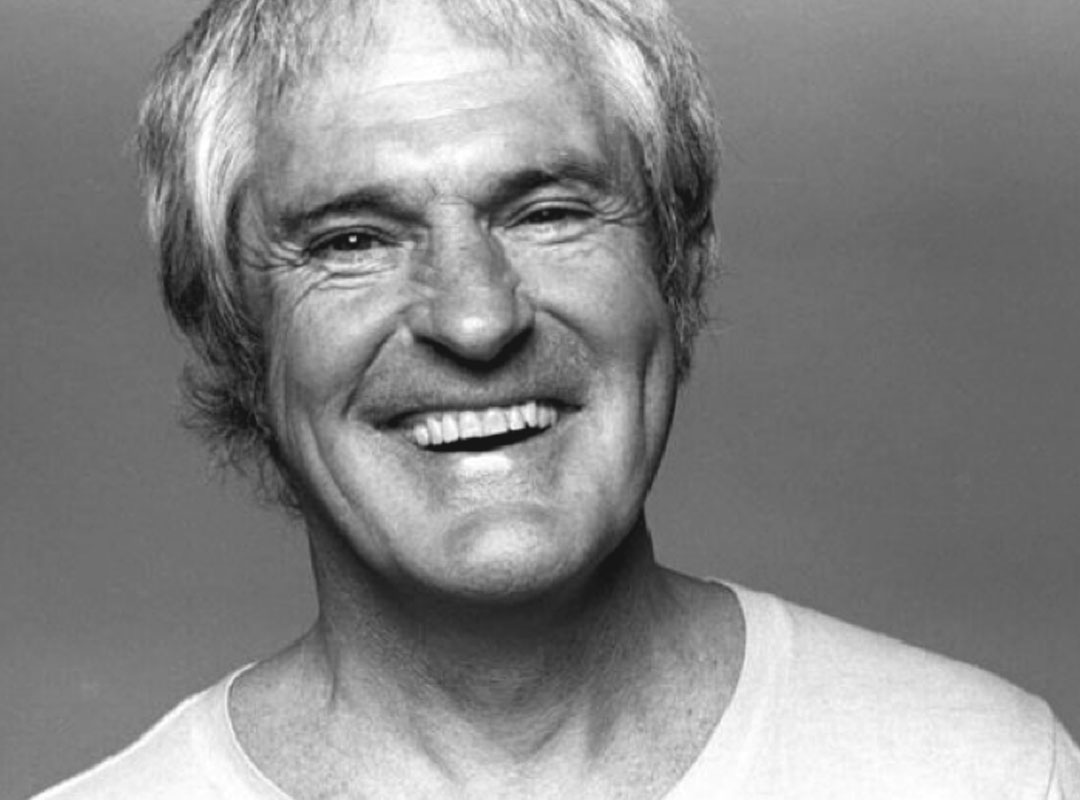

Throughout all his persecution, escape and capture, Timothy never lost his sense of optimism, or his sense of humor, and it is rare to find a photograph of Tim in which he isn’t smiling broadly. Timothy’s brave and upbeat approach to his own dying process was every bit as instructive and inspiring as his approach to life had always been. When Tim learned that he had terminal cancer, he announced that he was “thrilled and ecstatic” to be entering the mystery of death, and he made his final year on this planet a great celebration.

Timothy will certainly be remembered as one of the most original and creative philosophers of our time. He is the author of more than twenty-five books and many of his recorded lectures can be found online. Timothy was buzzing with lively electrical energy whenever we were around him, and his good-humored optimism was contagious. He had a wonderful ability to make people around him feel good about themselves. Timothy once said to me, “You have a very healing face. You radiate a kind of quiet joy. It’s amazing.” I was glowing for days after he said that to me, but most of all though, he made us laugh.

I interviewed Timothy twice, in 1989 and again in 1996, a few months before he left this world. Here are some excerpts from my conversations with him:

David: What kind of insight do you think we can gain from exploring the molecular and atomic realms?

Timothy: . . .The greatest wisdom is always housed in the smallest package. I think I even said that in the Psychedelic Prayers twenty-eight years ago. Look at the DNA code. The DNA code is invisible, and yet the DNA code has enough information to build you an Amazon rainforest, or build a hundred David Browns. I mean it’s there. The point is certainly obvious. We’ve now learned that the atom is not just a bunch of billiard balls going around Bohr’s solar system. The atom, we have every reason to expect, is charged with enormous miniaturized information. . .

David: What have you gained from your illness, and how has the dying process affected you?

Timothy: When I discovered that I was terminally ill I was thrilled, because I thought, “Now the real game of life begins. Oh boy! It’s the Super Bowl!” I entered into the real challenge of how to live an empowered life, a life of dignity. How you die is the most important thing you ever do. It’s the exit, the final scene of the glorious epic of your life. Death is loaded with paradox and taboo, so it’s hard for me to be thinking this through, even though I’m involved in the process of dying full-time. Do you follow my confusion? I can not exaggerate the power of this taboo about dying. It’s spooky, it’s something we’re supposed to be frightened of. Death is something symbolized by Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

David: What has been the secret, all these years, to your undying sense of courage and optimism?

Timothy: It’s common sense. It’s all common sense and fair play. See, because fair play is common sense. It’s a very obvious approach to life.

My interviews with Tim appear in my book “Mavericks of the Mind,” which also contains my interview with Carolyn.