Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

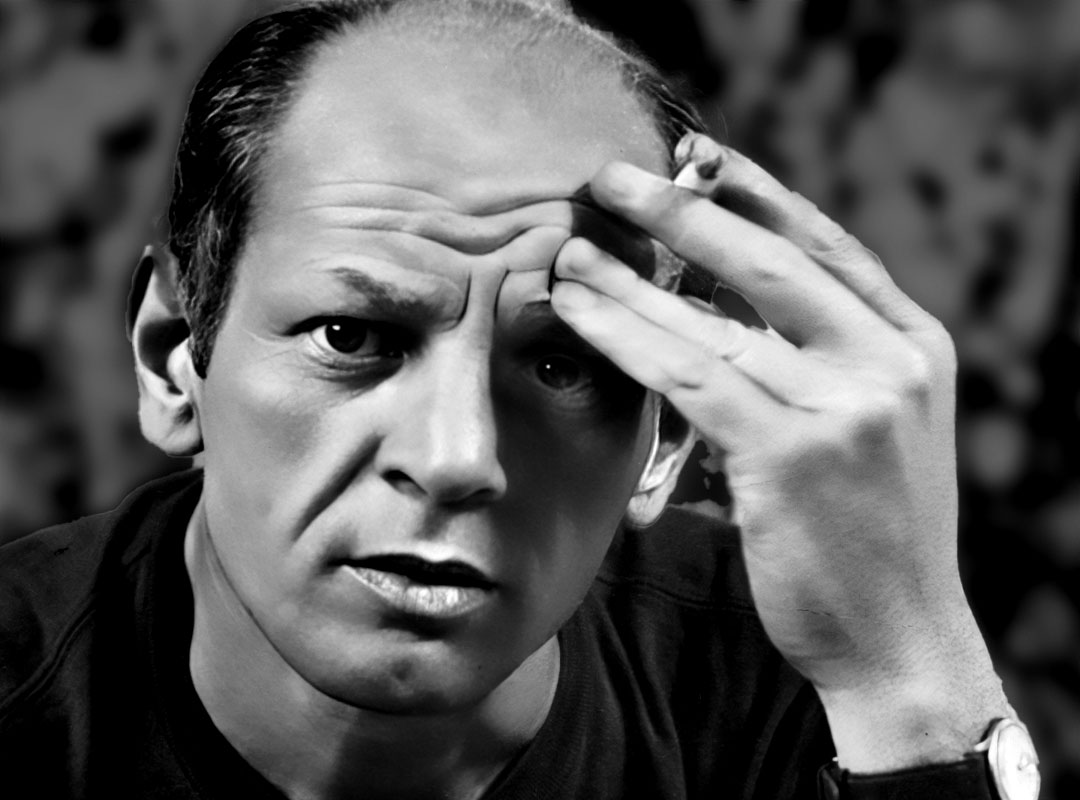

Carolyn and I have admired the work of American painter Jackson Pollock, who was a leading figure in the abstract expressionism art movement, which was characterized by freely associative painting styles that helped the art world to redefine what a painting could be. Pollock is most well-known for developing the “drip technique,” a painting method that involves dripping, pouring, or splashing paint onto a horizontal surface, enabling the artist to paint his or her canvas from multiple angles. Pollock’s revolutionary work influenced many subsequent art movements that followed abstract expressionism.

Paul Jackson Pollock was born in Cody, Wyoming in 1912. His father, who was of Scottish-Irish descent, was a farmer and land surveyor for the government. Pollock’s mother came from an Irish family with a heritage of weavers, and she made and sold dresses. Pollock’s family left Wyoming when he was 11 months old, and he grew up in Arizona and California. Pollock’s childhood wasn’t very stable; his family moved nine times in the next 16 years, and in 1928 Pollock was expelled from two high schools for being a “troublemaker.”

In 1928, Pollock enrolled at the Manuel Arts School in Los Angeles, where he met painter and illustrator Frederick Schwankovsky, who gave him some training in drawing and painting and encouraged his interest in metaphysical and spiritual literature. Schwankovsky was a member of the Theosophical Society and was friends with Jiddu Krishnamurti. These early spiritual explorations may have influenced Pollock, as in subsequent years he embraced the theories of Swiss psychologist Carl Jung and the notion of unconscious imagery being expressed in his painting.

In 1930, Pollock moved to New York City, where his older brother was living, and he studied drawing, painting, and composition at the Art Students League. In 1936, Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros introduced Pollock to the use of liquid paint at an experimental workshop, and he later used paint pouring as one of his painting techniques. During this time Pollock’s painting style was part of the regionalism movement that depicted realistic scenes, and his style slowly began to become more abstract.

Around this time, Pollock began drinking too much. In 1937, he began treatment for a problem with alcoholism by undergoing Jungian psychotherapy. In 1938, he suffered a nervous breakdown, which caused him to be institutionalized for about four months, and his treatment involved being engaged with his art. Pollock was encouraged to make drawings and to see Jungian concepts and archetypes expressed in his paintings, as a way of exploring his unconscious mind.

From 1938 to 1942, Pollock found work as an easel painter with the Federal Arts Project, a federal program that helped struggling artists find employment during the Great Depression. In the early 1940s, Pollock moved to Springs, New York, and began developing his “drip” technique, with his canvases laid out on the studio floor. Pollock’s technique typically involved pouring paint straight from a can or along a stick onto a canvas lying horizontally on the floor.

In 1942, Pollock met the artist Lee Krasner at a gallery exhibition. They became romantically involved, influenced one another’s art, and in 1945 the couple was married. Krasner had extensive knowledge and training in modern art, and she introduced Pollock to many collectors, critics, and other artists who would further his career.

In 1943, Pollock signed a gallery contract with Peggy Guggenheim, and he did his first wall-sized work, a huge 8-by-20-foot abstract oil painting titled Mural. The painting was commissioned for the entrance hall of Guggenheim’s townhouse in NYC. In the foreword to the exhibition catalog, a New York Times reviewer described Pollock’s creativity as “…volcanic. It has fire. It is unpredictable. It is undisciplined. It spills out of itself in a mineral prodigality, not yet crystallized.” Mural represents Pollock’s “breakthrough into a totally personal style in which compositional methods, and energetic linear invention, are fused with the Surrealist free association of motifs and unconscious imagery.”

Between 1947 and 1950 was Pollock’s “drip period,” when he produced some of his most famous abstract paintings. The process involved pouring or dripping paint onto a flat canvas in stages, often alternating weeks of painting with weeks of contemplating, before he finished a canvas. A whole series of famous paintings were created during this period, such as Full Fathom Five, Lucifer, and Summertime. Pollock also created more mural-sized canvases, such as One, Autumn Rhythm, and Lavender Mist.

In 1949, Life magazine did a four-page spread of Pollock’s work, and the accompanying article suggested that he might be the “greatest living painter” in the United States. Then, at the peak of his fame, Pollock abruptly abandoned the drip style of painting. He began attempting to balance abstraction with depictions of figures in his paintings and used darker colors.

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Pollock had one-man shows of new paintings nearly every year in New York. His work was handled by Peggy Guggenheim through 1947, then by the Betty Parsons Gallery from 1947 to 1952, and then by the Sidney Janis Gallery from 1952 onward.

After 1953, Pollock’s health began to deteriorate, and his production began to wane, but he still produced a number of important paintings in his final years, such as White Light and Scent. In 1956, Pollock died in a single-car crash while under the influence of alcohol.

Four months after his death, Pollock was given a memorial retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Pollock did not profit financially from his fame. During his lifetime, Pollock never sold a painting for more than $10,000 and was often hard-pressed for cash, but in 2016, his painting “umber 17A sold for $200 million. Now considered an “iconic” master of mid-century Modernism, his work influenced the American art movements that immediately followed Abstract Expressionism — such as Happenings, Pop Art, Op Art, and Color Field painting.

One of the things that I’ve found most intriguing about Pollock’s art is how it continues to be controversial, almost seven decades after his death. It’s not uncommon to hear people say“It’s just the flinging of paint!” This leads me to believe that Pollock’s critics, be they of his time or ours, are largely wrong — for it’s hard for me to understand why people would get so worked up over an artist, almost 70 years after his death unless there’s something in his work that truly matters.

Some of the quotes that Jackson Pollock is known for include:

Painting is self-discovery. Every good artist paints what he is.

New needs need new techniques. And the modern artists have found new ways and new means of making their statements… the modern painter cannot express this age, the airplane, the atom bomb, the radio, in the old forms of the Renaissance or of any other past culture.

On the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting.

The secret of success is… to be fully awake to everything about you.

There is no accident, just as there is no beginning and no end.

The painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through.

When I’m painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing. It’s only after a get acquainted period that I see what I’ve been about. I’ve no fears about making changes for the painting has a life of its own.

Modern artists unravel inner universes, expressing energy, motion, and latent forces.