Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

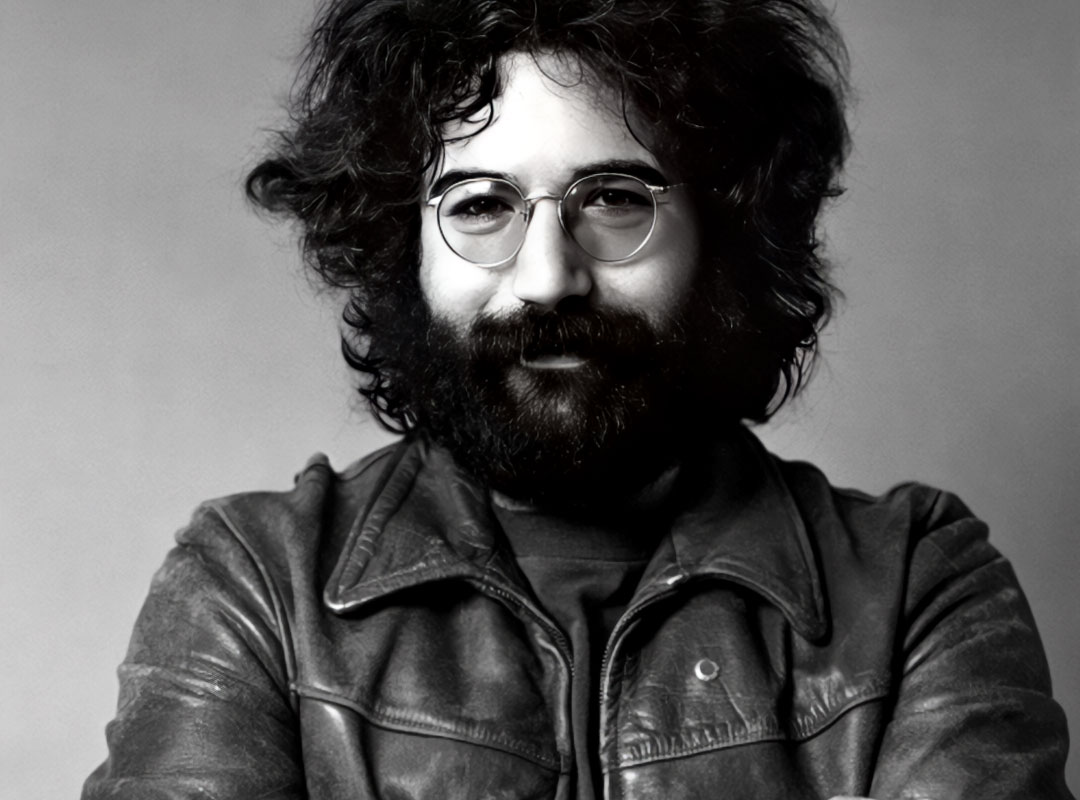

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of musician, singer, and songwriter Jerry Garcia, best known as the lead guitarist and vocalist for The Grateful Dead, one of the most influential and enduring bands in rock history. With his distinctive improvisational guitar style and eclectic musical influences— ranging from bluegrass and folk to jazz and psychedelic rock — Garcia helped pioneer the countercultural sound of the 1960s. Garcia’s live performances with The Grateful Dead became the stuff of legend, defining an era of improvisational rock and fostering an unparalleled concert experience.

Over their 30-year career, The Grateful Dead played more than 2,300 concerts, the most of any band in history at the time. Their shows drew millions of fans, with some estimates suggesting that more than 25 million people attended their concerts. Beyond The Grateful Dead Garcia collaborated on numerous side projects, including the Jerry Garcia Band, and contributed to a wide array of musical recordings. A cultural icon, Garcia’s artistry and free-spirited philosophy left an indelible mark on generations of musicians and fans.

Jerome John Garcia was born in 1942 in San Francisco, California. Both of his parents had strong ties to music and the arts. His father was a Spanish immigrant who worked as a Jazz musician and owned a tavern in San Francisco. He played woodwind instruments, particularly the clarinet and saxophone, and was part of a swing band. His mother was a native Californian who took over managing the family tavern after her husband died in 1947. She was independent and strong-willed, later working as a nurse. His mother also had a deep appreciation for music, which she passed down to Jerry, encouraging his artistic interests from a young age.

Garcia’s father drowned while fishing when Garcia was only five, leaving his mother to raise him and his older brother. That same year, Garcia suffered another life-altering event when he accidentally lost two-thirds of his right middle finger in a wood-chopping accident in the Santa Cruz Mountains, an injury that would later shape his distinctive guitar-playing style. Despite these hardships, his early years were filled with artistic and musical exposure, as his mother encouraged his creativity, and he developed an early love for the guitar.

As a child, Garcia was artistic, imaginative, and somewhat rebellious. He had a deep love for drawing and storytelling, often spending hours sketching and immersing himself in comic books and science fiction. Despite his early exposure to music, he initially showed more interest in visual arts than in playing instruments. He was also known for his mischievous streak, sometimes getting into trouble at school and struggling with authority. Garcia adapted quickly to losing part of his finger and didn’t let it hinder his creativity. His mother described him as a dreamer, and even as a young boy, he had an unconventional, free-spirited nature that foreshadowed his future as a countercultural icon.

Garcia was largely raised by his grandparents and older brother. In 1950, his mother enrolled him in an art school, nurturing his passion for drawing and creativity. However, Garcia was a restless and rebellious student, often struggling in structured environments. In 1953, at the age of 11, his mother moved the family to Menlo Park, California, where he was first introduced to rhythm and blues and early rock ‘n’ roll through the radio and his older brother’s record collection. Around this time, he also started experimenting with the banjo and guitar, marking the beginning of his lifelong relationship with stringed instruments.

In 1957, Garcia’s older brother introduced him to rock and roll, sparking his love for the electric guitar. Around this time, he discovered Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley, whose music greatly influenced his playing style. In 1959, Garcia dropped out of high school and briefly attended the San Francisco Art Institute before joining the U.S. Army— though his rebellious nature led to a discharge after just nine months. After leaving the military in 1960, he drifted through Northern California, living a bohemian lifestyle and immersing himself in folk and bluegrass music.

A major turning point came in 1961 when a near-fatal car accident left him determined to dedicate his life to music. Garcia and several friends were driving through the Santa Cruz Mountains when the driver lost control, causing the car to flip. One of his friends died in the crash, but Garcia miraculously survived. Shaken by the experience, he later described it as a “wake-up call,” realizing that he wanted to dedicate his life to playing music rather than drifting aimlessly. This pivotal moment set him on the path toward becoming one of the most legendary musicians of all time. That same year, he met Robert Hunter, his future songwriting partner, and he began performing in coffeehouses.

Garcia began playing bluegrass and folk music in the Palo Alto area, forming the band Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions with Ron “Pigpen” McKernan and Bob Weir. By 1965, inspired by the rising psychedelic movement, the group evolved into The Warlocks and was later renamed The Grateful Dead. By 1966, The Grateful Dead became central to author Ken Kesey’s legendary Acid Tests, blending psychedelic rock with improvisational jamming in environments where psychedelics were consumed.

Psychedelics played a profound role in shaping Garcia’s creativity, philosophy, and musical approach. His early experiences with LSD expanded his perception of reality and deeply influenced his improvisational style, allowing him to approach music as a fluid, ever-evolving conversation. Psychedelics also reinforced his free-spirited philosophy, emphasizing the importance of play, spontaneity, and interconnectedness, both in life and on stage. He saw The Grateful Dead performances as shared psychedelic experiences, where music became a vehicle for exploration, transformation, and collective consciousness.

As the San Francisco counterculture movement flourished, The Grateful Deadsigned with Warner Bros. Records and released their self-titled debut album in 1967. Their live performances, particularly at events like the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, solidified their reputation as pioneers of psychedelic rock. By 1968, they were expanding their musical range, incorporating jazz and experimental elements.

The Grateful Deadwas known for its extended, free-flowing jams, unpredictable setlists, and deep connection with its audience, earning a devoted fanbase known as Deadheads. The band’s ability to create a unique, ephemeral musical experience at every show made their live performances an essential part of their legacy. In 1969, Garcia and The Grateful Dead performed at Woodstock, further cementing their role in the counterculture movement. That same year, they released Live/Dead, their first live album, which captured their legendary improvisational style. In 1970, they reached new heights with the release of Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty, albums that introduced a folk and country influence, including classics like Truckin’ and Casey Jones.

Throughout the early ’70s, Garcia also explored side projects, forming the Jerry Garcia Band and collaborating with other musicians. By 1972, after the passing of founding member Pigpen, the band continued evolving musically, culminating in their 1972 European tour and live album. In 1973, they released Wake of the Flood, the first album on their independent label, Grateful Dead Records. However, in 1974, the band temporarily took a break from touring, partly due to the physical and financial toll of their massive Wall of Sound speaker system experiment. Despite this, Garcia remained musically active, releasing solo albums and continuing to refine his eclectic style before The Grateful Deadreturned in 1976.

In 1971, our friend psychologist Stanley Krippner conducted a telepathy experiment at a Grateful Dead concert at the Capitol Theatre in Port Chester, New York. The experiment aimed to test whether telepathic communication could occur between the band’s audience and a designated “receiver” in a sleep lab. While the Grateful Dead played, members of the audience were shown a series of randomly selected images on a screen and were instructed to mentally “send” these images to a sleeping subject at the Maimonides Medical Center Dream Laboratory in Brooklyn. Later, when the receiver’s dreams were analyzed, some notable correspondences emerged between the dream imagery and the projected pictures, suggesting possible extrasensory perception. Though not conclusive, the study remains one of the most fascinating intersections of parapsychology, music, and consciousness research, reflecting both Krippner’s and the Grateful Dead’s interest in mind expansion and the nature of reality.

In 1976, Garcia and The Grateful Dead resumed touring with a refined, jazz-influenced sound, and in 1977, they released Terrapin Station, featuring the epic title track that became a fan favorite. The late ’70s saw some of their most acclaimed live performances. During this period, Garcia also expanded his solo work, releasing Cats Under the Stars in 1978 with the Jerry Garcia Band, which he later called his favorite personal project. However, by the early 1980s, Garcia’s heroin addiction and declining health began affecting his performance.

In 1986, Garcia fell into a diabetic coma, nearly dying. After awakening, he had to relearn how to play the guitar, but the experience revitalized his passion for music. By 1987, The Grateful Deadexperienced an unexpected commercial breakthrough with In the Dark, which featured the song Touch of Grey, their only Top 10 hit. The album’s success introduced the band to a new generation of fans, leading to sold-out stadium tours.

The Grateful Dead remained one of the highest-grossing touring acts, playing massive stadium shows and embracing new technology, including MIDI guitars to expand their sound. Garcia also rekindled his love for acoustic music, collaborating with David Grisman on several projects. However, his health deteriorated due to diabetes, weight gain, and ongoing substance abuse. In 1992, Garcia was hospitalized and forced to take a break from touring, but he returned the following year despite continuing struggles. As his health struggles intensified, Garcia’s outlook on life and music remained deeply influenced by his spiritual philosophy, which had long been intertwined with his artistic journey.

Garcia had a fluid and open-ended spiritual perspective, shaped by psychedelics, Eastern philosophy, and the countercultural ethos of the 1960s. He was fascinated by mysticism, the nature of consciousness, and the interconnectedness of all things, often expressing a belief in cosmic playfulness and improvisation as guiding forces in life and music. Though he wasn’t formally religious, he was deeply influenced by Buddhism, the Tao Te Ching, and the transcendental aspects of Grateful Dead performances, which he saw as a kind of collective spiritual experience shared with the audience.

Garcia’s health continued to decline, but despite this, he toured with The Grateful Dead through the summer, though his performances were often frail and inconsistent. Seeking recovery, Garcia checked into the Serenity Knolls treatment center in Forest Knolls, California, in 1995. Just days after entering rehab, he passed away in his sleep from a heart attack at the age of 53.

Garcia’s legacy extends far beyond his role as The Grateful Dead’s frontman— he became a cultural icon, embodying the spirit of musical exploration and countercultural freedom. His improvisational guitar style and genre-blending approach influenced countless musicians, while his work with The Grateful Dead helped pioneer the modern jam band movement. Beyond music, he left an impact through his artwork, humanitarian efforts, and the enduring community of Deadheads who continue to celebrate his music. Even after his passing, his influence remains alive through tribute bands, festivals, and a continued appreciation for his visionary approach to sound and storytelling.

The Grateful Dead released a total of 13 studio albums and 10 live albums during their active years, along with numerous archival releases after Garcia’s passing. While their studio albums were well-received, it was their live recordings that truly captured the essence of their improvisational spirit and kept their fanbase engaged. Commercially, The Grateful Dead achieved gold and platinum status multiple times, and the band’s total album sales exceeded 35 million worldwide.

I attended two live Grateful Dead shows in the late 1980s, and one performance of the Jerry Garcia Band. In 1993, Jerry wrote a quote for the back cover of my book Mavericks of the Mind (which was recently published in its third edition and contains an interview with Carolyn). In 1994, I interviewed Jerry for my book Voices from the Edge. It was an amazing experience for Rebecca Novick and me to have 3 hours alone with Jerry after we overheard his publicist turning down an interview with Rolling Stone magazine because he was too busy. I see our interview referenced in many books about Jerry because I think we were among the few interviewers to ask him questions outside of music, like about his near-death experience, God, psychic phenomena, and synchronicity. Here are some excerpts from our conversation:

David: Joseph Campbell, the renowned mythologist, attended a number of your shows. What was his take?

Jerry: He loved it. For him, it was the bliss he’d been looking for. “This is the antidote to the atom bomb,” he said at one time.

David: He also described it as a modern-day shamanic ritual, and I’m wondering what your thoughts are about the association between music, consciousness, and shamanism.

Jerry: If you can call drumming music, music has always been a part of it. It’s one of the things that music can do— it can transport. That’s what music should do at its best— it should be a transforming experience. The finest, the highest, the best music has that quality of transporting you to other levels of consciousness.

David: I’m curious about how psychedelics influenced not only your music but your whole philosophy of life.

Jerry: Psychedelics were probably the single most significant experience in my life. Otherwise, I think I would be going along believing that this visible reality here is all that there is. Psychedelics didn’t give me any answers. What I have are a lot of questions. One thing I’m certain of; the mind is incredible and there are levels of organizations of consciousness that are way beyond what people are fooling with in day-to-day reality.

David: How did psychedelics influence your music before and after?

Jerry: Phew! I can’t answer that. There was a me before psychedelics and a me after psychedelics, that’s the best I can say. I can’t say that it affected the music specifically, it affected the whole me. The problem of playing music is essentially of muscular development and that is something you have to put in the hours to achieve no matter what. There isn’t something that strikes you and suddenly you can play music.

David: You’re talking about learning the technique, but what about the inspiration behind the technique?

Jerry: I think that psychedelics was part of music for me in so far as I’m a person who was looking for something and psychedelics and music are both part of what I was looking for. They fit together, although one didn’t cause the other.

David: What’s your concept of God if you have one?

Jerry: I was raised a Catholic so it’s very hard for me to get out of that way of thinking. Fundamentally I’m a Christian in that I believe that to love your enemy is a good idea somehow. Also, I feel that I’m enclosed within a Christian framework so huge that I don’t believe it’s possible to escape it, it’s so much a part of the Western point of view. So I admit it, and I also believe that real Christianity is okay. I just don’t like the exclusivity clause. But as far as God goes, I think that there is a higher order of intelligence something along the lines of whatever it is that makes the DNA work. Whatever it is that keeps our bodies functioning and our cells changing, the organizing principle— whatever it is that created all these wonderful life forms that we’re surrounded by in its incredible detail.

There’s a huge vast wisdom of some kind at work here. Whether it’s personal— whether there’s a point of view in there, or whether we’re the point of view, I think is up for discussion. I don’t believe in a supernatural being…. I’ve been spoken to by a higher order of intelligence— I thought it was God. It was a very personal God in that it had the same sense of humor that I have. I interpret that as being the next level of consciousness, but maybe there’s a hierarchical set of consciousnesses. My experience is that there is one smarter than me, that can talk to me, and there’s also the biological one that I spoke about.