Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

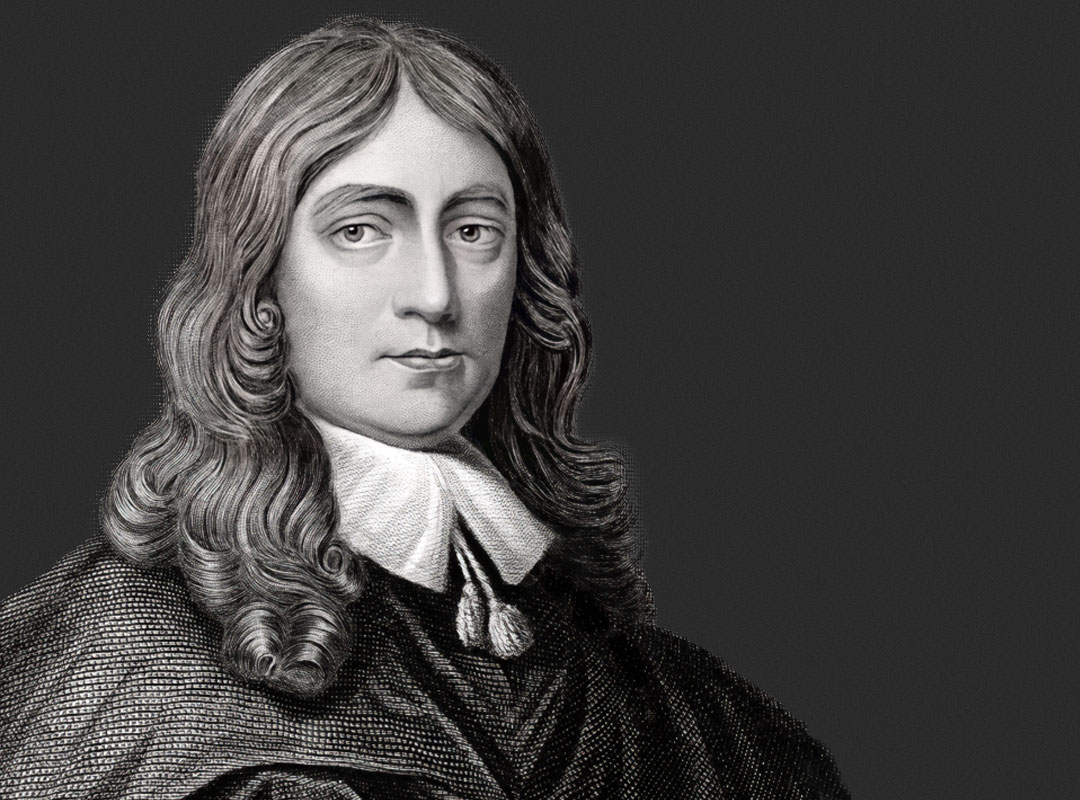

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of English writer John Milton, who is considered one of history’s greatest poets. Milton is best known for his epic poem Paradise Lost, which masterfully explores the biblical story of humanity’s fall from grace, combining profound theological insights with extraordinary poetic artistry— and is considered one of the greatest works in the English language.

Beyond his literary achievements, Milton was a staunch advocate for individual liberty, free speech, and press freedom. Despite going blind in midlife, he continued to write, dictating his later works, and he remains celebrated as one of the most influential English poets and thinkers of all time. According to some scholars, Milton is second in influence only to William Shakespeare.

John Milton was born in 1608 in London, England, into a prosperous and educated family. His father was a scrivener, which involved drafting legal documents and providing financial services. He was also an accomplished composer of church music, contributing to Milton’s early exposure to the arts. His mother managed the household and cared for the family, offering a stable and nurturing environment. His family’s financial stability and commitment to education provided the foundation for his later achievements.

As a child, Milton was precocious, highly intelligent, and deeply curious. He received a privileged early education, learning Latin and Greek, and he displayed exceptional intellectual promise as a child, particularly excelling in languages. His father’s encouragement and access to a private tutor fostered his intellectual development. Known for his discipline and dedication to study, Milton often stayed up late reading by candlelight.

Milton attended St. Paul’s School in London, where he received a rigorous classical education, studying the foundations of rhetoric and poetry. Milton’s intellectual brilliance became evident as he immersed himself in literature and language, preparing for a scholarly life. These formative years also saw his deepening interest in religion and the arts, largely influenced by his father’s musical talents and Puritan faith, which would later shape his literary voice and worldview.

In 1625, Milton enrolled at Christ’s College, University of Cambridge. During this period, he began developing his poetic talents, and writing his earliest known works. Though he briefly faced disciplinary action and was temporarily suspended from Christ’s College in 1626 due to a dispute with his tutor, Milton returned to complete his studies.

In 1629, Milton completed his Bachelor of Arts degree, and in 1632 his Master of Arts at Christ’s College, further honing his linguistic and poetic skills. During this time, Milton wrote several significant early poems, including On Shakespeare in 1630, which reflected his admiration for the Bard, and On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity in 1629. After leaving Cambridge, Milton returned to his family’s home in Hammersmith and later moved to Horton, where he devoted himself to rigorous private study of classical and contemporary works.

In 1634, his masque Comus was performed at Ludlow Castle, showcasing his mastery of dramatic poetry and themes of virtue and morality. In 1637, he wrote the pastoral elegy Lycidas in memory of a Cambridge friend, which became one of his most celebrated works. Between 1638 and 1639, Milton embarked on a transformative journey across Europe, meeting intellectuals in Italy and deepening his understanding of art, philosophy, and politics.

While visiting Florence during his travels in Italy, Milton met the renowned scientist Galileo Galilei, who was under house arrest by the Inquisition for his heliocentric views — meaning that he believed that the earth and planets orbited the sun, which contradicted the church’s prevailing view of geocentrism, which placed the earth at the center of the universe. This meeting left a profound impression on Milton, and he later referred to Galileo in Paradise Lost as the “Tuscan artist” observing the heavens through his telescope. The encounter highlights Milton’s admiration for intellectual courage and scientific inquiry, themes that permeated his works.

Around this time Milton became deeply involved in political and religious debates, setting aside poetry to write a series of influential prose works. He published tracts advocating for religious reform, such as Of Reformation in 1641 and The Reason of Church-Government in 1642, aligning himself with Puritan ideals. In 1643, Milton married Mary Powell, but the marriage was temporary, and she returned to her family, prompting Milton to write treatises advocating for divorce rights, including The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce. During this period, Milton also became a teacher, running a small school for his nephews and other students.

In 1651, as the English Civil War concluded and the monarchy was overthrown, Milton became a staunch supporter of the Commonwealth, a political community founded for the common good. In 1649, he was appointed Secretary for Foreign Tongues to the Council of State, serving as a propagandist for the new government and writing defenses of republicanism, including The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates. During this time, he penned his famous works defending the execution of King Charles I and refuting royalist arguments.

Around this time, Milton’s health started to deteriorate, and by 1652, he became completely blind, likely due to glaucoma or retinal detachment, conditions exacerbated by his intense study habits and the strain of writing and reading late into the night. Despite this, Milton continued his intellectual pursuits, dictating his writings and laying the groundwork for his later masterpieces. In 1659, Milton dictated A Treatise of Civil Power, advocating for religious liberty.

The restoration of the monarchy in 1660 marked a dangerous period for Milton as a prominent supporter of the Commonwealth. He was briefly imprisoned but later pardoned. During this time, Milton faced further personal losses, including the death of his second wife and their infant daughter.

Living a relatively quiet life in London, Milton dictated Paradise Lost, his epic masterpiece, which was published in 1667 to critical acclaim. Paradise Lost recounts the biblical story of humanity’s fall, exploring the rebellion of Satan, the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden, and themes of free will, redemption, and divine justice. The poem solidified Milton’s reputation as one of the greatest poets in the English language. During this time, he also married his third wife, who supported him in his later years. Milton continued writing, beginning work on Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes, which further explored themes of faith, redemption, spiritual triumph, and human resilience.

Milton’s spiritual perspective was deeply rooted in his Christian faith, influenced by Puritanism and his belief in individual conscience. He emphasized humanity’s direct relationship with God, advocating for personal responsibility and moral choice. His works reflect his view of God as just and sovereign, yet also compassionate, and explore themes of free will, redemption, and divine grace. Milton rejected institutionalized religion, critiquing the corruption of the Church and championing religious liberty. His writings, particularly Paradise Lost, grapple with profound spiritual questions about good, evil, and humanity’s purpose within God’s divine plan.

In 1671, Milton published Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes, and the publication of these works further cemented his status as one of the greatest English poets. Despite declining health, Milton continued to write and engage in intellectual discussions. In the final year of his life, he oversaw the publication of the second edition of Paradise Lost, which included explanatory notes and a commendatory poem by Andrew Marvell, solidifying its growing reputation. Milton lived quietly in London with his third wife and continued to receive visitors and admirers.

Milton passed away peacefully in 1674, at the age of 65, leaving an unparalleled legacy as one of England’s greatest poets and thinkers. His legacy lies in his profound contributions to literature, theology, and political thought. His epic poems and political prose showcase his mastery of language, depth of thought, and commitment to liberty and individual rights. Milton’s influence extends beyond poetry, shaping discussions on freedom of speech, religion, and the human condition. His blend of artistic genius and intellectual rigor continues to inspire writers, scholars, and readers worldwide.

Milton was revered by William Blake, William Woodsworth, and many other poets and artists. Blake created several sets of illustrations for Paradise Lost. His illustrations are renowned for their vivid symbolism and dynamic compositions, capturing the epic poem’s profound themes and complex characters. Blake’s unique artistic style brought a visionary interpretation to Milton’s work, influencing subsequent generations of artists and readers.

Some of the quotes that John Milton is known for include:

The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven.

Solitude sometimes is best society.

Long is the way and hard, that out of Hell leads up to light.

Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties.

What is dark within me, illumine.

A good book is the precious life-blood of a master spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life.

Thou canst not touch the freedom of my mind.

Yet he who reigns within himself, and rules

Passions, desires, and fears, is more a king.

For books are not absolutely dead things, but do contain a potency of life in them to be as active as that soul was whose progeny they are; nay, they do preserve as in a vial the purest efficacy and extraction of that living intellect that bred them.