Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

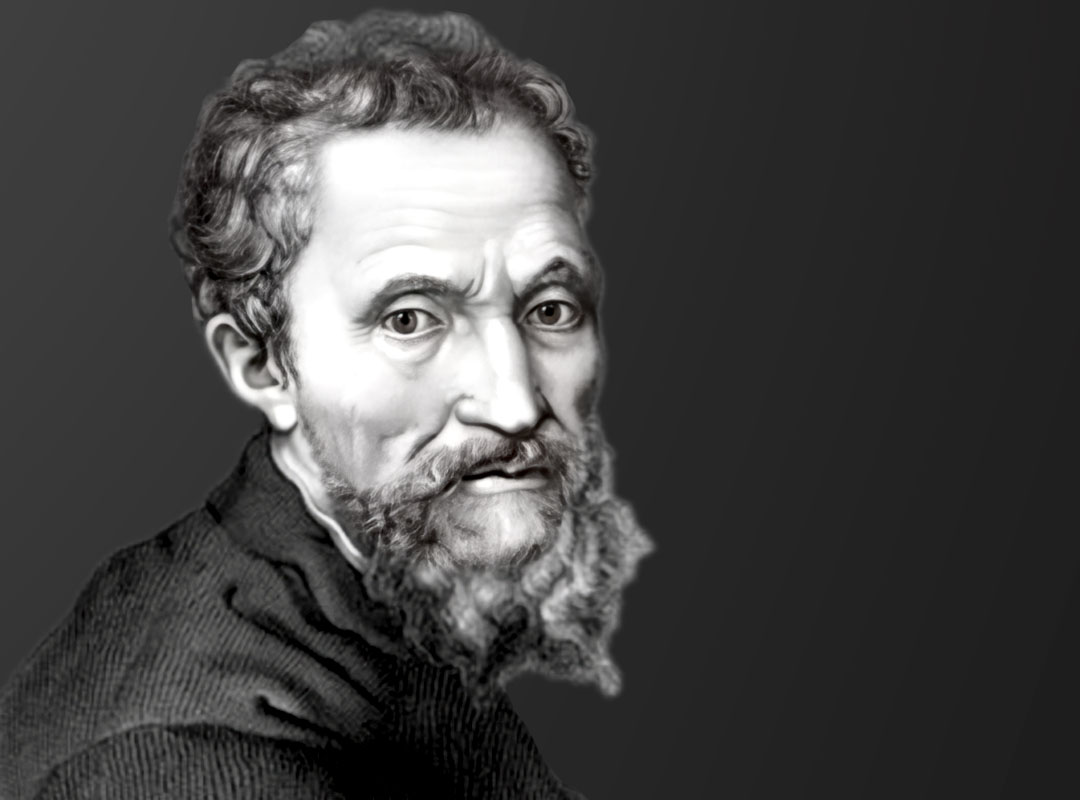

Carolyn and I have long admired the work of Michelangelo — Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet — who was a towering figure of the Renaissance and is celebrated as one of history’s greatest artists. Renowned for his masterful sculptures, David and Pietà, he also painted the awe-inspiring ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, which remains one of the crowning achievements of Western art. Michelangelo helped shape the course of art and architecture for centuries, notably designing the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. His genius left an indelible mark on the world, merging divine beauty with human form. With renewed global attention on the Vatican following the election of the new pope, Michelangelo’s enduring presence in St. Peter’s Basilica and the Sistine Chapel reminds us of how deeply his art continues to shape the spiritual and cultural heart of the Catholic world.

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni was born in 1475 in Caprese, a small town within the Republic of Florence — a powerful medieval and early modern state whose capital was the city of Florence, in Tuscany, Italy. Michelangelo’s father was a minor Florentine official from a once-prominent but declining noble family. He held occasional government posts, such as magistrate or local administrator, but struggled financially and never achieved lasting success. His mother came from a similarly respectable background but died when Michelangelo was six years old. Despite their noble lineage, Michelangelo’s parents were not wealthy, and his father initially disapproved of his artistic ambitions, viewing them as beneath the family’s social standing.

After Michelangelo’s mother became ill and died, he was sent to live with a wet nurse in the nearby town of Settignano, where her family worked as stonecutters. Growing up in this environment, surrounded by marble and chisels, likely planted the earliest seeds of his sculptural genius. As a child, Michelangelo was sensitive, intelligent, and deeply drawn to art, often preferring sketching and observing nature over traditional studies. He was known to be somewhat aloof and introspective, with a fierce independence and strong will that sometimes clashed with his family’s expectations. Even at a young age, he displayed remarkable artistic talent, and by the time he was a teenager, his skills in drawing and sculpture were apparent.

During the early 1480s, Michelangelo attended the Latin school of Francesco da Urbino, though he showed little interest in traditional education. Instead, he spent much time copying drawings and visiting churches to study frescoes. In 1487, at just twelve years old, he was apprenticed to the painter Domenico Ghirlandaio, marking the official beginning of his artistic training in one of Florence’s leading workshops.

After a brief apprenticeship with Ghirlandaio, Michelangelo was recommended to the Medici family and, by 1490, was studying at the Medici-sponsored sculpture garden under the guidance of Bertoldo di Giovanni. There, he gained exposure to classical antiquities and mingled with Florence’s intellectual elite, including Lorenzo de’ Medici, who became his patron. During this time, Michelangelo sculpted some of his early masterpieces, such as the Battle of the Centaurs. However, after Lorenzo died in 1492 and rising political unrest in Florence, Michelangelo left the Medici court. By 1494, with tensions escalating under Savonarola’s influence, he departed Florence for Bologna, seeking refuge and continuing his artistic development.

In 1496, at just 21 years old, Michelangelo sculpted a marble Cupid and, at the suggestion of a dealer, artificially aged it to appear ancient. The sculpture was sold to Cardinal Riario of San Giorgio in Rome, who later discovered the deception. Rather than being outraged, the Cardinal was so impressed by Michelangelo’s skill that he invited the young artist to Rome — an invitation that launched his rise to fame.

Michelangelo traveled to Rome, where he created the Bacchus, a sensuous marble statue that impressed Roman patrons. His breakthrough came in 1498 when he was commissioned to sculpt the Pietà for St. Peter’s Basilica — an extraordinary work that blended delicate emotion with technical brilliance. In 1501, Michelangelo returned to Florence and received the commission for what would become one of his most iconic masterpieces: the colossal marble statue of David, which was completed in 1504 and instantly hailed as a symbol of civic pride and artistic genius.

Michelangelo then began work on the Battle of Cascina fresco, though it remained unfinished. In 1505, Pope Julius II summoned him to Rome to design a grandiose tomb, a project plagued by delays and complications. Tensions with the Pope led Michelangelo to briefly flee Rome, but in 1508 he was called back — this time to begin one of the most ambitious artistic feats in history: painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, the large papal chapel built within the Vatican between 1477 and 1480.

Michelangelo became immersed in the monumental task of painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling, a commission that would define his legacy. Working largely alone under grueling conditions, he completed the frescoes in 1512, unveiling a breathtaking vision of biblical scenes — from the Creation of Adam to the prophets and sibyls — that stunned the world and redefined Renaissance art. Following this triumph, he returned briefly to work on Pope Julius II’s tomb and created the powerful Moses statue.

In 1513, after Julius’s death, Pope Leo X, a member of the powerful Medici family, known for their wealth and patronage of the arts, came to power, and Michelangelo shifted focus to new architectural and sculptural projects. Under the patronage of the new pope, Michelangelo was tasked with designing the façade of the Church of San Lorenzo, but despite years of planning and sourcing marble from the quarries at Carrara, the project was ultimately abandoned due to funding and political complications. During this time, he also began work on the Medici Chapel, intended as a grand mausoleum for his patrons. Though progress was slow and frequently interrupted, this period marked a deepening of his architectural vision and further solidified his role as both a sculptor and architect of major importance.

Michelangelo worked intensively on the Medici Chapel in Florence, crafting striking tomb sculptures like Night and Day and Dawn and Dusk, which blended spiritual symbolism with anatomical mastery. In 1527, political upheaval shook Florence when the Medici were temporarily overthrown and the city became a republic. Michelangelo, a supporter of the republic, was appointed chief of fortifications and oversaw the city’s defenses against the impending siege by Medici and imperial forces. This marked a rare period where the artist became directly involved in military engineering, blending creativity with civic duty during a time of political crisis.

After the fall of the Florentine Republic in 1530 and the return of Medici rule, Michelangelo was briefly out of favor and feared retribution for his role in defending the republic. However, thanks to powerful allies and his immense reputation, he was pardoned and allowed to continue his work. He resumed and advanced the Medici Chapel and also began work on the Laurentian Library, designing its striking staircase and innovative architectural features. During this period, Michelangelo’s artistic focus began shifting increasingly toward architecture, and his work grew more spiritually introspective and monumental in tone.

Michelangelo held a deeply personal and evolving spiritual perspective, rooted in his Catholic faith yet infused with a profound sense of inner struggle and longing for divine truth. He believed that art was a path to God, a sacred act of revealing the divine through the beauty of the human form. In his later years, his work and poetry became increasingly contemplative, expressing remorse, humility, and a yearning for spiritual salvation. For Michelangelo, the creative act was both a gift from God and a form of worship— a means of sculpting the soul toward grace.

Michelangelo deepened his work in both sculpture and architecture while continuing to navigate shifting political and religious tides. He remained in Florence for part of this time, refining the Medici Chapel and Laurentian Library, though progress was slow due to interruptions and conflicts. In 1534, following the death of his beloved friend and muse Vittoria Colonna and amid growing tensions in Florence, Michelangelo left the city for good and settled permanently in Rome. There, Pope Paul III commissioned him to paint The Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel — a vast and emotionally charged fresco that he began in 1536 and completed in 1541, unveiling a work of awe, fear, and divine reckoning that stunned the world and cemented his spiritual and artistic legacy.

During the late 1540s, Michelangelo’s focus shifted increasingly toward architecture and religious devotion. He continued working under Pope Paul III and was appointed chief architect of St. Peter’s Basilica in 1546, a role he accepted reluctantly but would hold for the rest of his life. Michelangelo reimagined the basilica’s design with bold, unified forms, laying the groundwork for its majestic dome. During this time, he also worked on the Capitoline Hill redesign and created deeply personal sculptures like the Florentine Pietà, reflecting his preoccupation with mortality and faith in his later years.

During the 1550s, Michelangelo remained in Rome, dedicating himself almost entirely to architecture and religious art in his final decades. He continued refining the design and construction of St. Peter’s Basilica, focusing on the great dome and simplifying the plans to emphasize harmony and grandeur. He also worked on the Porta Pia and the Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri, transforming ancient Roman ruins into a Christian church. Despite his age, he remained fiercely productive, driven by spiritual conviction, and developed increasingly abstract and emotionally intense sculptural works, many of which he never completed. These years reflect a period of profound introspection and enduring creative power.

During the early 1560s, Michelangelo, now in his 80s, continued to work with remarkable dedication, primarily overseeing the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. He devoted himself to perfecting the design of its massive dome, which would become one of the most iconic architectural achievements in history. During these years, his art grew increasingly introspective and spiritual, as seen in his unfinished sculptures like the Rondanini Pietà, a raw and poignant reflection on suffering and mortality. Though he rarely left his home, Michelangelo remained an influential cultural figure, corresponding with artists and thinkers, and in 1563, he was named honorary president of the newly founded Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence, recognizing his unparalleled contributions to art and architecture.

In the final year of his life, Michelangelo remained mentally sharp and spiritually reflective. He continued to advise on the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica until just days before his death, and worked intermittently on the Rondanini Pietà. Michelangelo died in 1564, at the age of 88, in Rome. Honoring his wishes, his body was secretly transported to Florence, where he was buried with great ceremony at the Basilica of Santa Croce. Revered as a divine genius even in his lifetime, Michelangelo’s death marked the end of an era, but his legacy would shape Western art for centuries to come.

Michelangelo’s legacy is that of a visionary who redefined the boundaries of art, architecture, and human creativity. His masterpieces — such as David, the Pietà, the Sistine Chapel ceiling, and the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica— remain among the most celebrated works in Western history, exemplifying both technical brilliance and profound emotional depth. As a sculptor, painter, architect, and poet, he embodied the Renaissance ideal of the universal genius, and his influence echoes through centuries of artists who followed. Michelangelo’s work continues to inspire awe, not only for its beauty and skill, but for its spiritual intensity and enduring quest to capture the divine within the human form.

Some of the quotes that Michelangelo is known for include:

If people knew how hard I had to work to gain my mastery, it would not seem so wonderful at all.

The greatest danger for most of us is not that our aim is too high and we miss it, but that it is too low and we reach it.

If you knew how much work went into it, you wouldn’t call it genius.

Genius is eternal patience.

I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.

The sculpture is already complete within the marble block, before I start my work. It is already there, I just have to chisel away the superfluous material.

Lord, grant that I may always desire more than I accomplish.

Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.

The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection.