Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

Carolyn and I admire and appreciate the work of poet and environmentalist Robinson Jeffers, who is known for his poetry about our beloved Central California Coast.

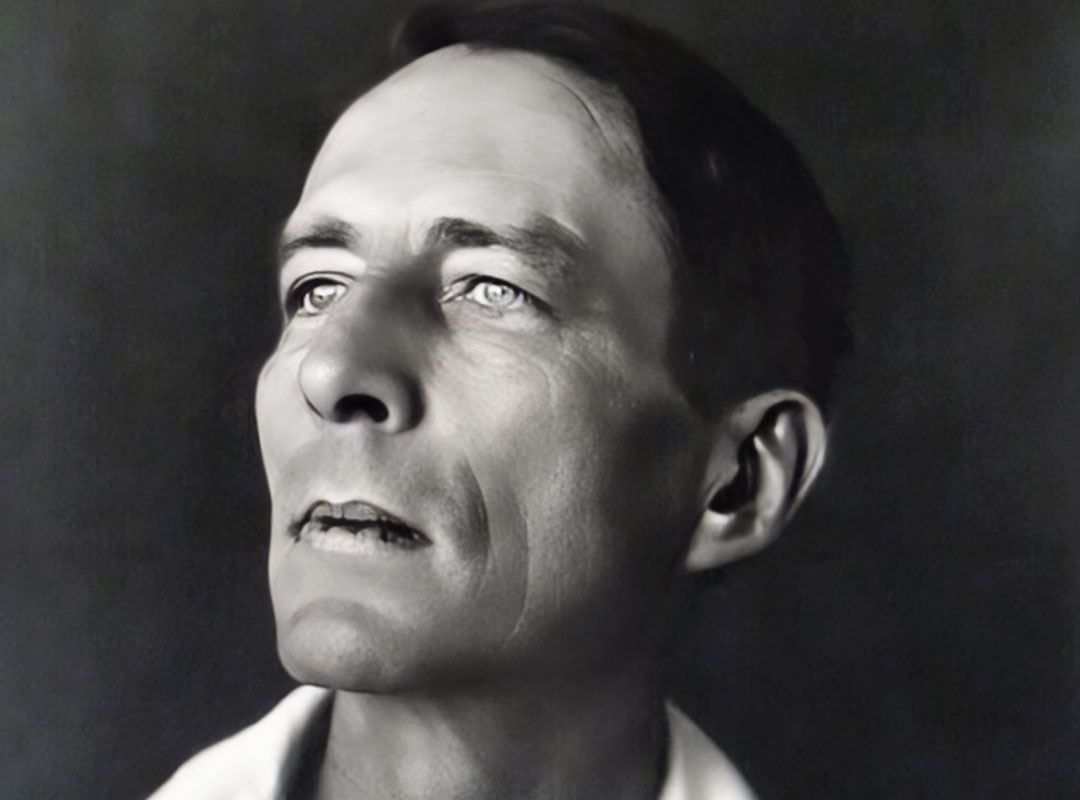

John Robinson Jeffers was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania in 1887. His father was a Presbyterian minister, his mother a Biblical scholar, and his brother became a well-known astronomer. As a child, Jeffers studied the Bible and classical languages. During his youth, he traveled through Europe and attended school in France, Germany, and Switzerland. By the time he was 12, Jeffers was fluent in French, German, and English, and he had a good knowledge of Latin and Greek.

When he was 18, Jeffers earned his degree from Occidental College in California and then studied literature at the University of Southern California as a graduate student. Jeffers then studied medicine at USC for three years, although he dropped out of medical school, and then enrolled as a forestry student at the University of Washington in Seattle, a course of study that he also abandoned after just one semester.

Jeffers returned to Los Angeles. In 1906, he met Una Kuster, a fellow graduate student, who was married at the time to a well-known attorney, and they had a passionate love affair— that became a huge scandal, reaching the front page of the Los Angeles Times. In 1912, Jeffers published his first book of poetry, Flagons and Apples, although it didn’t receive much attention. When Una got divorced in 1913, she married Jeffers the next day, and they moved to Carmel, California together.

In 1919 Jeffers built a granite house in Carmel with his own hands, named Tor House, later, he added a large four-story stone tower on the site called Hawk Tower. This became Jeffers’ family home until the end of his life. It was a magnificent and impressive accomplishment. Stewart Brand, the founder of The Whole Earth Catalog, described the Tor House as “a poem-like masterpiece” with “more direct intelligence per square inch than any other house in America.”

Around this time Jeffers began to exclusively write poetry, and he wrote his epic poem Tamar, which is a controversial tale about a ranch family, involving incest and violence. Tamar first appeared in Jeffers’ poetry collection Tamar and Other Poems, which was published in 1924. This collection brought attention to Jeffers’ work and his fame grew over the following years.

According to one account, “With the publication of Tamar and Other Poems… Jeffers’ fame sprung into being virtually overnight. One decade and multiple collections of poetry later, he had become arguably the most famous poet in the United States.” In 1932 Jeffers appeared on the cover of Time magazine. In 1946 his version of the Greek drama Medea was performed on Broadway.

In 1948 Jeffers published a poetry collection titled The Double Axe and Other Poems, which included some poems that were critical of U.S. involvement in the Second World War. The publisher censored eleven poems in the collection and included a warning that Jeffers’ views “were not those of the publishing company,” and that the book contained some potentially “unpatriotic” poems. It wasn’t until 1977 that the full collection of poems was finally published.

During the 1950s and later, as the environmental movement gained momentum, Jeffers became an important voice for protecting the natural world. He also developed a unique philosophy. Jeffers coined the term “inhumanism,” which means “the belief that humankind is too self-centered and too indifferent to the astonishing beauty of things.” Jeffers refers to this philosophy in some of his poems. For example, in his poem Carmel Point Jeffers encourages people to “uncenter” themselves.

In his poem The Double Axe, Jeffers describes “inhumanism” as “a shifting of emphasis from man to not man; the rejection of human solipsism and recognition of the transhuman magnificence. … It offers a reasonable detachment as a rule of conduct, instead of love, hate, and envy… it provides magnificence for the religious instinct, and satisfies our need to admire greatness and rejoice in beauty.” Jeffers believed that humanity had been rejected by an uncaring divine being, and that everyone should transcend emotion, and embrace an indifferent God.

Nature serves as a backdrop for much of Jeffers’ poetry. Animals and aspects of the natural world are often compared to humans, with humans being shown as inferior. Jeffers preferred nature to people, as he felt that our species failed to recognize the significance of other creatures and the natural world. His work celebrates the beauty of seas and skies, and the freedom of wild animals, and it strives to create a vision of the world in which human experience is questioned and decentered.

Although Jeffers was known to be rather reclusive, he corresponded and interacted with other notable writers and poets during his life, such as Benjamin De Casseres and D.H. Lawrence.

Jeffers died in 1962. His poems have been translated into numerous languages and published worldwide. Jeffers’ poetry has also influenced many writers, such as Gary Snyder and Charles Bukowski, who said that Jeffers was his favorite poet. In 1973 Jeffers was honored on a U.S. postage stamp.

Some of the quotes that Jeffers is known for include:

The greatest beauty is organic wholeness, the wholeness of life and things, the divine beauty of the universe.

I have heard the summer dust crying to be born.

Before there was any water there were tides of fire, both our tones flow from the older fountain.

The tides are in our veins, we still mirror the stars, life is your child, but there is in me, Older and harder than life and more impartial, the eye that watched before there was an ocean.

The beauty of things was born before eyes and sufficient to itself; the heartbreaking beauty will remain when there is no heart to break for it.

One existence, one music, one organism, one life, one God: star-fire and rock-strength, the sea’s cold flow—And man’s dark soul.

As for me, I would rather be a worm in a wild apple than a son of man. But we are what we are, and we might remember not to hate any person, for all are vicious; And not to be astonished at any evil, all are deserved; And not to fear death; it is the only way to be cleansed.

A little too abstract, a little too wise,

It is time for us to kiss the earth again,

It is time to let the leaves rain from the skies,

Let the rich life run to the roots again.