Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

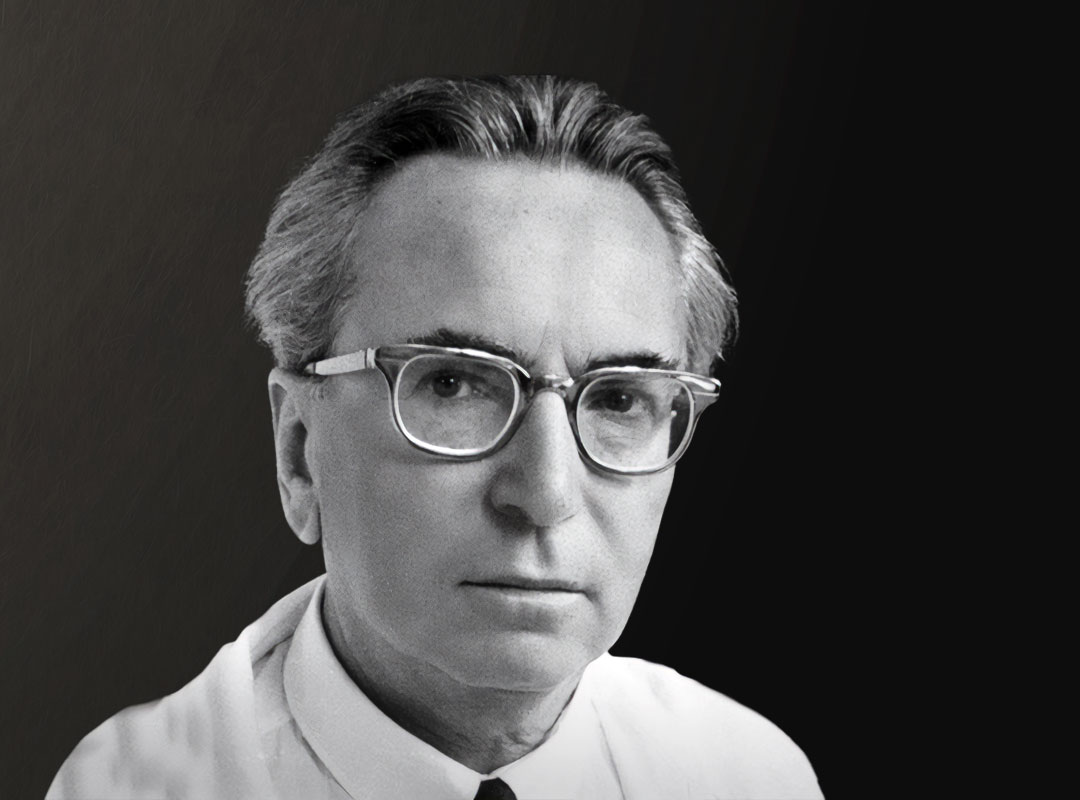

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of Austrian neurologist, psychologist, philosopher, and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl, who founded the school of existential and humanistic psychotherapy known as logotherapy, which describes a search for life’s meaning as the central human motivational force. His bestselling, autobiographical book Man’s Search for Meaning which is based on his experiences in the Nazi concentration camps, and his remarkable ability to triumph over profound tragedy, has been a powerful inspiration to millions of people.

Viktor Emil Frankl was born in 1905 in Vienna, Austria. He was born into a Jewish family and was the middle child of three children. His father was a civil servant for the Austrian government, holding positions in the Ministry of Social Service, and his mother was a homemaker. Both of Frankl’s parents were well-educated and valued learning, fostering a supportive environment for his intellectual development.

As a child, Frankl was curious, reflective, and driven by a deep desire to understand the human mind and the world around him. His family engaged in lively intellectual discussions, which fostered his early interest in philosophy and psychology.

Frankl attended a type of secondary school in Vienna known as “the Gymnasium,” where he received his early education. He attended the Wiener Wissenschaftliche Schule, a prominent academic institution. This rigorous academic environment played a significant role in shaping his intellectual development. In junior high school, Frankl began taking night classes in psychology, and as a teenager, he started a correspondence with Sigmund Freud.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 brought significant hardships to Austria, and consequently economic struggles for Frankl’s family. However, despite these challenges, Frankl excelled in school. In 1923, he graduated from high school and was accepted at the University of Vienna, where he studied medicine and focused on neurology and psychiatry. Frankl’s early interest in psychiatry was deeply influenced by Freud’s work. In 1930, he earned a Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) degree from the University of Vienna.

During this period, Frankl became involved with the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, and he shifted away from Freud’s school of thought towards Alfred Adler’s psychology, although he later distanced himself from both of these thinkers to develop his ideas. Frankl began writing and publishing on psychology and he developed an early version of his concept of “will to meaning,” which laid the groundwork for his later logotherapy.

Logotherapy is a form of existential psychotherapy that emphasizes the human search for meaning as the central motivation in life. Rather than focusing on past experiences or conflicts, logotherapy helps individuals find purpose in their present circumstances, even in suffering. It asserts that life has inherent meaning, and by discovering or creating this meaning, individuals can overcome psychological distress and find fulfillment. Frankl’s approach contrasts with Freud’s pleasure principle, as it centers on the “will to meaning” rather than the pursuit of pleasure or power.

In the early 1930s, Frankl began working with suicidal patients, particularly teens, and he ran youth counseling centers in Vienna, where his work was highly successful. Additionally, Frankl worked in various hospitals, refining his approach to treating depression and existential crises. In 1937, he opened a private practice in Vienna, specializing in neurology and psychiatry. From 1940 to 1942 Frankl was head of the Neurological Department of Rothschild Hospital. However, with the rise of Nazi Germany, Frankl faced increasing persecution for being Jewish.

Frankl decided to stay in Vienna during the Nazi occupation rather than flee to the United States. In 1941, he obtained a visa to leave Austria, but he struggled with whether to abandon his parents, who could not leave. Frankl unexpectedly found clarity— when he saw a piece of marble his father had saved from a destroyed synagogue. The marble had engraved upon it a portion of the Ten Commandments that read: “Honor your father and your mother.” This powerful moment convinced Frankl to stay with his parents in Vienna, a decision that led to his eventual deportation to the concentration camps.

In 1942, Frankl and his family were deported to the concentration camps, where most of his family, including his wife, parents, and brother were killed. Frankl was first deported to Theresienstadt in 1942, along with his family. Later, in 1944, he was transferred to Auschwitz, where he endured severe physical and profound emotional hardships. He was then moved to other camps, where he continued to struggle for survival until his liberation in 1945.

Miraculously, Frankl not only survived, but during his imprisonment, he reflected on the power of finding meaning in suffering. Remarkably, he discovered mental techniques for transcending suffering, even in the most horrific of circumstances. Throughout his time in the concentration camps, Frankl found solace in maintaining a sense of meaning and purpose, which strengthened his ideas about the power of finding meaning in even the worst situations, and this formed the basis for his logotherapy theory. After his liberation in 1945, Frankl wrote his seminal book, “Man’s Search for Meaning,” which was published in 1946, and detailed his experiences and how he triumphed over unbelievable horrors.

That same year Frankl was appointed head of the Vienna Neurological Policlinic, a position he held until 1970. In 1947, he remarried and resumed his medical and academic career, becoming a key figure in existential psychotherapy. In 1948, he earned a Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Vienna. His doctoral thesis focused on the relationship between existential philosophy and psychiatry.

In 1955, Frankl was appointed as a professor at the University of Vienna, and his ideas about meaning, purpose, and mental health were increasingly embraced in both academic and clinical circles. By 1959, his book Man’s Search for Meaning gained greater international acclaim; it was translated into multiple languages and became a key text in existential psychology. Frankl toured extensively, lecturing at prestigious universities worldwide, including Harvard University. In 1961, he also became a professor at the United States International University in San Diego.

In 1977, Frankl became a professor at the University of Dallas in Texas, and his ideas were increasingly applied in various fields, including education, philosophy, and counseling. Frankl continued lecturing extensively across Europe, the Americas, and Asia, receiving numerous honors and awards for his contributions to psychotherapy — such as the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art in 1986, recognizing his lifelong contributions — as well as honorary doctorates from various universities.

Frankl’s influence extended beyond psychology, impacting fields like education and spiritual counseling. While Frankl was not overtly religious, his views were influenced by spiritual themes, emphasizing the importance of transcending personal limitations and circumstances. Frankl believed in a dimension beyond the material, referring to a “spiritual unconscious” and often highlighting the significance of values, responsibility, and a connection to something greater than oneself. He saw spirituality as essential to psychological well-being, with logotherapy focusing on the spiritual need for meaning as a fundamental human drive.

Frankl remained active and continued to influence psychology and philosophy, and he continued to write and contribute to academic discussions on existential psychology and the human search for meaning. His health declined towards the mid-1990s, and in 1997 Frankl passed away in Vienna at the age of 92.

By the time Frankl died, his work had impacted millions worldwide. He is the author of 39 books, and in the 76 years since he first published Man’s Search for Meaning, the book has been translated into more than 50 languages and sold over 16 million copies. His insights into finding purpose under the most horrific conditions deeply resonated with general readers and professionals alike. Frankl’s legacy endures through his contributions to psychotherapy and other disciplines, as well as through his message of resilience, hope, and the importance of meaning in life.

Some of the quotes that Viktor Frankl is known for include:

Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s way.

When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.

Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how’.

An abnormal reaction to an abnormal situation is normal behavior.

No man should judge unless he asks himself in absolute honesty whether in a similar situation he might not have done the same.

What is to give light must endure burning.

For the first time in my life, I saw the truth as it is set into song by so many poets, and proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers. The truth — that Love is the ultimate and highest goal to which man can aspire. Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of man is through love and in love.

Life is never made unbearable by circumstances, but only by lack of meaning and purpose.

Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.

Forces beyond your control can take away everything you possess except one thing, your freedom to choose how you will respond to the situation.