Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

Carolyn and I have long admired the work of Michelangelo — Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet — who was a towering figure of the Renaissance and is celebrated as one of history’s greatest artists. Renowned for his masterful sculptures, David and Pietà, he also painted the awe-inspiring ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, which remains one of the crowning achievements of Western art. Michelangelo helped shape the course of art and architecture for centuries, notably designing the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. His genius left an indelible mark on the world, merging divine beauty with human form. With renewed global attention on the Vatican following the election of the new pope, Michelangelo’s enduring presence in St. Peter’s Basilica and the Sistine Chapel reminds us of how deeply his art continues to shape the spiritual and cultural heart of the Catholic world.

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni was born in 1475 in Caprese, a small town within the Republic of Florence — a powerful medieval and early modern state whose capital was the city of Florence, in Tuscany, Italy. Michelangelo’s father was a minor Florentine official from a once-prominent but declining noble family. He held occasional government posts, such as magistrate or local administrator, but struggled financially and never achieved lasting success. His mother came from a similarly respectable background but died when Michelangelo was six years old. Despite their noble lineage, Michelangelo’s parents were not wealthy, and his father initially disapproved of his artistic ambitions, viewing them as beneath the family’s social standing.

After Michelangelo’s mother became ill and died, he was sent to live with a wet nurse in the nearby town of Settignano, where her family worked as stonecutters. Growing up in this environment, surrounded by marble and chisels, likely planted the earliest seeds of his sculptural genius. As a child, Michelangelo was sensitive, intelligent, and deeply drawn to art, often preferring sketching and observing nature over traditional studies. He was known to be somewhat aloof and introspective, with a fierce independence and strong will that sometimes clashed with his family’s expectations. Even at a young age, he displayed remarkable artistic talent, and by the time he was a teenager, his skills in drawing and sculpture were apparent.

During the early 1480s, Michelangelo attended the Latin school of Francesco da Urbino, though he showed little interest in traditional education. Instead, he spent much time copying drawings and visiting churches to study frescoes. In 1487, at just twelve years old, he was apprenticed to the painter Domenico Ghirlandaio, marking the official beginning of his artistic training in one of Florence’s leading workshops.

After a brief apprenticeship with Ghirlandaio, Michelangelo was recommended to the Medici family and, by 1490, was studying at the Medici-sponsored sculpture garden under the guidance of Bertoldo di Giovanni. There, he gained exposure to classical antiquities and mingled with Florence’s intellectual elite, including Lorenzo de’ Medici, who became his patron. During this time, Michelangelo sculpted some of his early masterpieces, such as the Battle of the Centaurs. However, after Lorenzo died in 1492 and rising political unrest in Florence, Michelangelo left the Medici court. By 1494, with tensions escalating under Savonarola’s influence, he departed Florence for Bologna, seeking refuge and continuing his artistic development.

In 1496, at just 21 years old, Michelangelo sculpted a marble Cupid and, at the suggestion of a dealer, artificially aged it to appear ancient. The sculpture was sold to Cardinal Riario of San Giorgio in Rome, who later discovered the deception. Rather than being outraged, the Cardinal was so impressed by Michelangelo’s skill that he invited the young artist to Rome — an invitation that launched his rise to fame.

Michelangelo traveled to Rome, where he created the Bacchus, a sensuous marble statue that impressed Roman patrons. His breakthrough came in 1498 when he was commissioned to sculpt the Pietà for St. Peter’s Basilica — an extraordinary work that blended delicate emotion with technical brilliance. In 1501, Michelangelo returned to Florence and received the commission for what would become one of his most iconic masterpieces: the colossal marble statue of David, which was completed in 1504 and instantly hailed as a symbol of civic pride and artistic genius.

Michelangelo then began work on the Battle of Cascina fresco, though it remained unfinished. In 1505, Pope Julius II summoned him to Rome to design a grandiose tomb, a project plagued by delays and complications. Tensions with the Pope led Michelangelo to briefly flee Rome, but in 1508 he was called back — this time to begin one of the most ambitious artistic feats in history: painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, the large papal chapel built within the Vatican between 1477 and 1480.

Michelangelo became immersed in the monumental task of painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling, a commission that would define his legacy. Working largely alone under grueling conditions, he completed the frescoes in 1512, unveiling a breathtaking vision of biblical scenes — from the Creation of Adam to the prophets and sibyls — that stunned the world and redefined Renaissance art. Following this triumph, he returned briefly to work on Pope Julius II’s tomb and created the powerful Moses statue.

In 1513, after Julius’s death, Pope Leo X, a member of the powerful Medici family, known for their wealth and patronage of the arts, came to power, and Michelangelo shifted focus to new architectural and sculptural projects. Under the patronage of the new pope, Michelangelo was tasked with designing the façade of the Church of San Lorenzo, but despite years of planning and sourcing marble from the quarries at Carrara, the project was ultimately abandoned due to funding and political complications. During this time, he also began work on the Medici Chapel, intended as a grand mausoleum for his patrons. Though progress was slow and frequently interrupted, this period marked a deepening of his architectural vision and further solidified his role as both a sculptor and architect of major importance.

Michelangelo worked intensively on the Medici Chapel in Florence, crafting striking tomb sculptures like Night and Day and Dawn and Dusk, which blended spiritual symbolism with anatomical mastery. In 1527, political upheaval shook Florence when the Medici were temporarily overthrown and the city became a republic. Michelangelo, a supporter of the republic, was appointed chief of fortifications and oversaw the city’s defenses against the impending siege by Medici and imperial forces. This marked a rare period where the artist became directly involved in military engineering, blending creativity with civic duty during a time of political crisis.

After the fall of the Florentine Republic in 1530 and the return of Medici rule, Michelangelo was briefly out of favor and feared retribution for his role in defending the republic. However, thanks to powerful allies and his immense reputation, he was pardoned and allowed to continue his work. He resumed and advanced the Medici Chapel and also began work on the Laurentian Library, designing its striking staircase and innovative architectural features. During this period, Michelangelo’s artistic focus began shifting increasingly toward architecture, and his work grew more spiritually introspective and monumental in tone.

Michelangelo held a deeply personal and evolving spiritual perspective, rooted in his Catholic faith yet infused with a profound sense of inner struggle and longing for divine truth. He believed that art was a path to God, a sacred act of revealing the divine through the beauty of the human form. In his later years, his work and poetry became increasingly contemplative, expressing remorse, humility, and a yearning for spiritual salvation. For Michelangelo, the creative act was both a gift from God and a form of worship— a means of sculpting the soul toward grace.

Michelangelo deepened his work in both sculpture and architecture while continuing to navigate shifting political and religious tides. He remained in Florence for part of this time, refining the Medici Chapel and Laurentian Library, though progress was slow due to interruptions and conflicts. In 1534, following the death of his beloved friend and muse Vittoria Colonna and amid growing tensions in Florence, Michelangelo left the city for good and settled permanently in Rome. There, Pope Paul III commissioned him to paint The Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel — a vast and emotionally charged fresco that he began in 1536 and completed in 1541, unveiling a work of awe, fear, and divine reckoning that stunned the world and cemented his spiritual and artistic legacy.

During the late 1540s, Michelangelo’s focus shifted increasingly toward architecture and religious devotion. He continued working under Pope Paul III and was appointed chief architect of St. Peter’s Basilica in 1546, a role he accepted reluctantly but would hold for the rest of his life. Michelangelo reimagined the basilica’s design with bold, unified forms, laying the groundwork for its majestic dome. During this time, he also worked on the Capitoline Hill redesign and created deeply personal sculptures like the Florentine Pietà, reflecting his preoccupation with mortality and faith in his later years.

During the 1550s, Michelangelo remained in Rome, dedicating himself almost entirely to architecture and religious art in his final decades. He continued refining the design and construction of St. Peter’s Basilica, focusing on the great dome and simplifying the plans to emphasize harmony and grandeur. He also worked on the Porta Pia and the Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri, transforming ancient Roman ruins into a Christian church. Despite his age, he remained fiercely productive, driven by spiritual conviction, and developed increasingly abstract and emotionally intense sculptural works, many of which he never completed. These years reflect a period of profound introspection and enduring creative power.

During the early 1560s, Michelangelo, now in his 80s, continued to work with remarkable dedication, primarily overseeing the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. He devoted himself to perfecting the design of its massive dome, which would become one of the most iconic architectural achievements in history. During these years, his art grew increasingly introspective and spiritual, as seen in his unfinished sculptures like the Rondanini Pietà, a raw and poignant reflection on suffering and mortality. Though he rarely left his home, Michelangelo remained an influential cultural figure, corresponding with artists and thinkers, and in 1563, he was named honorary president of the newly founded Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence, recognizing his unparalleled contributions to art and architecture.

In the final year of his life, Michelangelo remained mentally sharp and spiritually reflective. He continued to advise on the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica until just days before his death, and worked intermittently on the Rondanini Pietà. Michelangelo died in 1564, at the age of 88, in Rome. Honoring his wishes, his body was secretly transported to Florence, where he was buried with great ceremony at the Basilica of Santa Croce. Revered as a divine genius even in his lifetime, Michelangelo’s death marked the end of an era, but his legacy would shape Western art for centuries to come.

Michelangelo’s legacy is that of a visionary who redefined the boundaries of art, architecture, and human creativity. His masterpieces — such as David, the Pietà, the Sistine Chapel ceiling, and the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica— remain among the most celebrated works in Western history, exemplifying both technical brilliance and profound emotional depth. As a sculptor, painter, architect, and poet, he embodied the Renaissance ideal of the universal genius, and his influence echoes through centuries of artists who followed. Michelangelo’s work continues to inspire awe, not only for its beauty and skill, but for its spiritual intensity and enduring quest to capture the divine within the human form.

Some of the quotes that Michelangelo is known for include:

If people knew how hard I had to work to gain my mastery, it would not seem so wonderful at all.

The greatest danger for most of us is not that our aim is too high and we miss it, but that it is too low and we reach it.

If you knew how much work went into it, you wouldn’t call it genius.

Genius is eternal patience.

I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.

The sculpture is already complete within the marble block, before I start my work. It is already there, I just have to chisel away the superfluous material.

Lord, grant that I may always desire more than I accomplish.

Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.

The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of Danish physicist and philosopher Niels Bohr, who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922. He was also one of the first to consider and explore “quantum metaphysics,” the notion that matter is derived from consciousness.

Niels Henrik David Bohr was born in Copenhagen, Denmark in 1885. He was the second of three children. His father was a professor of physiology, and his mother came from a wealthy Jewish banking family.

When he was seven, Bohr started his education at Gammelholm Latin School. In 1903, he enrolled at Copenhagen University, where he studied physics, astronomy, mathematics, and philosophy. In 1905, Bohr won a gold medal competition for a physics contest measuring the surface tension of liquids, that he had to make his specialized glassware for. He later submitted an improved version of this paper, which was published by the Royal Society of London.

In 1909, Bohr received his master’s degree in mathematics, and in 1911 he received his doctorate in physics from Copenhagen University for his research into the magnetic properties of metals. During this time Bohr also met and married Margrethe Norlund, a Danish woman who collaborated with him on his research and helped to edit and transcribe his work.

In 1911, Bohr traveled to England, where most of the theoretical work on the structure of atoms and molecules was being done. He studied electromagnetism and researched cathode rays. In 1912, he began teaching physics to medical students at the University of Copenhagen, and in 1913 he did revolutionary work on creating a new model of the atom that became known as the “Bohr model” of the atom, which is the most basic particle of the chemical elements. This model of the atom consists of a small, dense nucleus surrounded by orbiting subatomic particles called “electrons,” in a way that is analogous to the structure of the solar system.

Bohr advanced atomic theory by proposing that electrons travel in orbits around the nucleus, or center of the atom, in “stationary states” that stabilize the atom. Bohr also introduced the idea that an electron could drop from a higher-energy orbit to a lower one, and in this process emit a “quantum” of discrete energy.

A quantum is the minimum amount of energy in any physical interaction between the fundamental forces of nature. Bohr’s theory became a basis for what is now known as the “old quantum theory”—which predates modern quantum mechanics. This was considered a breakthrough by many physicists of his day, including Albert Einstein.

In 1916, Bohr was appointed as the Chair of Theoretical Physics at the University of Copenhagen, a position that was created especially for him. In 1918, he established an Institute of Theoretical Physics at the university, where he became the director, and this institute is today known as the Niels Bohr Institute. Bohr was extremely dedicated to this work, and he and his family moved into an apartment on the first floor. Bohr’s institute served as a focal point for researchers into quantum mechanics during the 1920s and 1930s, when most of the world’s best-known theoretical physicists spent time there.

In 1919, Bohr revised his model of the atom, and its relationship with electrons, and in 1921, he published a paper that showed that the chemical properties of each element were largely determined by the number of electrons in the outer orbits of its atoms. In 1922, Bohr was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics “for his services in the investigation of the structure of atoms and the radiation emanating from them.”

In 1924, physicist Werner Heisenberg — who developed the mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics, and a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics known as the “uncertainty principle”— came to the University of Copenhagen, where he worked as an assistant to Bohr from 1926 to 1927, and they had an important influence on one another. Around this time, Bohr became convinced that light behaved like both waves and particles, and he conceived the philosophical principle of “complementarity,” which proposed that physical structures could have, what appear to be, mutually exclusive properties — such as being a wave or a stream of particles, depending on the experimental framework, or one’s perspective.

Heisenberg said that Bohr was “primarily a philosopher, not a physicist.” Bohr was influenced by Soren Kierkegaard’s philosophy, and he had an interest in metaphysics and psychic phenomena. In 1932, Bohr met with psychiatrist Carl Jung at a conference on intellectual cooperation, and they discussed the concept of synchronicity— the simultaneous occurrence of events that appear significantly related but have no discernible causal connection. Bohr was also interested in the concept of psychokinesis — the influencing of matter by thought — and he believed that parapsychology was worthy of study. Bohr was also one of the first to consider and explore the concept of “quantum metaphysics,” the notion that matter is derived from consciousness.

In 1940, early in the Second World War, Nazi Germany invaded and occupied Denmark. In 1943, word reached Bohr that the Nazis considered him to be Jewish since his mother was Jewish and that he was therefore in danger of being arrested. The Danish resistance helped Bohr and his wife escape to Sweden.

In 1943, Bohr arrived in Washington, D.C., where he met with the director of the Manhattan Project, the research program that led to the development of the atomic bomb. Bohr visited Einstein at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, and went to Los Alamos in New Mexico, where the atomic bomb was being designed.

Bohr did not remain at Los Alamos, but he paid a series of extended visits there over the next two years. Physicist Robert Oppenheimer credited Bohr with acting “as a scientific father figure to the younger men” that were there, and Oppenheimer gave Bohr credit for an important contribution to the work on an essential part of the project called “modulated neutron initiators.” “This device remained a stubborn puzzle,” Oppenheimer said, “but in early February 1945 Niels Bohr clarified what had to be done.”

Following the end of the war in 1945, Bohr returned to Copenhagen, where he was elected as president of the Royal Danish Academy of Science. In 1947, the king of Denmark, Frederik IX, awarded Bohr with membership in the Order of the Elephant — a Danish order of chivalry and is Denmark’s highest-ranked honor — which was normally only awarded to royalty and heads of state. Bohr designed his coat of arms, which included a Chinese yin-yang symbol in its center, signifying that “opposites are complementary.” Bohr also received numerous other awards and honors, such as the Matteucci Medal, the Copley Medal, and the Atoms for Peace Award.

In 1962, Bohr died of heart failure at his home in Carlsberg, Denmark.

In 1963, the Bohr model’s semi-centennial was commemorated in Denmark with a postage stamp depicting Bohr, the hydrogen atom, and the formula for the difference in hydrogen energy levels. Several other countries have also issued postage stamps depicting Bohr. In 1997, the Danish National Bank began circulating the 500-krone banknote with a portrait of Bohr smoking a pipe. Additionally, an asteroid, 3948 Bohr, was named after him, as was the Bohr Lunar Crater, and Bohrium, the chemical element with atomic number 107.

Some of the quotes that Niels Bohr is known for include:

Everything we call real is made of things that cannot be regarded as real. If quantum mechanics hasn’t profoundly shocked you, you haven’t understood it yet.

An expert is a person who has made all the mistakes that can be made in a very narrow field.

The opposite of a correct statement is a false statement. But the opposite of a profound truth may well be another profound truth.

No, no, you’re not thinking; you’re just being logical.

There are some things so serious that you have to laugh at them.

A physicist is just an atom’s way of looking at itself.

The meaning of life consists in the fact that it makes no sense to say that life has no meaning.

We must be clear that when it comes to atoms, language can be used only as in poetry. The poet, too, is not nearly so concerned with describing facts as with creating images and establishing mental connections.

Every sentence I utter must be understood not as an affirmation, but as a question.

Your theory is crazy, but it’s not crazy enough to be true.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, whose painting The Scream has become one of Western art’s most iconic images. Munch is also known for his “soul paintings,” and he was knighted by Norwegian royalty.

Edvard Munch was born in Adalsbruk, Norway in 1863. His father was a doctor and medical officer, who Munch described as “obsessively religious.” His mother was artistically talented, and she encouraged her son to express himself creatively. Munch had an older sister and three younger siblings.

In 1864, Munch’s family moved to Oslo. In 1868, his mother, as well as his older sister, died of tuberculosis, which had a profound impact on him. After his mother’s death, his aunt helped to raise the family. Munch was often ill as a child and kept out of school. During this time, he would often spend his time drawing and painting in watercolors. Munch was tutored in history and literature by his father, who often entertained the family with stories by the American writer Edgar Allan Poe.

The combination of an oppressive religious environment, his poor health, and vivid mystery stories by Poe, worked together to instill nightmares and macabre visions in young Munch’s mind. One of his younger sisters was diagnosed with mental illness at an early age and committed to a mental asylum. There was so much darkness in Munch’s early life that he often expressed the fear that he was going insane.

Munch’s earliest drawings and watercolors depicted the interior of his home and medicine bottles, but he soon began painting some landscapes. By the time Munch was a teenager, art became his primary interest. In 1876, Munch had his first exposure to other artists at the Norwegian Landscape School, where he began to paint in oils and tried to copy the paintings that he was exposed to.

In 1879, Munch enrolled in a technical college, where he studied engineering and excelled in physics, chemistry, and mathematics. He also learned scaled and perspective drawing techniques. Although he did well in college, he left school after just a year, with the determination to become a painter. Munch’s father was disappointed in his son’s decision, as he viewed art as an “unholy trade.” However, Munch saw his art as his salvation, and wrote the following in his diary around this time: “In my art, I attempt to explain life and its meaning to myself.”

In 1881, Munch enrolled at the Royal School of Art and Design in Oslo, which was founded by a distant relative. In 1883, Munch took part in his first public exhibition, and he became friendly with other art students. Munch was inspired by the art movement of Impressionism, which is characterized by small but visible brushstrokes that emphasize the depiction of light in its changing qualities. He was also influenced by Naturalism, which, in contrast, attempts to represent subject matter realistically, and he later became associated with the Symbolist Movement, which sought to depict ideas and emotions hidden behind physical reality.

Munch’s early work consisted largely of self-portraits and nudes. Sadly, all but one of his nude paintings from this period survive, as the others were destroyed by his father, who then refused to give his son any further money for art supplies. In 1886, Munch concluded that Impressionism was too superficial, and he broke off into new experimentation with what he called “soul painting.” This approach to his art served as a means of exploring and expressing the innermost feelings, thoughts, and experiences of the human psyche.

Munch believed that art should transcend the visual representation of the external world and delve into the subjective experience of the individual. “Soul painting” was not just a technique but a philosophy for Munch. It was about revealing the internal struggles and deeper realities of human existence, “making visible what was invisible to the eye.” Through “soul painting,” Munch aimed to capture the anguish, loneliness, love, and despair that he felt and perceived in others. His “soul paintings” were characterized by their evocative use of color, dramatic compositions, and often unsettling subjects that reflect complex emotional states.

His first painting of this type was The Sick Child, which was based on his sister’s death. This painting evolved into six paintings with that title, which record the moment before the passing of his older sister. These six paintings were created over more than forty years, between 1885 through 1926. They all depict variant images of the same scene; his sister lying ill in bed with his aunt kneeling beside her.

In 1889, Munch moved to Paris, and one of his paintings was shown at the Paris Exposition that year. He spent his time at exhibitions, galleries, and museums. Later that year his father died, and Munch returned to Oslo. While he was there, he arranged for a large loan from a wealthy Norwegian art collector and assumed financial responsibility for his family from then on. Munch’s paintings during this time were largely of tavern scenes and bright cityscapes, and he experimented with different painting styles. Around this time, his work was shown at exhibitions in Oslo and also in Berlin. In 1892, he moved to Berlin, where he became involved with an international circle of writers and artists, and he stayed there for four years.

In 1893, Munch created the first version of his most well-known painting The Scream. This is Munch’s most famous work and one of the most recognizable paintings in all art history. It has been widely interpreted as representing the universal anxiety of modern man. Painted with broad bands of garish color and simplified forms, it reduces the agonized figure to a garbed skull in the throes of an emotional crisis.

There are several versions of this famous painting: two pastels, two oil paintings, and a lithograph. Pastel versions and the lithograph version were created in 1895. The second oil painting was completed in 1910. The original inspiration for this painting occurred while Munch had been out for a walk at sunset when suddenly the setting sun’s light turned the clouds “a blood red,” and he sensed an “infinite scream passing through nature.”

In 1908, Munch’s anxiety, which was compounded by excessive drinking, became more acute, and he began to suffer from hallucinations and feelings of persecution. This led to an eight-month hospital stay, where he underwent psychotherapy that stabilized his mind, and when he returned home his artwork was transformed. It became more colorful and less pessimistic. There was also more interest in his work after this dark night of the soul, and museums began to purchase his paintings. He was made a Knight of the Royal St. Olav — a Norwegian Order of Chivalry— “for services in art.” In 1912, he had his first American exhibit in New York.

Munch stopped drinking, and he produced portraits of friends and patrons. He also created landscapes and scenes of people at work and play, using a new optimistic style— broad, loose brushstrokes of vibrant color with frequent use of white space. With more income Munch was able to purchase several properties, giving him new vistas for his art, and he was finally able to provide for his family.

Munch spent the last two decades of his life largely in solitude at his estate in Oslo. Many of his late paintings celebrate farm life, including several in which his horse served as a model. Munch died in 1944, at the age of 80. After Munch died, many of his works were bequeathed to the city of Oslo, which built the Munch Museum. The museum houses the largest collection of his work in the world and holds around 1,100 paintings, 4,500 drawings, and 18,000 prints.

In 1974, a biographical film was made about Munch’s life called Edvard Munch. In 1994, the 1893 version of The Scream was stolen from the National Gallery in Oslo but was later recovered. Then in 2004, the 1910 version of the painting was stolen from the Munch Museum in Oslo, and it was recovered in 2006 with some damage. In 2012, the 1895 pastel version of The Scream sold for $119,922,500, and that is the only version of the painting not held by a Norwegian museum.

Some of the quotes that Edvard Munch is known for include:

From my rotting body, flowers shall grow, and I am in them, and that is eternity.

Nature is not only all that is visible to the eye… it also includes the inner pictures of the soul.

I was walking along a path with two friends – the sun was setting – suddenly the sky turned blood red – I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence – there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city – my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.

The camera will never compete with the brush and palette until such time as photography can be taken to Heaven or Hell.

My fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness. Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder. My art is grounded in reflections over being different from others. My sufferings are part of myself and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art. I want to keep those sufferings.

I felt as if there were invisible threads connecting us— I felt the invisible strands of her hair still winding around me— and thus as she disappeared completely beyond the sea— I still felt it, felt the pain where my heart was bleeding— because the threads could not be severed.

Your face encompasses the beauty of the whole earth. Your lips, as red as ripening fruit, gently part as if in pain. It is the smile of a corpse. Now the hand of death touches life. The chain is forged that links the thousand families that are dead to the thousand generations to come.

Carolyn and I have admired the work of American painter Jackson Pollock, who was a leading figure in the abstract expressionism art movement, which was characterized by freely associative painting styles that helped the art world to redefine what a painting could be. Pollock is most well-known for developing the “drip technique,” a painting method that involves dripping, pouring, or splashing paint onto a horizontal surface, enabling the artist to paint his or her canvas from multiple angles. Pollock’s revolutionary work influenced many subsequent art movements that followed abstract expressionism.

Paul Jackson Pollock was born in Cody, Wyoming in 1912. His father, who was of Scottish-Irish descent, was a farmer and land surveyor for the government. Pollock’s mother came from an Irish family with a heritage of weavers, and she made and sold dresses. Pollock’s family left Wyoming when he was 11 months old, and he grew up in Arizona and California. Pollock’s childhood wasn’t very stable; his family moved nine times in the next 16 years, and in 1928 Pollock was expelled from two high schools for being a “troublemaker.”

In 1928, Pollock enrolled at the Manuel Arts School in Los Angeles, where he met painter and illustrator Frederick Schwankovsky, who gave him some training in drawing and painting and encouraged his interest in metaphysical and spiritual literature. Schwankovsky was a member of the Theosophical Society and was friends with Jiddu Krishnamurti. These early spiritual explorations may have influenced Pollock, as in subsequent years he embraced the theories of Swiss psychologist Carl Jung and the notion of unconscious imagery being expressed in his painting.

In 1930, Pollock moved to New York City, where his older brother was living, and he studied drawing, painting, and composition at the Art Students League. In 1936, Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros introduced Pollock to the use of liquid paint at an experimental workshop, and he later used paint pouring as one of his painting techniques. During this time Pollock’s painting style was part of the regionalism movement that depicted realistic scenes, and his style slowly began to become more abstract.

Around this time, Pollock began drinking too much. In 1937, he began treatment for a problem with alcoholism by undergoing Jungian psychotherapy. In 1938, he suffered a nervous breakdown, which caused him to be institutionalized for about four months, and his treatment involved being engaged with his art. Pollock was encouraged to make drawings and to see Jungian concepts and archetypes expressed in his paintings, as a way of exploring his unconscious mind.

From 1938 to 1942, Pollock found work as an easel painter with the Federal Arts Project, a federal program that helped struggling artists find employment during the Great Depression. In the early 1940s, Pollock moved to Springs, New York, and began developing his “drip” technique, with his canvases laid out on the studio floor. Pollock’s technique typically involved pouring paint straight from a can or along a stick onto a canvas lying horizontally on the floor.

In 1942, Pollock met the artist Lee Krasner at a gallery exhibition. They became romantically involved, influenced one another’s art, and in 1945 the couple was married. Krasner had extensive knowledge and training in modern art, and she introduced Pollock to many collectors, critics, and other artists who would further his career.

In 1943, Pollock signed a gallery contract with Peggy Guggenheim, and he did his first wall-sized work, a huge 8-by-20-foot abstract oil painting titled Mural. The painting was commissioned for the entrance hall of Guggenheim’s townhouse in NYC. In the foreword to the exhibition catalog, a New York Times reviewer described Pollock’s creativity as “…volcanic. It has fire. It is unpredictable. It is undisciplined. It spills out of itself in a mineral prodigality, not yet crystallized.” Mural represents Pollock’s “breakthrough into a totally personal style in which compositional methods, and energetic linear invention, are fused with the Surrealist free association of motifs and unconscious imagery.”

Between 1947 and 1950 was Pollock’s “drip period,” when he produced some of his most famous abstract paintings. The process involved pouring or dripping paint onto a flat canvas in stages, often alternating weeks of painting with weeks of contemplating, before he finished a canvas. A whole series of famous paintings were created during this period, such as Full Fathom Five, Lucifer, and Summertime. Pollock also created more mural-sized canvases, such as One, Autumn Rhythm, and Lavender Mist.

In 1949, Life magazine did a four-page spread of Pollock’s work, and the accompanying article suggested that he might be the “greatest living painter” in the United States. Then, at the peak of his fame, Pollock abruptly abandoned the drip style of painting. He began attempting to balance abstraction with depictions of figures in his paintings and used darker colors.

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Pollock had one-man shows of new paintings nearly every year in New York. His work was handled by Peggy Guggenheim through 1947, then by the Betty Parsons Gallery from 1947 to 1952, and then by the Sidney Janis Gallery from 1952 onward.

After 1953, Pollock’s health began to deteriorate, and his production began to wane, but he still produced a number of important paintings in his final years, such as White Light and Scent. In 1956, Pollock died in a single-car crash while under the influence of alcohol.

Four months after his death, Pollock was given a memorial retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Pollock did not profit financially from his fame. During his lifetime, Pollock never sold a painting for more than $10,000 and was often hard-pressed for cash, but in 2016, his painting “umber 17A sold for $200 million. Now considered an “iconic” master of mid-century Modernism, his work influenced the American art movements that immediately followed Abstract Expressionism — such as Happenings, Pop Art, Op Art, and Color Field painting.

One of the things that I’ve found most intriguing about Pollock’s art is how it continues to be controversial, almost seven decades after his death. It’s not uncommon to hear people say“It’s just the flinging of paint!” This leads me to believe that Pollock’s critics, be they of his time or ours, are largely wrong — for it’s hard for me to understand why people would get so worked up over an artist, almost 70 years after his death unless there’s something in his work that truly matters.

Some of the quotes that Jackson Pollock is known for include:

Painting is self-discovery. Every good artist paints what he is.

New needs need new techniques. And the modern artists have found new ways and new means of making their statements… the modern painter cannot express this age, the airplane, the atom bomb, the radio, in the old forms of the Renaissance or of any other past culture.

On the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting.

The secret of success is… to be fully awake to everything about you.

There is no accident, just as there is no beginning and no end.

The painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through.

When I’m painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing. It’s only after a get acquainted period that I see what I’ve been about. I’ve no fears about making changes for the painting has a life of its own.

Modern artists unravel inner universes, expressing energy, motion, and latent forces.

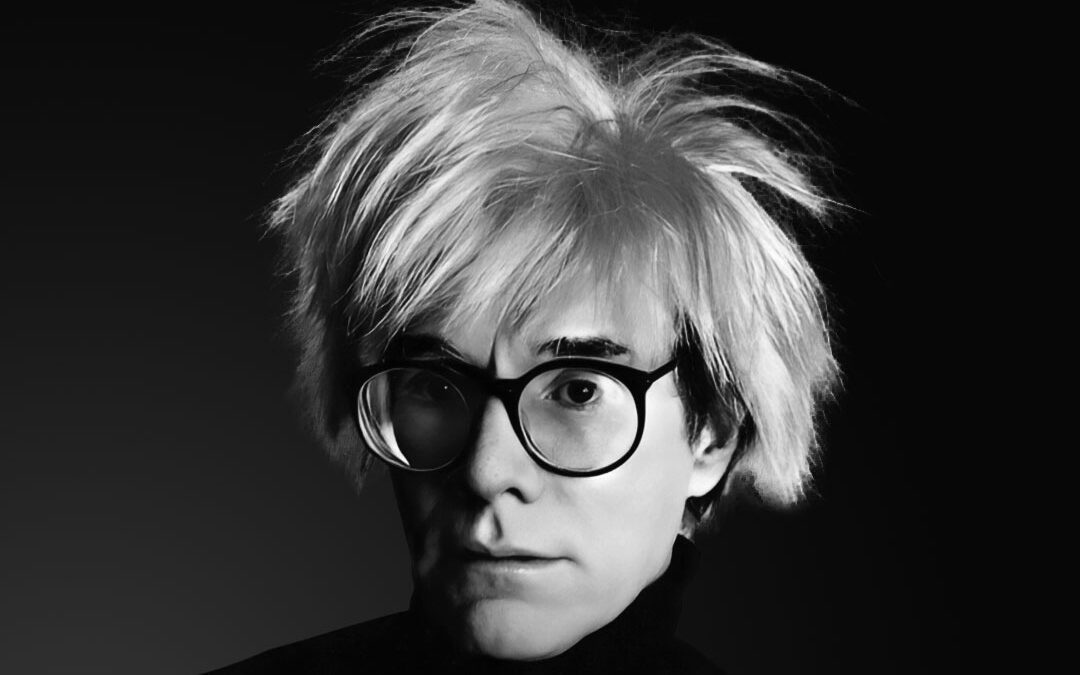

Carolyn and I have admired the work of visual artists, film directors, and leading figures in the Pop Art movement Andy Warhol. His work explores the relationship between artistic expression, advertising, and celebrity culture, in a variety of media, including painting, silk-screening, photography, film, and sculpture. Warhol’s work embraces and celebrates the banality of American culture, and he is well known for his witty and insightful quotes.

Andrew (Andy) Warhola Jr. was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1928. He was the fourth child in a working-class family, whose parents were emigrants from a geographical region that is now located in Slovakia. Warhol’s father worked in a coal mine and died in a car accident when Andy was thirteen.

In 1936, when Warhol was eight years old, he became infected with a nervous system affliction that caused involuntary movements in his extremities, and he was confined to bed for over two months. Warhol described this period as being an important developmental stage in his life, which was largely spent listening to the radio and collecting pictures of movie stars around his bed.

In 1945, Warhol graduated from Schenley High School in Pittsburgh, and he won a Scholastic Art and Writing Award. Warhol enrolled at Carnegie Mellon University, where he studied commercial art. In 1947 and 1948 Warhol’s illustrations appeared on the cover and interior of his student magazine. In 1949, Warhol earned his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in pictorial design, and his first commissions were to draw shoes for Glamour magazine.

In 1950, Warhol moved to New York City, where he began a career in magazine illustration and advertising, and his first job in the city was designing shoes for a shoe manufacturer. While working in the shoe industry, Warhol developed a “blotted line” printing technique, which involved applying ink to paper and then blotting the ink while still wet. His use of tracing paper and ink allowed him to repeat— and to create endless variations— of a basic image; a process that became important in his later work.

In 1952, Warhol had his first solo show, of his whimsical ink drawings of shoe advertisements, at the Hugo Gallery in New York (although that show was not very well received). In 1956, some of his work was included in a group exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in NYC. Warhol began creating art by tracing projected photographs, subtly alerting the image, such as his 1956 image of a Young Man Smoking a Cigarette.

It was around this time, in the late 1950s, that Warhol was hired by RCA Records to design record album covers and promotional materials. In 1962, Warhol learned silk screen printmaking techniques, and he began to participate in the Pop Art movement. Pop Art was a British and American art movement that emerged in the mid to late 1950s, and is based on imagery from modern popular culture and the mass media. Pop Art was largely viewed as a critical or ironic comment on traditional fine art values, and often used imagery that had been commonly used in advertising or comic books.

In 1962, Warhol was featured in an article in Time magazine with his painting Big Campbell’s Soup Can with Can Opener (Vegetable), which became his most sustained motif— the Campbell’s soup can. The painting was exhibited at the Wadsworth Museum in Connecticut that year, and a year later Warhol made his West Coast debut with his Campbell’s Soup Cans exhibition at Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. That same year, Warhol also had exhibits at the Stable Gallery and the Museum of Modern Art in NYC, including a silkscreened painting series of iconic American images and objects, such as Marilyn Monroe portraits, Coca Cola bottles, and $100 bills.

In 1963, Warhol rented an old firehouse on East 47th Street in NYC that became his art studio and would turn into a legendary location called The Factory, where Warhol’s workers made silkscreens and lithographs under his direction. The Factory became famous for its exclusive parties in the 1960s, and was a hip hangout for artists, musicians, and celebrities, such as Allen Ginsberg, Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, and the Velvet Underground. Warhol created a Pop Art empire, and at exhibits he sold autographed soup cans and “sculptures” of boxes with commercial logos on them.

In 1968, there was an assassination attempt on Warhol by a radical feminist writer named Valerie Solanas, who shot Warhol at The Factory, but only minor injuries were sustained. Solanas was subsequently arrested and diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia.

In 1969, Warhol co-founded Interview magazine with a British journalist. The magazine features in-depth, usually unedited interviews with celebrities, artists, musicians, and creative thinkers. It is still in print today.

In 1971, Warhol had a retrospective exhibition of his work at the Whitney Museum of American Art in NYC. In 1975, he published his book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, which is a loosely formed autobiography. Although criticized as being merely a “business artist,” some critics have come to view Warhol’s superficiality and commerciality as “the most brilliant mirror of our times,” contending that “Warhol had captured something irresistible about the zeitgeist of American culture.”

Warhol also directed or produced hundreds of experimental films, and dozens of full-length movies—silent and sound, short and long, scripted and improvised— fifty of which have been preserved by the Museum of Modern Art. The styles range from minimalist avant-garde to more commercial productions. The Andy Warhol Film Project seeks to preserve Warhol’s nearly 650 films.

Warhol once said, “I’d like to be a machine, wouldn’t you?” In 1981, he got his wish when he worked on a project that was to create a traveling stage show— called A No Man Show— with a life-sized animatronic robot in the image of Warhol. The Andy Warhol Robot would then be able to read Warhol’s diaries as a theatrical production. This project was left unfinished when Warhol died, and over $400,000 was spent to create a Warhol robot, which is now in the hands of a private collector.

Warhol died in 1987 in New York City. After he died, Warhol’s body was brought back to Pittsburgh, where an open-coffin wake was held. The solid bronze casket had gold-plated rails and white upholstery. Warhol was dressed in a black cashmere suit, a paisley tie, a platinum wig, and sunglasses. He was laid out holding a small prayer book and a red rose, and the coffin was covered with white roses and asparagus ferns.

Warhol is remembered as one of the founding fathers of the Pop Art movement, and for challenging the very definition of art. Warhol’s artistic risks, and his lifelong experimentation with different subjects and media, made him a pioneer in almost all forms of visual art.

Some of the quotes that Andy Warhol is known for include:

Don’t pay any attention to what they write about you. Just measure it in inches.

If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.

In the future, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes.

Art is already advertising. Mona Lisa could have been used to support a brand of chocolate, Coca-Cola, or anything else.

Being born is like being kidnapped. And then sold into slavery.

I am a deeply superficial person.

We seek to last more than we try to live.

When you work with people who misunderstand you, instead of getting transmissions, you get transmutations, and that’s much more interesting in the long run.

Carolyn and I have admired the work of French painter and sculptor Paul Gauguin, who was an influential post-Impressionist artist. Gauguin styled himself and his art as “savage, and he is particularly known for his experimental use of color, as well as for his paintings of the people and landscapes in Polynesia.

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin was born in Paris in 1848. His father was a journalist, and his mother was the daughter of a proto-socialist leader. Due to the political climate in France at the time, in 1850 Gauguin’s family sailed to Peru and his father died of a heart attack on the voyage. Gauguin lived in Lima for four years with his uncle, mother, and sister.

It was in Lima that Gauguin first encountered art, when his mother collected Pre-Columbian Inca pottery. In 1855, Gauguin and his family returned to France, where he lived with his grandfather in Orleans. Gauguin learned to speak French, although his first and preferred language remained Peruvian Spanish. Gauguin attended a Catholic boarding school, and although he did well in his studies, he disliked the school.

In 1865, Gauguin joined the merchant marines, and three years later he joined the French navy, where he served for two more years. In 1871, Gauguin returned to Paris where he worked as a stockbroker, and he became a successful businessman for eleven years. Gauguin came to art late in his life; he had no formal art training, and there is little in his early life that seems to predict his outstanding artistic career.

In 1873, Gauguin married a Danish woman, and over ten years they had five children. It was around this time that Gauguin began painting in his spare time. Gauguin also visited galleries and collected works by Impressionist artists. Gauguin formed a friendship with Camille Pissarro, and he visited him on Sundays to paint in his garden. Pissarro introduced Gauguin to a community of other artists, such as Paul Cézanne, who he also occasionally painted with. In 1881 and 1882, Gauguin showed paintings at Impressionist exhibitions in Paris, although he received dismissive reviews at the time.

In 1884, Gauguin moved his family to Copenhagen, Denmark, where he pursued a new career as a tarp salesman, which he wasn’t very successful at, perhaps because he couldn’t speak Danish, and there wasn’t much a market for French tarps in Denmark. However, Gauguin’s wife was able to support them by giving French lessons to diplomats.

It was during this time that Gauguin’s marriage began to fall apart, the stock market crashed, and he began painting full-time. In 1885, Gauguin returned to Paris, where he initially had difficulty re-entering the art world, lived in poverty, and was forced to take a series of menial jobs. However, Gauguin continued to paint, and in 1886 he exhibited 19 paintings at the last Impressionist exhibition, although many of these paintings were from very earlier periods in his life, such as from his time in Denmark.

In 1886, Gauguin spent time at an artist’s colony in Brittany, where he was popular with the young art students. In 1887, Gauguin sailed to a French Caribbean Island with painter Charles Laval, where he intended to “live like a savage.” Up until this point, Gauguin’s paintings were done in an Impressionist style, and this was where he changed his style. His paintings Tropical Vegetation and By the Sea were done in a new post-Impressionist style, where he began working with blocks of color in large, unmodulated planes.

Later that year Gauguin returned to France, where he adopted a new sense of identity— connected with his Peruvian ancestry, and incorporating “primitivism” into his artistic vision. Primitivism is a mode of aesthetic idealization that values that which is simple and unsophisticated, and seeks to express the experience of primitive times, places and people in art or literature, as well as in a philosophy of life.

In 1888, Gauguin began searching for what he called “a reasoned and frank return to… primitive art.” He began painting with broad planes of color, clear outlines, and more simplified forms. Gauguin coined the term “Synthetism” to describe his style during this period. This refers to the synthesis of his paintings’ formal elements with the ideas or emotions that they conveyed. Gauguin no longer used lines and color to replicate an actual scene, as he had as an Impressionist, but rather explored the capacity of those pictorial forms to induce a particular feeling in the viewer.

That same year Gauguin traveled to the south of France, where he went to stay with Vincent van Gogh in Arles. This was done partially as a favor to van Gogh’s brother, Theo, who was an art dealer that had agreed to represent Gauguin. However, as soon as Gauguin arrived in Arles, the two artists began engaging in heated exchanges about the purpose of art. Gauguin had initially planned to stay in Arles through the spring, but his relationship with van Gogh grew ever more tumultuous. During a particularly intense quarrel, Gauguin claimed that van Gogh attacked him with a razor, and van Gogh then reportedly mutilated his own left ear. This proved to be too much for Gauguin to handle, and so he left for Paris after staying only two months.

Gauguin eventually relocated to the remote village of Le Pouldu. There, he engaged in a heightened pursuit of “raw expression,” and he became interested in the ancient monuments of medieval religion, such as crosses and representations of Christ’s crucifixion. Gauguin began incorporating this imagery into his artwork, such as in his painting The Yellow Christ. Gauguin said that he identified with Jesus, because he felt lonely and misunderstood, and he compared his suffering and burden to that of Jesus. In his artworks, Gauguin painted Jesus with some of his own facial features.

In 1891, Gauguin moved to Tahiti, where he had a romantic image of an untouched paradise. However, when he arrived he was disappointed by the extent to which French colonization had actually corrupted the island. Nonetheless, Gauguin attempted to immerse himself in what he believed were the authentic aspects of the culture there, and he emulated Oceanic traditions in his artwork during this period.

In 1893, Gauguin returned to France, thinking that his new work would bring him the success that had thus far eluded him. In 1894, Gauguin created a book of his impressions of Tahiti from his journals, illustrated with his own artwork, titled Noa Noa. However, this project, and an exhibit at a gallery in Paris, met with little success. Gauguin self-published the text from his diary at the time, and it wasn’t published until a hundred years later with the woodblock illustrations, drawings, and sketches that he originally intended to accompany the text.

In 1895, Gauguin left for Tahiti again. However, he was increasingly “disgusted” with the rising Western influence in the French colony. In 1901, Gauguin moved to a more remote environment, on the French Polynesian island of Hiva Oa. He purchased land there, and with the help of his neighbors, he built a home that he called “the house of pleasure.”

In 1902, Gauguin began suffering from an advanced case of syphilis, which restricted his mobility, and he concentrated his remaining energy on drawing and writing. During this time Gauguin worked on his memoir, Before or After. Gauguin died in 1903, at the age of 54, and his memoir wasn’t published for another twenty years.

After his death, Gauguin’s influence grew substantially. A large part of his collection is now displayed in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow and the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. Gauguin’s paintings are rarely offered for sale, but when they have been sold their prices reached tens of millions of dollars. Gauguin’s 1892 painting When Will You Marry? became the world’s third-most expensive artwork when it was sold for $210 million in 2014.

Some of the quotes that Paul Gauguin is known for include:

Color! What a deep and mysterious language, the language of dreams.

I shut my eyes in order to see.

Do not copy nature. Art is an abstraction. Rather, bring your art forth by dreaming in front of her and think more of creation.

Stay firmly in your path and dare; be wild two hours a day!

Color which, like music, is a matter of vibrations, reaches what is most general and therefore most indefinable in nature: its inner power.

Life is merely a fraction of a second. An infinitely small amount of time to fulfill our desires, our dreams, our passions. Such a little time to prepare oneself for eternity!

It is better to paint from memory, for thus your work will be your own.

Art is either revolution or plagiarism.

In order to produce something new, you have to return to the original source, to the childhood of mankind.