Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of Austrian/Czech novelist and Bohemian writer Franz Kafka, who is best known for his surreal and existential fiction that explores themes of alienation, absurdity, and the nightmarish aspects of modern bureaucracy. His most famous works include The Metamorphosis, The Trial, and The Castle. Although Kafka published only a few pieces during his lifetime and requested that his unpublished work be destroyed, a friend ignored this wish and posthumously published many of Kafka’s manuscripts — ensuring his lasting literary legacy. Today, Kafka is considered one of the most influential writers of the 20th century.

Franz Kafka was born in 1883, in Prague, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, into a middle-class Jewish family. He was the eldest of six children. His father was a self-made businessman who rose from humble beginnings to run a successful wholesale shop selling fine goods, including haberdashery and accessories. He was known for his authoritarian personality and strong work ethic. Kafka’s mother came from a more cultured and well-educated background, helping to manage the family business while also raising their six children. Though she was intelligent and capable, her influence was often overshadowed by her husband’s dominant presence in the household.

In these early years, Kafka lived in a predominantly Czech-speaking city, but his family spoke German at home, placing him between two cultures. The deaths of his two younger brothers in infancy during this period left a lasting emotional imprint on him. These formative experiences — marked by cultural tension, early loss, and a complex relationship with his father— would shape the emotional landscape of Kafka’s later writings.

As a child, Kafka was sensitive, introspective, and intellectually curious. He was often anxious and shy, with a strong imagination and a deep inner life. He felt overshadowed by his authoritarian father, which contributed to a sense of insecurity and emotional distance within the family. Though he excelled academically and loved reading, he often struggled with feelings of inadequacy and isolation, traits that would echo throughout his later writings.

Kafka began attending elementary school in 1889, at the age of six, and he entered the Altstädter Deutsches Gymnasium, a rigorous German-language secondary school in Prague, in 1893, around the age of ten. During this time, he distinguished himself as a bright and diligent student, developing a strong foundation in classical education, including Latin and German literature. He also began to show early signs of his literary interests and growing inner tension, particularly related to his father’s dominance and the pressures of academic life. These years marked the beginning of Kafka’s lifelong struggle to balance societal expectations with his deepening inner world.

Kafka continued his studies at the Altstädter Deutsches Gymnasium, graduating with honors in 1901. During these years, he deepened his interest in literature and philosophy, read widely, and began writing privately. Later that year, he enrolled at the German University in Prague, initially studying chemistry but quickly switching to law — a more practical field that satisfied his father’s expectations. He also formed lifelong friendships during this period, including with writer Max Brod, who would later play a crucial role in preserving and publishing Kafka’s work after his death.

Kafka completed his law degree at the German University in Prague, earning a doctorate in 1906. After a mandatory year of unpaid legal practice, he began working at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute in 1908 — a job that offered financial stability but left him feeling stifled and drained. During this time, he began writing more seriously and publishing short prose pieces, including Meditation in 1908. He also maintained close friendships with writers like Brod, who encouraged his literary ambitions. These years marked the emergence of Kafka’s dual life: dutiful bureaucrat by day, existential writer by night.

During the early 1910s, Kafka became increasingly dedicated to his writing, keeping a detailed diary that offered deep insight into his inner world. He wrote many of his most iconic works during this period, including both The Metamorphosis and The Judgment, both of which reflect his complex relationship with his father and his feelings of alienation. In 1912, he also began a tumultuous romantic relationship with Felice Bauer, leading to two engagements and eventual separation. Despite his growing literary success, Kafka struggled with physical and emotional health issues, including the onset of tuberculosis in 1915. These years were a creative high point but also marked by personal turmoil and illness.

Kafka’s novel The Metamorphosis is about a traveling salesman named Gregor Samsa who wakes up one morning to find himself transformed into a giant insect, leading to his alienation from his family and society as he grapples with his new, dehumanized existence. Kafka’s work, especially The Metamorphosis, often reads like a lucid nightmare or dream, blending mundane details with bizarre, inexplicable events that defy logic, much like the altered perceptions found in dreams or psychedelic states. His stories frequently evoke a sense of disorientation, symbolic transformation, and existential unease, echoing the inner landscapes explored in visionary consciousness.

In works like The Trial and The Castle, Kafka creates labyrinthine, irrational worlds that mirror the paradoxes and emotional intensity of deep dream states or psychedelic journeys, where meaning is elusive, identity is fluid, and invisible forces seem to govern one’s fate. His writing taps into the archetypal and the unconscious, offering a haunting glimpse into the liminal space between reality and the surreal. These dreamlike narratives also hint at a deeper metaphysical struggle, reflecting Kafka’s inner search for meaning and the spiritual anxieties that permeated his life.

Kafka’s spiritual perspective was complex and often conflicted. Though he was born into a Jewish family and maintained an intellectual interest in Judaism, especially in mysticism and Hasidic tradition, he struggled with religious belief and felt estranged from organized religion. His writings reflect a deep yearning for meaning, transcendence, and redemption, often portraying an elusive higher power or unreachable truth. Kafka’s spiritual outlook was marked by existential anxiety, guilt, and a sense of humanity’s alienation from the divine, yet also by a persistent, almost mystical hope for grace or understanding beyond the visible world.

After Kafka was diagnosed with tuberculosis, his health steadily declined, forcing him to take frequent leaves from work and he eventually retired in 1922. Despite his illness, he continued to write, producing some of his most powerful late works, including A Hunger Artist and The Burrow. Kafka also had significant relationships during this time, including Milena Jesenská, a Czech journalist and translator, and later with Dora Diamant, who was with him during his final days. Kafka spent much of this period in sanatoriums and rural retreats, seeking relief from his condition while continuing to reflect deeply on themes of suffering, isolation, and the absurd.

One of the most touching anecdotes from Kafka’s life occurred in 1923 when he encountered a little girl crying in a Berlin park because she had lost her doll. Kafka gently comforted her by inventing a story: the doll hadn’t disappeared, he said — it had gone on a journey. Over the following days, he returned to the park and read the girl the letters that he had written from the doll’s point of view, describing its adventures. This continued for weeks until Kafka had the doll “write” a final farewell, explaining it had settled down and was happy. The story reflects Kafka’s compassion and imaginative brilliance.

In the final year of his life, Kafka was gravely ill with advanced tuberculosis, which had spread to his throat and made it increasingly difficult for him to eat or speak. He spent his last months in a sanatorium in Kierling, near Vienna, cared for by his companion Dora Diamant. During this time, he continued to write when possible and edited his final collection, A Hunger Artist. Kafka died in 1924, at the age of 40, leaving behind a body of work that would profoundly influence modern literature after his death.

Kafka’s legacy lies in his profound influence on modern literature, particularly through his exploration of alienation, absurdity, and the oppressive nature of bureaucracy. Though little known during his lifetime, his posthumously published works, thanks to his friend Max Brod, became foundational to existential and modernist writing. The term “Kafkaesque” has entered the cultural lexicon to describe nightmarishly complex and illogical situations, reflecting the enduring relevance of his vision. Today, Kafka is celebrated as one of the most original and visionary writers of the 20th century, whose work continues to resonate across literature, philosophy, and political thought.

Here are some of Franz Kafka’s most memorable quotes:

Don’t bend; don’t water it down; don’t try to make it logical; don’t edit your own soul according to the fashion. Rather, follow your most intense obsessions mercilessly.

All language is but a poor translation.

Many a book is like a key to unknown chambers within the castle of one’s own self.

A non-writing writer is a monster courting insanity.

By believing passionately in something that still does not exist, we create it. The nonexistent is whatever we have not sufficiently desired.

Writing is utter solitude, the descent into the cold abyss of oneself.

A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us.

He is terribly afraid of dying because he hasn’t yet lived.

Youth is happy because it has the capacity to see beauty. Anyone who keeps the ability to see beauty never grows old.

Paths are made by walking.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of Scottish novelist, poet, essayist, and travel writer Robert Louis Stevenson, best known for his classic adventure novels, Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which have become enduring literary landmarks. A master storyteller, he also wrote poetry, travel essays, and children’s verse. Despite chronic illness, he traveled widely and spent his later years in Samoa, where he became beloved by the local people and continued writing prolifically. His ability to blend psychological insight with thrilling narratives remains his greatest literary achievement.

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson was born in 1850 in Edinburgh, Scotland. He was an only child. His father was a renowned civil engineer who specialized in designing lighthouses and played a pivotal role in enhancing maritime safety along the Scottish coast. His mother came from a family of lawyers and ministers and was known for her intelligence and strong religious faith. Together, they provided Robert with a well-educated, spiritually grounded upbringing.

From infancy, Stevenson was plagued by chronic lung illness, which left him bedridden for long periods and deeply shaped his imaginative inner life. During this time, he was cared for by his devoted nurse, who read him Bible stories and Scottish legends, nurturing his love for storytelling. Although Stevenson was frail and often ill as a child, he had a vivid imagination. He was sensitive, introspective, and precociously creative, often dictating stories before he could write.

As Stevenson grew older, he continued to struggle with poor health, which kept him out of school for long stretches and led to a largely home-based education. He developed a passion for reading, writing, and storytelling, encouraged by both his nurse and his parents. His family began to travel more frequently for health reasons, exposing him to new places and ideas. Stevenson started writing early essays and stories, laying the groundwork for his lifelong literary pursuits.

When Stevenson entered his teenage years, he began formal schooling at Edinburgh Academy, later enrolling at Edinburgh University in 1867 to study engineering, following in his family’s tradition. However, he showed little interest in engineering and was more drawn to literature, bohemian life, and radical ideas, which caused tension with his strictly religious father. During this time, Stevenson began publishing essays and experimenting with different literary styles, marking the beginning of his conscious pursuit of a writing career.

Around 1870, Stevenson officially abandoned engineering and switched to studying law at Edinburgh University, though his true passion remained writing. He became deeply involved in literary and artistic circles, adopting a rebellious, bohemian lifestyle that clashed with his family’s conservative values. During this period, he published some of his first notable essays and travel writings, including An Inland Voyage, and began to establish a reputation as a promising literary talent. He also met Fanny Osbourne, an American woman who would later become his wife and a major influence on his life.

During the late 1870s and early 1880s, Stevenson’s literary career blossomed. He traveled extensively across Europe and to America, often in pursuit of better health, and deepened his relationship with Osbourne. In 1879, Stevenson traveled to Monterey, California, to reunite with Osbourne while she recovered from illness. He stayed in a boarding house — now preserved as the Stevenson House — where he wrote, reflected, and deepened the bond that would soon lead to their marriage. They married in 1880. Despite ongoing illness, Stevenson wrote prolifically, producing travel essays, short stories, and beginning work on longer fiction.

In the summer of 1881, Stevenson was staying in the Scottish Highlands with his family. One rainy day, to entertain his 12-year-old stepson, Stevenson sketched a rough map of an imaginary island — complete with mountains, coves, and a hidden treasure. This playful drawing became the seed for his book Treasure Island, which he began writing the next day. What started as a game soon evolved into one of the most iconic adventure novels in literary history. In 1883, Stevenson published Treasure Island, his first major literary success, which brought him widespread fame and established him as a leading writer of adventure fiction.

During the mid to late 1880s, Stevenson reached the height of his literary fame while continuing to battle serious health issues. In 1885, Stevenson wrote A Child’s Garden of Verses, drawing inspiration from his often-bedridden childhood and the imaginative inner world he cultivated during those years. The collection captures the joys, fears, dreams, and wonder of childhood through simple yet lyrical poems that celebrate play, nature, solitude, and the boundless creativity of a child’s mind. After this, Stevenson published several major works, including The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and Kidnapped in 1886, and The Master of Ballantrae in 1889.

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a personal favorite of mine, is a novella about a respected scientist, Dr. Jekyll, who creates a potion that transforms him into the sinister and uninhibited Mr. Hyde, allowing him to act without moral restraint. The story explores the duality of human nature — the struggle between our higher, civilized self and our darker, instinctual urges. This transformation through a chemical substance can be seen as an allegory for altered states of consciousness, echoing the disinhibiting effects of certain drugs or the psychological splitting experienced in psychedelic or dissociative states. Stevenson’s tale eerily anticipates modern discussions around the subconscious, shadow integration, and the power of mind-altering compounds to reveal hidden aspects of the self. The very genesis of the tale, like much of Stevenson’s work, emerged not from waking thought but from the rich, mysterious depths of his dream life.

Stevenson placed great importance on dreaming in his creative process, often crediting his “Brownies” — his term for dreamlike subconscious helpers — for shaping his stories. He claimed that entire scenes and plots, including the core idea for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, came to him in dreams. Stevenson practiced a form of lucid dreaming, training himself to influence and recall dreams for creative inspiration. He saw dreaming as a vital portal to his imagination, a mysterious realm where his most original and compelling ideas emerged fully formed.

Seeking a climate more suitable for his fragile lungs and new inspiration for his writing, Stevenson and his family traveled the South Pacific in 1888. They set sail from San Francisco aboard the yacht Casco, and this journey marked the beginning of his deep engagement with the Pacific Islands, eventually leading to their settlement in Samoa in 1890. There, Stevenson became deeply involved in local life and politics, earning the affection of the Samoan people, who called him Tusitala, meaning “teller of tales.” This immersion in a new land and culture not only revitalized his body and imagination but also gently reshaped the contours of his inner life.

Stevenson’s spiritual perspective was complex and evolving. Raised in a strict Presbyterian household, he later questioned many aspects of organized religion, drifting toward a more personal, humanistic view of spirituality. Though often skeptical of dogma, he maintained a deep moral conscience, a reverence for mystery, and a profound empathy for human struggle and transformation — themes that appear throughout his writing. In his later years, especially in Samoa, his connection to nature, indigenous culture, and the rhythms of life deepened his spiritual outlook, blending Western skepticism with a quiet, heartfelt sense of wonder.

In Samoa, Stevenson continued writing with remarkable productivity despite his worsening health. He completed several works, including a sequel to Kidnapped titled Catriona, and he continued work on Weir of Hermiston, which many consider his most mature literary effort although he died before it was finished. Stevenson became an active voice in Samoan politics, advocating for native rights and earning deep respect from the local community.

In the final year of his life, Stevenson remained in Samoa, where he continued writing with passion and intensity despite ongoing health challenges. Stevenson stayed actively involved in local Samoan affairs, maintaining his role as an advocate and respected figure in the community. In 1894, while speaking to his wife, he collapsed from a sudden cerebral hemorrhage and died a few hours later at the young age of 44. The Samoan people honored him with a heartfelt ceremony and burial on Mount Vaea, fulfilling his wish to be laid to rest overlooking the sea.

Stevenson’s legacy endures as that of a masterful storyteller whose works have captivated generations and whose beloved stories blend adventure, psychological insight, and moral complexity. His influence extends beyond literature into popular culture, inspiring countless adaptations and interpretations. Despite lifelong illness, his prolific output, vivid imagination, and deep humanism left an indelible mark on both children’s and adult literature, securing his place among the greats of the English literary canon.

Here are some of Robert Louis Stevenson’s most memorable quotes:

Don’t judge each day by the harvest you reap but by the seeds that you plant.

Life is not a matter of holding good cards, but of playing a poor hand well.

I kept always two books in my pocket, one to read, one to write in.

The best things are nearest: breath in your nostrils, light in your eyes, flowers at your feet, duties at your hand, the path of God just before you. Then do not grasp at the stars, but do life’s plain common work as it comes certain that daily duties and daily bread are the sweetest things of life.

Everyone, at some time or another, sits down to a banquet of consequences.

There are no foreign lands. It is the traveler only who is foreign.

The saints are the sinners who keep on trying.

You can give without loving, but you can never love without giving.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of writer, humorist, and essayist Mark Twain, best known for his classic novels The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the latter often called the Great American Novel. Renowned for wit, satire, and keen social commentary, Twain became one of America’s most beloved writers and humorists. He was also a celebrated lecturer, riverboat pilot, and world traveler whose works captured the spirit, contradictions, and complexities of 19th-century America. Twain’s fearless critiques of racism, imperialism, and hypocrisy helped shape modern American literature and social thought.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (known by the pen name Mark Twain) was born in the small village of Florida, Missouri, in 1835 — just two weeks after Halley’s Comet passed by Earth, a celestial event he famously linked to both his birth and death. Twain’s father was a lawyer, judge, and storekeeper who struggled financially throughout his life. He was a stern, serious man with a strong belief in reason and order. Twain’s mother was warm, imaginative, and deeply religious, known for her wit and storytelling traits that greatly influenced her son’s humor and narrative voice. Together, their contrasting temperaments helped shape Twain’s unique blend of skepticism and sentimentality.

Twain was the sixth of seven children, though only three of his siblings survived childhood. When he was four years old, his family moved to the nearby town of Hannibal, a bustling port on the Mississippi River that would later serve as the model for the fictional town of St. Petersburg in his novels. These early years, shaped by frontier life, family struggles, and the vibrant river culture, deeply influenced the themes and settings of his later writing.

As a child, Twain was mischievous, curious, and full of imagination. He loved playing outdoors, exploring the Mississippi River, and getting into harmless trouble with other local boys — experiences that later inspired characters like Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn. Although he was often sickly in his early years, he developed a sharp sense of humor and a keen eye for human behavior, qualities that would define his writing.

In 1841, at age six, Twain began attending school in Hannibal, Missouri, a town deeply influenced by slavery and river commerce. His father died suddenly in 1847, when Twain was just eleven, plunging the family into financial hardship. That same year, Twain left school and began working as a printer’s apprentice to help support his family — an experience that introduced him to the world of print and storytelling, laying the groundwork for his future as a writer.

Twain continued working in the printing trade, becoming a typesetter for local newspapers, including his brother Orion’s publication. During this time, he began writing humorous sketches and gaining exposure to literature and journalism. He left Hannibal in his late teens, traveling to cities like St. Louis, New York, and Philadelphia to work in print shops and expand his horizons. These years broadened his experiences, deepened his interest in writing, and fueled his growing ambition to explore the wider world beyond Missouri.

In 1857, Twain began a transformative apprenticeship as a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi River — a prestigious and well-paying profession that deeply influenced his later writing. He earned his pilot’s license in 1859 and spent several years navigating the river, gaining firsthand knowledge of its culture and rhythms. This career came to an abrupt halt with the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, which shut down river traffic and led Twain to join a short-lived Confederate Militia before heading west to seek new opportunities.

After trying his luck at mining in Nevada with little success, he began working as a journalist for the Territorial Enterprise in Virginia City, where he adopted the pen name “Mark Twain.” His sharp wit and storytelling flair quickly earned him regional fame. In 1865, his humorous short story The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County was published and became a national sensation. Over the next few years, he traveled extensively, including a lecture tour and a journey to Europe and the Holy Land, which he chronicled in his bestselling 1869 travel book The Innocents Abroad.

Following the success of The Innocents Abroad, Twain continued his lecture tours and published several more works, including Roughing It in 1872, a humorous account of his adventures in the American West. In 1870, Twain married Olivia Langdon, and the couple settled in Hartford, Connecticut, where they started a family. During this period, Twain also began work on what would become his masterpiece, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, which was published in 1876 and drew deeply from his childhood in Hannibal. These years were both creatively productive and personally joyful, marking the beginning of Twain’s most celebrated literary era.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer became one of Twain’s most beloved works. He followed this with several other notable books, including A Tramp Abroad in 1880, a humorous travel memoir, and The Prince and the Pauper in 1881, his first foray into historical fiction. During this time, he continued to write and lecture while raising his children with Olivia in their Hartford home.

In 1883, Twain published Life on the Mississippi, a vivid memoir of his steamboat days that blended autobiography with history and humor. In 1884, he founded his own publishing company, Charles L. Webster & Co., which would go on to publish The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in 1885 — a novel now regarded as a cornerstone of American literature. Though the book received mixed reviews at first, it later gained acclaim for its bold exploration of race, freedom, and morality. Twain also published A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court in 1889, showcasing his growing interest in satire and social criticism.

In 1894, Twain’s publishing company went bankrupt, largely due to poor investments, including backing an ill-fated typesetting machine. To repay his debts, Twain embarked on an exhausting global lecture tour, earning admiration for his determination to honor his obligations despite not being legally required to do so. During this time, he also published The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson in 1894, a biting social satire on race and identity. Sadly, his daughter Susy died in 1896 at just 24 years old, a devastating loss that plunged Twain into deep grief.

One of the most famous anecdotes from Twain’s life occurred in 1897, when a newspaper mistakenly published his obituary. Upon hearing the news, Twain quipped in a letter from London, “The report of my death was an exaggeration.” The remark quickly became legendary and showcased his trademark wit. The incident not only amused the public but also cemented Twain’s reputation as a master of humorous commentary, even in the face of premature mortality.

That same year, Twain published Following the Equator, a travelogue inspired by his around-the-world lecture tour, which helped him gradually repay his debts in full by 1898. Though he regained financial stability and remained a celebrated public figure, Twain’s later writings grew darker in tone, reflecting his growing disillusionment with humanity and society. Tragedy struck again in 1903 when his beloved wife Olivia’s health declined severely, prompting the family to move to Italy in hopes of her recovery.

In 1904, Twain’s wife Olivia died, deepening his sorrow and further darkening the tone of his later writings. Despite his grief, he remained a prominent public figure, delivering speeches and receiving widespread honors, including an honorary doctorate from Oxford University in 1907. He continued to write essays and autobiographical pieces, often filled with biting satire and cynicism. Tragically, in 1909, his youngest daughter, Jean, died suddenly of a seizure, compounding the heartbreak that marked his final years. These personal losses, along with the disillusionments of old age, profoundly shaped his spiritual outlook and deepened the philosophical questions that permeated his later work.

Twain’s spiritual perspective was complex and evolved throughout his life. Though raised in a religious environment, he grew increasingly skeptical of organized religion and questioned conventional beliefs about God, morality, and the afterlife. He often expressed agnostic or even atheistic views, especially in his later writings, where he critiqued religious hypocrisy and the idea of a benevolent deity amid human suffering. Yet beneath his satire and cynicism lay a deep moral concern for justice, compassion, and truth, suggesting a kind of spiritual conscience rooted more in human empathy than in dogma.

In the final year of his life, Twain was in declining health and deeply affected by the recent loss of his daughter. Despite his physical and emotional exhaustion, he remained intellectually active, continuing work on his autobiography and reflecting on mortality with characteristic wit and melancholy. Twain died in 1910 at the age of 74 in Redding, Connecticut, just as Halley’s Comet returned, as he had famously predicted years earlier. His passing marked the end of a remarkable life that had profoundly shaped American literature and culture.

Twain’s legacy endures as one of the most influential voices in American literature. Celebrated for his sharp wit, vivid storytelling, and fearless social critique, he captured the complexities of American life with unmatched humor and humanity. His novels remain foundational texts, both for their literary brilliance and their exploration of race, morality, and freedom. Twain’s voice still resonates today, not just as a humorist and satirist, but as a keen observer of the human condition.

Twain’s literary influence extended far beyond his era. Influential author Ernest Hemingway famously said that “all modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn.” Twain was praised by celebrated novelist William Faulkner as the “greatest humorist the United States has produced,” calling him “the father of American literature.” Our late friend, the legendary psychologist Timothy Leary, was also a big fan of Twain. When I took a workshop with Tim at the Esalen Institute in 1983, which led to my meeting Carolyn, Tim was working on an interactive version of Twain’s book, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Some of the quotes that Mark Twain is known for include:

I have never let my schooling interfere with my education.

The fear of death follows from the fear of life. A man who lives fully is prepared to die at any time.

Keep away from people who try to belittle your ambitions. Small people always do that, but the really great make you feel that you, too, can become great.

In a good book room, you feel in some mysterious way that you are absorbing the wisdom contained in all the books through your skin, without even opening them.

Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it is time to pause and reflect.

The man who does not read has no advantage over the man who cannot read.

I do not fear death. I had been dead for billions and billions of years before I was born, and had not suffered the slightest inconvenience from it.

Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth isn’t.

Carolyn and I have long admired the work of Michelangelo — Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet — who was a towering figure of the Renaissance and is celebrated as one of history’s greatest artists. Renowned for his masterful sculptures, David and Pietà, he also painted the awe-inspiring ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, which remains one of the crowning achievements of Western art. Michelangelo helped shape the course of art and architecture for centuries, notably designing the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. His genius left an indelible mark on the world, merging divine beauty with human form. With renewed global attention on the Vatican following the election of the new pope, Michelangelo’s enduring presence in St. Peter’s Basilica and the Sistine Chapel reminds us of how deeply his art continues to shape the spiritual and cultural heart of the Catholic world.

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni was born in 1475 in Caprese, a small town within the Republic of Florence — a powerful medieval and early modern state whose capital was the city of Florence, in Tuscany, Italy. Michelangelo’s father was a minor Florentine official from a once-prominent but declining noble family. He held occasional government posts, such as magistrate or local administrator, but struggled financially and never achieved lasting success. His mother came from a similarly respectable background but died when Michelangelo was six years old. Despite their noble lineage, Michelangelo’s parents were not wealthy, and his father initially disapproved of his artistic ambitions, viewing them as beneath the family’s social standing.

After Michelangelo’s mother became ill and died, he was sent to live with a wet nurse in the nearby town of Settignano, where her family worked as stonecutters. Growing up in this environment, surrounded by marble and chisels, likely planted the earliest seeds of his sculptural genius. As a child, Michelangelo was sensitive, intelligent, and deeply drawn to art, often preferring sketching and observing nature over traditional studies. He was known to be somewhat aloof and introspective, with a fierce independence and strong will that sometimes clashed with his family’s expectations. Even at a young age, he displayed remarkable artistic talent, and by the time he was a teenager, his skills in drawing and sculpture were apparent.

During the early 1480s, Michelangelo attended the Latin school of Francesco da Urbino, though he showed little interest in traditional education. Instead, he spent much time copying drawings and visiting churches to study frescoes. In 1487, at just twelve years old, he was apprenticed to the painter Domenico Ghirlandaio, marking the official beginning of his artistic training in one of Florence’s leading workshops.

After a brief apprenticeship with Ghirlandaio, Michelangelo was recommended to the Medici family and, by 1490, was studying at the Medici-sponsored sculpture garden under the guidance of Bertoldo di Giovanni. There, he gained exposure to classical antiquities and mingled with Florence’s intellectual elite, including Lorenzo de’ Medici, who became his patron. During this time, Michelangelo sculpted some of his early masterpieces, such as the Battle of the Centaurs. However, after Lorenzo died in 1492 and rising political unrest in Florence, Michelangelo left the Medici court. By 1494, with tensions escalating under Savonarola’s influence, he departed Florence for Bologna, seeking refuge and continuing his artistic development.

In 1496, at just 21 years old, Michelangelo sculpted a marble Cupid and, at the suggestion of a dealer, artificially aged it to appear ancient. The sculpture was sold to Cardinal Riario of San Giorgio in Rome, who later discovered the deception. Rather than being outraged, the Cardinal was so impressed by Michelangelo’s skill that he invited the young artist to Rome — an invitation that launched his rise to fame.

Michelangelo traveled to Rome, where he created the Bacchus, a sensuous marble statue that impressed Roman patrons. His breakthrough came in 1498 when he was commissioned to sculpt the Pietà for St. Peter’s Basilica — an extraordinary work that blended delicate emotion with technical brilliance. In 1501, Michelangelo returned to Florence and received the commission for what would become one of his most iconic masterpieces: the colossal marble statue of David, which was completed in 1504 and instantly hailed as a symbol of civic pride and artistic genius.

Michelangelo then began work on the Battle of Cascina fresco, though it remained unfinished. In 1505, Pope Julius II summoned him to Rome to design a grandiose tomb, a project plagued by delays and complications. Tensions with the Pope led Michelangelo to briefly flee Rome, but in 1508 he was called back — this time to begin one of the most ambitious artistic feats in history: painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, the large papal chapel built within the Vatican between 1477 and 1480.

Michelangelo became immersed in the monumental task of painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling, a commission that would define his legacy. Working largely alone under grueling conditions, he completed the frescoes in 1512, unveiling a breathtaking vision of biblical scenes — from the Creation of Adam to the prophets and sibyls — that stunned the world and redefined Renaissance art. Following this triumph, he returned briefly to work on Pope Julius II’s tomb and created the powerful Moses statue.

In 1513, after Julius’s death, Pope Leo X, a member of the powerful Medici family, known for their wealth and patronage of the arts, came to power, and Michelangelo shifted focus to new architectural and sculptural projects. Under the patronage of the new pope, Michelangelo was tasked with designing the façade of the Church of San Lorenzo, but despite years of planning and sourcing marble from the quarries at Carrara, the project was ultimately abandoned due to funding and political complications. During this time, he also began work on the Medici Chapel, intended as a grand mausoleum for his patrons. Though progress was slow and frequently interrupted, this period marked a deepening of his architectural vision and further solidified his role as both a sculptor and architect of major importance.

Michelangelo worked intensively on the Medici Chapel in Florence, crafting striking tomb sculptures like Night and Day and Dawn and Dusk, which blended spiritual symbolism with anatomical mastery. In 1527, political upheaval shook Florence when the Medici were temporarily overthrown and the city became a republic. Michelangelo, a supporter of the republic, was appointed chief of fortifications and oversaw the city’s defenses against the impending siege by Medici and imperial forces. This marked a rare period where the artist became directly involved in military engineering, blending creativity with civic duty during a time of political crisis.

After the fall of the Florentine Republic in 1530 and the return of Medici rule, Michelangelo was briefly out of favor and feared retribution for his role in defending the republic. However, thanks to powerful allies and his immense reputation, he was pardoned and allowed to continue his work. He resumed and advanced the Medici Chapel and also began work on the Laurentian Library, designing its striking staircase and innovative architectural features. During this period, Michelangelo’s artistic focus began shifting increasingly toward architecture, and his work grew more spiritually introspective and monumental in tone.

Michelangelo held a deeply personal and evolving spiritual perspective, rooted in his Catholic faith yet infused with a profound sense of inner struggle and longing for divine truth. He believed that art was a path to God, a sacred act of revealing the divine through the beauty of the human form. In his later years, his work and poetry became increasingly contemplative, expressing remorse, humility, and a yearning for spiritual salvation. For Michelangelo, the creative act was both a gift from God and a form of worship— a means of sculpting the soul toward grace.

Michelangelo deepened his work in both sculpture and architecture while continuing to navigate shifting political and religious tides. He remained in Florence for part of this time, refining the Medici Chapel and Laurentian Library, though progress was slow due to interruptions and conflicts. In 1534, following the death of his beloved friend and muse Vittoria Colonna and amid growing tensions in Florence, Michelangelo left the city for good and settled permanently in Rome. There, Pope Paul III commissioned him to paint The Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel — a vast and emotionally charged fresco that he began in 1536 and completed in 1541, unveiling a work of awe, fear, and divine reckoning that stunned the world and cemented his spiritual and artistic legacy.

During the late 1540s, Michelangelo’s focus shifted increasingly toward architecture and religious devotion. He continued working under Pope Paul III and was appointed chief architect of St. Peter’s Basilica in 1546, a role he accepted reluctantly but would hold for the rest of his life. Michelangelo reimagined the basilica’s design with bold, unified forms, laying the groundwork for its majestic dome. During this time, he also worked on the Capitoline Hill redesign and created deeply personal sculptures like the Florentine Pietà, reflecting his preoccupation with mortality and faith in his later years.

During the 1550s, Michelangelo remained in Rome, dedicating himself almost entirely to architecture and religious art in his final decades. He continued refining the design and construction of St. Peter’s Basilica, focusing on the great dome and simplifying the plans to emphasize harmony and grandeur. He also worked on the Porta Pia and the Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri, transforming ancient Roman ruins into a Christian church. Despite his age, he remained fiercely productive, driven by spiritual conviction, and developed increasingly abstract and emotionally intense sculptural works, many of which he never completed. These years reflect a period of profound introspection and enduring creative power.

During the early 1560s, Michelangelo, now in his 80s, continued to work with remarkable dedication, primarily overseeing the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. He devoted himself to perfecting the design of its massive dome, which would become one of the most iconic architectural achievements in history. During these years, his art grew increasingly introspective and spiritual, as seen in his unfinished sculptures like the Rondanini Pietà, a raw and poignant reflection on suffering and mortality. Though he rarely left his home, Michelangelo remained an influential cultural figure, corresponding with artists and thinkers, and in 1563, he was named honorary president of the newly founded Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence, recognizing his unparalleled contributions to art and architecture.

In the final year of his life, Michelangelo remained mentally sharp and spiritually reflective. He continued to advise on the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica until just days before his death, and worked intermittently on the Rondanini Pietà. Michelangelo died in 1564, at the age of 88, in Rome. Honoring his wishes, his body was secretly transported to Florence, where he was buried with great ceremony at the Basilica of Santa Croce. Revered as a divine genius even in his lifetime, Michelangelo’s death marked the end of an era, but his legacy would shape Western art for centuries to come.

Michelangelo’s legacy is that of a visionary who redefined the boundaries of art, architecture, and human creativity. His masterpieces — such as David, the Pietà, the Sistine Chapel ceiling, and the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica— remain among the most celebrated works in Western history, exemplifying both technical brilliance and profound emotional depth. As a sculptor, painter, architect, and poet, he embodied the Renaissance ideal of the universal genius, and his influence echoes through centuries of artists who followed. Michelangelo’s work continues to inspire awe, not only for its beauty and skill, but for its spiritual intensity and enduring quest to capture the divine within the human form.

Some of the quotes that Michelangelo is known for include:

If people knew how hard I had to work to gain my mastery, it would not seem so wonderful at all.

The greatest danger for most of us is not that our aim is too high and we miss it, but that it is too low and we reach it.

If you knew how much work went into it, you wouldn’t call it genius.

Genius is eternal patience.

I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.

The sculpture is already complete within the marble block, before I start my work. It is already there, I just have to chisel away the superfluous material.

Lord, grant that I may always desire more than I accomplish.

Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.

The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection.

Carolyn and I have long appreciated the work of French author, poet, playwright, and politician Victor Hugo, who is considered one of France’s greatest writers, celebrated for his epic novels Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, which brought attention to social injustice and the plight of the marginalized. He was also a powerful poet, dramatist, and political figure who championed human rights, abolition of the death penalty, and democratic ideals. Exiled for opposing Napoleon III, Hugo became a symbol of resistance and moral conscience, and his legacy helped shape French literature, politics, and culture.

Victor-Marie Hugo was born in Besancon, France, in 1802. Hugo’s father was a high-ranking officer in Napoleon’s army who rose to the rank of general and was often stationed abroad. His mother was a staunch Royalist with literary interests, who managed the household and strongly influenced Victor’s early upbringing, especially during his father’s long absences. Their opposing political views created tension, and his mother eventually separated from Hugo’s father, raising Victor primarily on her own.

Hugo was sensitive, observant, and highly imaginative as a child, often lost in books and daydreams. He showed precocious writing talent and began composing poetry at an early age. Despite the instability caused by his parents’ strained relationship and frequent moves, he developed a deep inner world and a strong moral sense that would later shape his literary voice.

During these early years, Hugo lived primarily in Paris with his mother after she separated from his father, though he also spent time in Avellino, Italy, where his father was stationed. In 1811, at age nine, Hugo entered the prestigious Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris, beginning a rigorous classical education that sharpened his literary talents. In 1819, he won a prestigious poetry prize from the Académie des Jeux Floraux for an unpublished poem— one of his earliest public recognitions, marking him as a rising literary talent.

During this time, Hugo grew close to Adèle Foucher, his childhood friend, with whom he began a secret romantic correspondence. Hugo’s world changed profoundly in 1821 when his beloved mother died; this loss both devastated him and gave him the freedom to pursue his relationship with Adèle more openly. That same year, he and his brothers launched a royalist literary journal, Le Conservateur Littéraire, marking the start of his public literary career.

In 1822, Hugo married Foucher, fulfilling a long-held romance, and published his first book of poetry, Odes and Various Poems, which earned him a royal pension from King Louis XVIII. Hugo quickly rose to prominence in the Romantic movement, and in 1827, even though his play Cromwell wasn’t performed, its bold introduction stirred public attention by laying out the key ideas of Romantic literature. Due to its length and the logistical challenges of staging such a large cast of characters, the play remained unperformed until 1956.

During this period, Hugo had several children and began experimenting with novel-writing. In 1830, his play “Hernani” premiered at the Comédie-Française, igniting a cultural battle between Classicists and Romantics and marking a decisive victory for the Romantic movement. In 1831, he published his novel The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, which became a literary sensation and helped spark interest in preserving Gothic architecture. During this time, Hugo’s household became more complicated as he and his wife both began having extramarital affairs.

Historical records and Hugo’s journals suggest that for many years, Hugo regularly visited and financially supported several sex workers, most notably a woman named Léonie d’Aunet, who was also his longtime mistress and a writer herself. While married to Foucher, Hugo maintained numerous extramarital relationships, often visiting prostitutes in Paris and even documenting these encounters in private notebooks with coded symbols and numbers. His writings reveal a complex, often romanticized view of these women, reflecting both a genuine emotional involvement and the era’s patriarchal attitudes.

During the late 1830s, Hugo continued to gain literary prestige while also becoming more engaged in public life. He published several successful works, including the novel The Sea Devils and another poetry collection in 1837. He was elected to the Académie Française in 1841, a major honor solidifying his place in the French literary elite after years of rejection. Around this time, he also began to turn his attention toward politics and social issues, laying the groundwork for his later political activism. These years marked a transition from celebrated writer to national public figure.

In 1843, Hugo’s beloved daughter Léopoldine drowned in a boating accident, a loss that devastated him and led to a period of deep mourning and creative silence. Emerging from grief, he increasingly turned toward politics, becoming a vocal advocate for social reform. In 1845, Hugo was appointed to the Chamber of Peers by King Louis-Philippe, and by 1848, during the revolution that established the Second Republic, he was elected to the National Assembly.

During the early 1850s, Hugo became an outspoken critic of authoritarianism and entered into exile. After fiercely opposing Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte’s 1851 coup d’état and the rise of the Second Empire, Hugo was forced to flee France, beginning a long period of exile on the islands of Jersey and then Guernsey. Despite being cut off from his homeland, he remained politically active through his writing — publishing Napoléon le Petit in 1852 and Les Châtiments in 1853, both scathing critiques of the regime. This period also marked a creative renaissance, as he began working on Les Misérables and solidified his role as a moral voice for justice and liberty from afar.

In 1862, Hugo completed and published his magnum opus Les Misérables, after over a decade of work. Les Misérables is a sweeping tale of redemption, justice, and compassion that follows ex-convict Jean Valjean’s journey to rebuild his life while being relentlessly pursued by the law amid the social struggles of 19th-century France. The novel was an immediate international success and solidified his status as a literary and moral authority. During this time, he also published La Légende des Siècles in 1859, an ambitious poetic chronicle of humanity’s spiritual evolution, and Les Contemplations in 1856, which mourned his daughter Léopoldine.

Hugo’s spiritual perspective was deeply humanistic, mystical, and evolving. Though raised Catholic, he grew disillusioned with organized religion and embraced a personal, expansive sense of the divine— believing in God, the soul’s immortality, and a moral universe guided by justice and love. He saw the human spirit as on a journey toward enlightenment, often expressing faith in progress, compassion, and the triumph of conscience. His writings reflect a profound reverence for the mystery of existence, blending spiritual idealism with a passionate call for social and moral transformation.

In 1862, shortly after the publication of Les Misérables, Hugo was curious about the public’s reception of his monumental novel, and he sent his publisher a letter consisting of a single character: “?”. In response, the publisher sent back an equally terse reply: “!”. This brief but iconic exchange is said to be the shortest correspondence in history and reflects both Hugo’s wit and the instant success of his masterpiece.

During the 1860s, Hugo continued his exile on Guernsey, producing a steady stream of literary and political works that deepened his reputation as a prophetic voice of conscience. Although still barred from France, his fame only grew, and he remained a vocal critic of Napoleon III’s regime. In 1870, with the fall of the Second Empire following the Franco-Prussian War, Hugo triumphantly returned to Paris, where he was welcomed as a national hero.

Hugo reestablished himself in France and remained a towering public figure during the early years of the Third Republic. In 1871, he briefly served as a senator and defended the Paris Commune, though he was critical of its violence. He published politically charged works, reflecting on the trauma of war and civil strife. During these years, Hugo endured personal losses— the deaths of his son Charles in 1871 and his other son François-Victor in 1873 — but continued writing, releasing The Legend of the Ages and The Art of Being a Grandfather, expressing both sorrow and a tender love for his grandchildren. Despite his grief, he remained a revered symbol of resilience and humanist ideals.

During the early 1880s, Hugo’s health began to decline. In 1878, he suffered a mild stroke, which limited his public activity, though he continued writing, working on his poetry collection The Four Winds of the Mind, which was published in 1881. Hugo was celebrated across France on his 80th birthday in 1882, drawing massive public admiration. Despite personal frailty, Hugo lived to see his ideas widely embraced, embodying the moral conscience of France in his final years.

In the final year of his life, Hugo was gravely ill and largely bedridden, yet he remained a revered symbol of the French Republic and a moral beacon to the public. As his health declined, crowds gathered daily outside his Paris home to pay tribute. He died in 1885, at the age of 83. Hugo’s death prompted a national outpouring of grief, and he was given a state funeral attended by over two million people. Hugo was buried in the Panthéon, alongside other great figures of French history, cementing his legacy as a literary giant and champion of justice.

Hugo’s legacy is that of a towering literary genius and a fearless advocate for justice, freedom, and human dignity. His novels, especially Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, continue to resonate worldwide for their emotional power and social conscience. As a poet, playwright, and political thinker, he helped shape the Romantic movement and championed causes like the abolition of the death penalty and the defense of the poor and oppressed. Revered in his lifetime and ever since, Hugo remains a symbol of moral courage and artistic brilliance whose work transcends time and borders.

Hugo’s Les Misérables has experienced renewed success in recent years through both stage and screen adaptations. The 2012 film adaptation, directed by Tom Hooper, achieved significant acclaim and won three Academy Awards. On stage, Les Misérables continues to captivate audiences globally. The musical’s enduring popularity is evident in its ongoing tours and revivals. These adaptations underscore the lasting impact of Hugo’s narrative, resonating with contemporary audiences through powerful performances and innovative presentations.

Here are some of Victor Hugo’s most beloved and enduring quotes, which capture the soul of his thought:

Music expresses that which cannot be put into words and that which cannot remain silent.

A garden to walk in and immensity to dream in— what more could he ask for? A few flowers at his feet and above him the stars.

Even the darkest night will end and the sun will rise.

It is nothing to die. It is frightful not to live.

Laughter is sunshine, it chases winter from the human face.

Certain thoughts are prayers. There are moments when, whatever be the attitude of the body, the soul is on its knees

To love or have loved, that is enough. Ask nothing further. There is no other pearl to be found in the dark folds of life.

Those who do not weep, do not see.

To love another person is to see the face of God.

Victor Hugo’s vision still invites us to dream of a more just, compassionate world — one in which, even after the darkest night, the sun still rises.

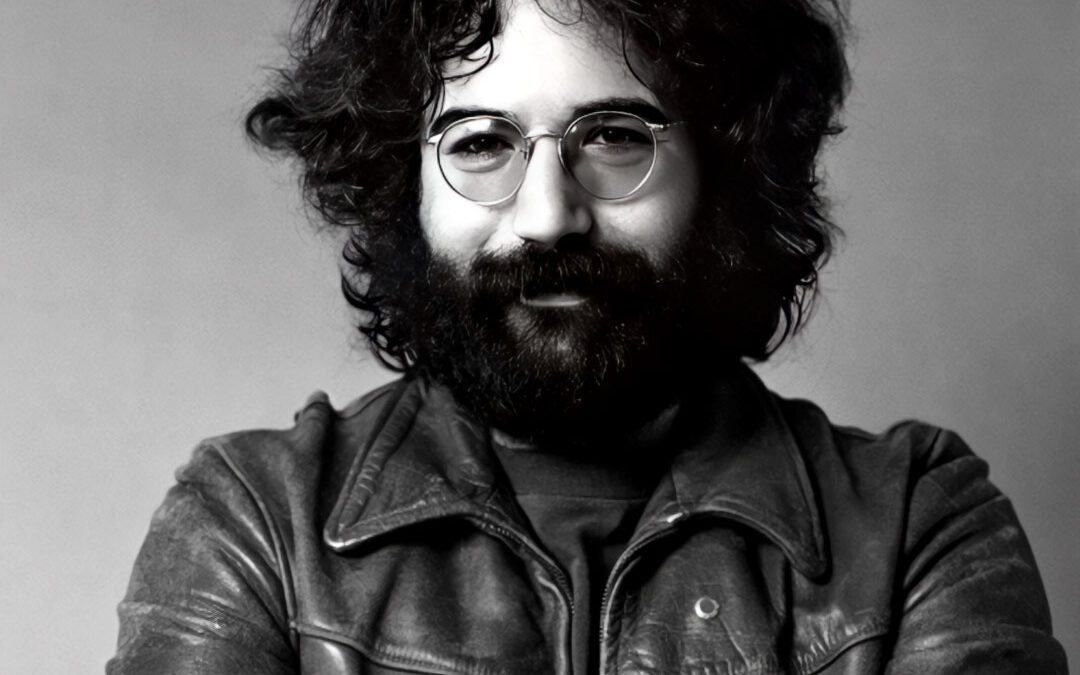

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of musician, singer, and songwriter Jerry Garcia, best known as the lead guitarist and vocalist for The Grateful Dead, one of the most influential and enduring bands in rock history. With his distinctive improvisational guitar style and eclectic musical influences— ranging from bluegrass and folk to jazz and psychedelic rock — Garcia helped pioneer the countercultural sound of the 1960s. Garcia’s live performances with The Grateful Dead became the stuff of legend, defining an era of improvisational rock and fostering an unparalleled concert experience.

Over their 30-year career, The Grateful Dead played more than 2,300 concerts, the most of any band in history at the time. Their shows drew millions of fans, with some estimates suggesting that more than 25 million people attended their concerts. Beyond The Grateful Dead Garcia collaborated on numerous side projects, including the Jerry Garcia Band, and contributed to a wide array of musical recordings. A cultural icon, Garcia’s artistry and free-spirited philosophy left an indelible mark on generations of musicians and fans.

Jerome John Garcia was born in 1942 in San Francisco, California. Both of his parents had strong ties to music and the arts. His father was a Spanish immigrant who worked as a Jazz musician and owned a tavern in San Francisco. He played woodwind instruments, particularly the clarinet and saxophone, and was part of a swing band. His mother was a native Californian who took over managing the family tavern after her husband died in 1947. She was independent and strong-willed, later working as a nurse. His mother also had a deep appreciation for music, which she passed down to Jerry, encouraging his artistic interests from a young age.

Garcia’s father drowned while fishing when Garcia was only five, leaving his mother to raise him and his older brother. That same year, Garcia suffered another life-altering event when he accidentally lost two-thirds of his right middle finger in a wood-chopping accident in the Santa Cruz Mountains, an injury that would later shape his distinctive guitar-playing style. Despite these hardships, his early years were filled with artistic and musical exposure, as his mother encouraged his creativity, and he developed an early love for the guitar.

As a child, Garcia was artistic, imaginative, and somewhat rebellious. He had a deep love for drawing and storytelling, often spending hours sketching and immersing himself in comic books and science fiction. Despite his early exposure to music, he initially showed more interest in visual arts than in playing instruments. He was also known for his mischievous streak, sometimes getting into trouble at school and struggling with authority. Garcia adapted quickly to losing part of his finger and didn’t let it hinder his creativity. His mother described him as a dreamer, and even as a young boy, he had an unconventional, free-spirited nature that foreshadowed his future as a countercultural icon.

Garcia was largely raised by his grandparents and older brother. In 1950, his mother enrolled him in an art school, nurturing his passion for drawing and creativity. However, Garcia was a restless and rebellious student, often struggling in structured environments. In 1953, at the age of 11, his mother moved the family to Menlo Park, California, where he was first introduced to rhythm and blues and early rock ‘n’ roll through the radio and his older brother’s record collection. Around this time, he also started experimenting with the banjo and guitar, marking the beginning of his lifelong relationship with stringed instruments.

In 1957, Garcia’s older brother introduced him to rock and roll, sparking his love for the electric guitar. Around this time, he discovered Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley, whose music greatly influenced his playing style. In 1959, Garcia dropped out of high school and briefly attended the San Francisco Art Institute before joining the U.S. Army— though his rebellious nature led to a discharge after just nine months. After leaving the military in 1960, he drifted through Northern California, living a bohemian lifestyle and immersing himself in folk and bluegrass music.

A major turning point came in 1961 when a near-fatal car accident left him determined to dedicate his life to music. Garcia and several friends were driving through the Santa Cruz Mountains when the driver lost control, causing the car to flip. One of his friends died in the crash, but Garcia miraculously survived. Shaken by the experience, he later described it as a “wake-up call,” realizing that he wanted to dedicate his life to playing music rather than drifting aimlessly. This pivotal moment set him on the path toward becoming one of the most legendary musicians of all time. That same year, he met Robert Hunter, his future songwriting partner, and he began performing in coffeehouses.

Garcia began playing bluegrass and folk music in the Palo Alto area, forming the band Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions with Ron “Pigpen” McKernan and Bob Weir. By 1965, inspired by the rising psychedelic movement, the group evolved into The Warlocks and was later renamed The Grateful Dead. By 1966, The Grateful Dead became central to author Ken Kesey’s legendary Acid Tests, blending psychedelic rock with improvisational jamming in environments where psychedelics were consumed.

Psychedelics played a profound role in shaping Garcia’s creativity, philosophy, and musical approach. His early experiences with LSD expanded his perception of reality and deeply influenced his improvisational style, allowing him to approach music as a fluid, ever-evolving conversation. Psychedelics also reinforced his free-spirited philosophy, emphasizing the importance of play, spontaneity, and interconnectedness, both in life and on stage. He saw The Grateful Dead performances as shared psychedelic experiences, where music became a vehicle for exploration, transformation, and collective consciousness.

As the San Francisco counterculture movement flourished, The Grateful Deadsigned with Warner Bros. Records and released their self-titled debut album in 1967. Their live performances, particularly at events like the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, solidified their reputation as pioneers of psychedelic rock. By 1968, they were expanding their musical range, incorporating jazz and experimental elements.

The Grateful Deadwas known for its extended, free-flowing jams, unpredictable setlists, and deep connection with its audience, earning a devoted fanbase known as Deadheads. The band’s ability to create a unique, ephemeral musical experience at every show made their live performances an essential part of their legacy. In 1969, Garcia and The Grateful Dead performed at Woodstock, further cementing their role in the counterculture movement. That same year, they released Live/Dead, their first live album, which captured their legendary improvisational style. In 1970, they reached new heights with the release of Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty, albums that introduced a folk and country influence, including classics like Truckin’ and Casey Jones.

Throughout the early ’70s, Garcia also explored side projects, forming the Jerry Garcia Band and collaborating with other musicians. By 1972, after the passing of founding member Pigpen, the band continued evolving musically, culminating in their 1972 European tour and live album. In 1973, they released Wake of the Flood, the first album on their independent label, Grateful Dead Records. However, in 1974, the band temporarily took a break from touring, partly due to the physical and financial toll of their massive Wall of Sound speaker system experiment. Despite this, Garcia remained musically active, releasing solo albums and continuing to refine his eclectic style before The Grateful Deadreturned in 1976.

In 1971, our friend psychologist Stanley Krippner conducted a telepathy experiment at a Grateful Dead concert at the Capitol Theatre in Port Chester, New York. The experiment aimed to test whether telepathic communication could occur between the band’s audience and a designated “receiver” in a sleep lab. While the Grateful Dead played, members of the audience were shown a series of randomly selected images on a screen and were instructed to mentally “send” these images to a sleeping subject at the Maimonides Medical Center Dream Laboratory in Brooklyn. Later, when the receiver’s dreams were analyzed, some notable correspondences emerged between the dream imagery and the projected pictures, suggesting possible extrasensory perception. Though not conclusive, the study remains one of the most fascinating intersections of parapsychology, music, and consciousness research, reflecting both Krippner’s and the Grateful Dead’s interest in mind expansion and the nature of reality.

In 1976, Garcia and The Grateful Dead resumed touring with a refined, jazz-influenced sound, and in 1977, they released Terrapin Station, featuring the epic title track that became a fan favorite. The late ’70s saw some of their most acclaimed live performances. During this period, Garcia also expanded his solo work, releasing Cats Under the Stars in 1978 with the Jerry Garcia Band, which he later called his favorite personal project. However, by the early 1980s, Garcia’s heroin addiction and declining health began affecting his performance.

In 1986, Garcia fell into a diabetic coma, nearly dying. After awakening, he had to relearn how to play the guitar, but the experience revitalized his passion for music. By 1987, The Grateful Deadexperienced an unexpected commercial breakthrough with In the Dark, which featured the song Touch of Grey, their only Top 10 hit. The album’s success introduced the band to a new generation of fans, leading to sold-out stadium tours.

The Grateful Dead remained one of the highest-grossing touring acts, playing massive stadium shows and embracing new technology, including MIDI guitars to expand their sound. Garcia also rekindled his love for acoustic music, collaborating with David Grisman on several projects. However, his health deteriorated due to diabetes, weight gain, and ongoing substance abuse. In 1992, Garcia was hospitalized and forced to take a break from touring, but he returned the following year despite continuing struggles. As his health struggles intensified, Garcia’s outlook on life and music remained deeply influenced by his spiritual philosophy, which had long been intertwined with his artistic journey.

Garcia had a fluid and open-ended spiritual perspective, shaped by psychedelics, Eastern philosophy, and the countercultural ethos of the 1960s. He was fascinated by mysticism, the nature of consciousness, and the interconnectedness of all things, often expressing a belief in cosmic playfulness and improvisation as guiding forces in life and music. Though he wasn’t formally religious, he was deeply influenced by Buddhism, the Tao Te Ching, and the transcendental aspects of Grateful Dead performances, which he saw as a kind of collective spiritual experience shared with the audience.

Garcia’s health continued to decline, but despite this, he toured with The Grateful Dead through the summer, though his performances were often frail and inconsistent. Seeking recovery, Garcia checked into the Serenity Knolls treatment center in Forest Knolls, California, in 1995. Just days after entering rehab, he passed away in his sleep from a heart attack at the age of 53.

Garcia’s legacy extends far beyond his role as The Grateful Dead’s frontman— he became a cultural icon, embodying the spirit of musical exploration and countercultural freedom. His improvisational guitar style and genre-blending approach influenced countless musicians, while his work with The Grateful Dead helped pioneer the modern jam band movement. Beyond music, he left an impact through his artwork, humanitarian efforts, and the enduring community of Deadheads who continue to celebrate his music. Even after his passing, his influence remains alive through tribute bands, festivals, and a continued appreciation for his visionary approach to sound and storytelling.

The Grateful Dead released a total of 13 studio albums and 10 live albums during their active years, along with numerous archival releases after Garcia’s passing. While their studio albums were well-received, it was their live recordings that truly captured the essence of their improvisational spirit and kept their fanbase engaged. Commercially, The Grateful Dead achieved gold and platinum status multiple times, and the band’s total album sales exceeded 35 million worldwide.

I attended two live Grateful Dead shows in the late 1980s, and one performance of the Jerry Garcia Band. In 1993, Jerry wrote a quote for the back cover of my book Mavericks of the Mind (which was recently published in its third edition and contains an interview with Carolyn). In 1994, I interviewed Jerry for my book Voices from the Edge. It was an amazing experience for Rebecca Novick and me to have 3 hours alone with Jerry after we overheard his publicist turning down an interview with Rolling Stone magazine because he was too busy. I see our interview referenced in many books about Jerry because I think we were among the few interviewers to ask him questions outside of music, like about his near-death experience, God, psychic phenomena, and synchronicity. Here are some excerpts from our conversation:

David: Joseph Campbell, the renowned mythologist, attended a number of your shows. What was his take?

Jerry: He loved it. For him, it was the bliss he’d been looking for. “This is the antidote to the atom bomb,” he said at one time.

David: He also described it as a modern-day shamanic ritual, and I’m wondering what your thoughts are about the association between music, consciousness, and shamanism.

Jerry: If you can call drumming music, music has always been a part of it. It’s one of the things that music can do— it can transport. That’s what music should do at its best— it should be a transforming experience. The finest, the highest, the best music has that quality of transporting you to other levels of consciousness.

David: I’m curious about how psychedelics influenced not only your music but your whole philosophy of life.

Jerry: Psychedelics were probably the single most significant experience in my life. Otherwise, I think I would be going along believing that this visible reality here is all that there is. Psychedelics didn’t give me any answers. What I have are a lot of questions. One thing I’m certain of; the mind is incredible and there are levels of organizations of consciousness that are way beyond what people are fooling with in day-to-day reality.

David: How did psychedelics influence your music before and after?

Jerry: Phew! I can’t answer that. There was a me before psychedelics and a me after psychedelics, that’s the best I can say. I can’t say that it affected the music specifically, it affected the whole me. The problem of playing music is essentially of muscular development and that is something you have to put in the hours to achieve no matter what. There isn’t something that strikes you and suddenly you can play music.

David: You’re talking about learning the technique, but what about the inspiration behind the technique?

Jerry: I think that psychedelics was part of music for me in so far as I’m a person who was looking for something and psychedelics and music are both part of what I was looking for. They fit together, although one didn’t cause the other.

David: What’s your concept of God if you have one?

Jerry: I was raised a Catholic so it’s very hard for me to get out of that way of thinking. Fundamentally I’m a Christian in that I believe that to love your enemy is a good idea somehow. Also, I feel that I’m enclosed within a Christian framework so huge that I don’t believe it’s possible to escape it, it’s so much a part of the Western point of view. So I admit it, and I also believe that real Christianity is okay. I just don’t like the exclusivity clause. But as far as God goes, I think that there is a higher order of intelligence something along the lines of whatever it is that makes the DNA work. Whatever it is that keeps our bodies functioning and our cells changing, the organizing principle— whatever it is that created all these wonderful life forms that we’re surrounded by in its incredible detail.

There’s a huge vast wisdom of some kind at work here. Whether it’s personal— whether there’s a point of view in there, or whether we’re the point of view, I think is up for discussion. I don’t believe in a supernatural being…. I’ve been spoken to by a higher order of intelligence— I thought it was God. It was a very personal God in that it had the same sense of humor that I have. I interpret that as being the next level of consciousness, but maybe there’s a hierarchical set of consciousnesses. My experience is that there is one smarter than me, that can talk to me, and there’s also the biological one that I spoke about.