Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

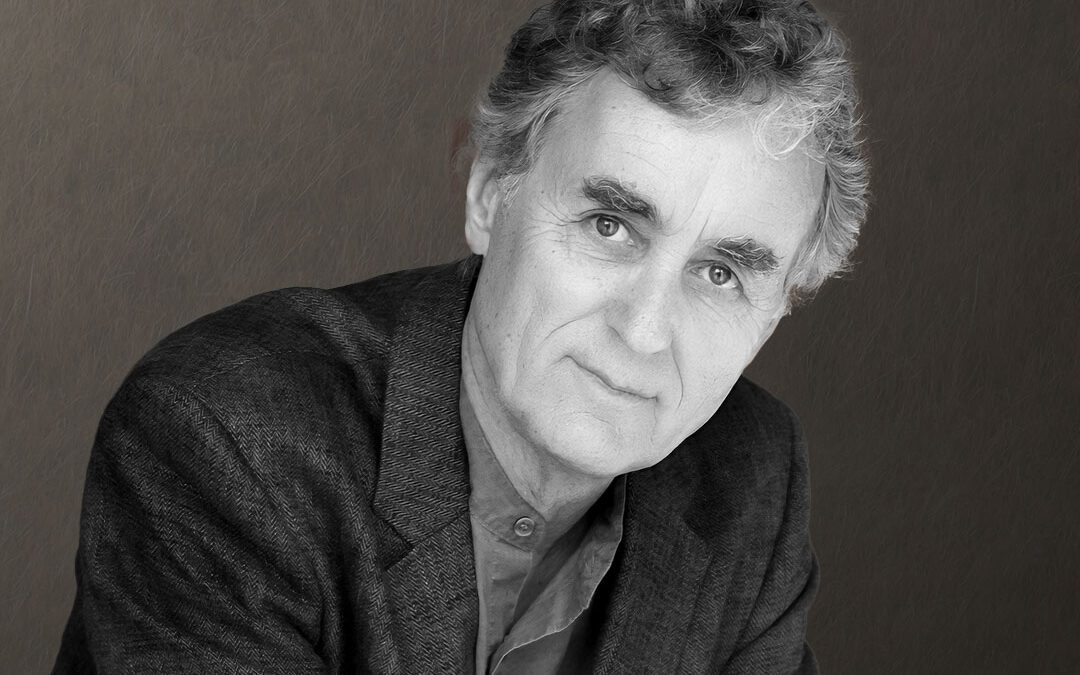

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of physicist, activist, and ecologist Fritjof Capra, who is the founding director of the Center for Ecoliteracy, and author of several bestselling books, including The Tao of Physics, which explores the relationship between Eastern philosophy and modern physics.

Fritjof Capra was born in Vienna, Austria in 1939. His father was an attorney and his mother was a poet. Capra attended the University of Vienna and earned his Ph.D. in theoretical physics in 1966. Capra also studied numerous languages and is fluent in German, English, Italian, and French.

Capra conducted physics research at several prestigious institutions. Between 1966 and 1968, he was a researcher at the University of Paris. Between 1968 and 1970, he conducted research at the University of California, Santa Cruz. In 1970, he was a researcher at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center in Palo Alto, California, and then at Imperial College in London between 1971 and 1974. Between 1975 and 1988, Capra worked at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory in Northern California.

Capra was involved in theoretical high-energy physics research, focusing on quantum field theory and particle physics. He worked on topics related to the physics of subatomic particles, exploring the fundamental forces and interactions that govern their behavior. Capra’s work included studying the properties and interactions of elementary particles, contributing to the understanding of quantum mechanics, and developing theoretical frameworks that describe particle interactions.

In 1975, while Capra was a researcher in Northern California, he joined the Fundamental Fysiks Group, which met weekly to discuss philosophy and quantum physics. Our friend Nick Herbert, who I wrote a profile about a while back, was also a member of this legendary group that revolutionized physics. David Kaiser’s book How the Hippies Saved Physics, chronicles how this group of unconventional physicists in the 1970s, blended psychedelic and counterculture influences with scientific inquiry, to help revive interest in the foundations of quantum mechanics and contribute to the development of quantum information science.

That same year Capra published his groundbreaking book The Tao of Physics, which became a bestseller and was translated into twenty-three languages. The book explores the parallels between modern physics and Eastern mysticism, suggesting that both realms offer complementary perspectives on the nature of reality. Capra argues that quantum mechanics and relativity discoveries reflect the holistic and interconnected worldview found in ancient spiritual traditions such as Taoism, Buddhism, and Hinduism.

In 1982, Capra published his book The Turning Point, which examines the failures of modern society’s mechanistic worldview and advocates for a paradigm shift towards a more holistic, ecological approach to science, economics, and society. In 1988, Capra published Uncommon Wisdom: Conversations with Remarkable People, a series of dialogues that he had with several brilliant thinkers, such as Alan Watts, Gregory Bateson, Krishnamurti, and R.D. Laing about the interconnectedness of life and the universe.

In 1990, the movie Mindwalk — starring Liv Ullmann, Sam Waterston, and John Heard— was released, and Capra co-wrote the screenplay. The film — which is about three people who engage in a deep philosophical discussion on a variety of topics, including science, politics, and the interconnectedness of life, while walking around the island of Mont Saint-Michel in France — is loosely based on his book, The Turning Point.

In 1991 Capra co-authored Belonging to the Universe: Explorations on the Frontiers of Science and Spirituality with a Benedictine monk David Steindl-Rast. The book explores parallels between new paradigm thinking in science and religion, and it won the American Book Award in 1992.

In 1995, Capra co-founded the Center for Ecoliteracy in Berkeley, California. The organization is dedicated to promoting ecological education in schools and integrates ecological principles into the curriculum to foster environmental awareness and sustainability among students. It has supported projects in habitat restoration, school gardens, and cooking classes, partnerships between farms and schools, school food transformation, and curricular innovation.

In 1996, Capra published his book The Web of Life, which presents a new scientific understanding of living systems, emphasizing the interconnectedness and interdependence of all life forms through the principles of complexity, networks, and ecology. In 1998, Capra received the New Dimensions Broadcaster Award, in 1999 he received the Bioneers Award, and in 2007 he was inducted into the Leonardo da Vinci Society for the Study of Thinking.

In 2002, Capra published The Hidden Connections, and he co-authored The Systems View of Life in 2014. Both books emphasize the interconnectedness and complexity of living systems, integrating perspectives from biology, ecology, and social sciences to understand the holistic nature of life. Capra has also taught physics classes at the University of California Santa Cruz, University of California, Berkeley, and San Francisco State University over the years.

In 2018, at an event hosted by our friend Ralph Abraham, I met Fritjof Capra. I told him how much I had enjoyed his book The Tao of Physics, and asked him about his inspiration for writing it. Fritjof then described to me how he was sitting on a beach in Santa Cruz when he experienced the revelations that led to his integration of physics with Taoism, and how mystical experiences that he had with “power plants” had played a role in his insight.

Some of the quotes that Fritjof Capra is known for include:

The mystic and the physicist arrive at the same conclusion; one starting from the inner realm, the other from the outer world. The harmony between their views confirms the ancient Indian wisdom that Brahman, the ultimate reality without, is identical to Atman, the reality within.

Mystics understand the roots of the Tao but not its branches; scientists understand its branches but not its roots. Science does not need mysticism and mysticism does not need science; but man needs both.

Quantum theory thus reveals a basic oneness of the universe. It shows that we cannot decompose the world into independently existing smallest units. As we penetrate into matter, nature does not show us any isolated “building blocks,” but rather appears as a complicated web of relations between the various parts of the whole. These relations always include the observer in an essential way. The human observer constitute the final link in the chain of observational processes, and the properties of any atomic object can be understood only in terms of the object’s interaction with the observer.

The more we study the major problems of our time, the more we come to realize that they cannot be understood in isolation. They are systemic problems, which means that they are interconnected and interdependent.

At the deepest level of ecological awareness you are talking about spiritual awareness. Spiritual awareness is an understanding of being imbedded in a larger whole, a cosmic whole, of belonging to the universe.

In ordinary life, we are not aware of the unity of all things, but divide the world into separate objects and events. This division is useful and necessary to cope with our everyday environment, but it is not a fundamental feature of reality. It is an abstraction devised by our discriminating and categorizing intellect. To believe that our abstract concepts of separate ‘things’ and ‘events’ are realities of nature is an illusion.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of pioneering cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead, who profoundly influenced the social sciences by studying the behavioral patterns of different cultures, particularly in the South Pacific. Mead’s groundbreaking work challenged Western perceptions of human development and sexuality, emphasizing cultural variability.

Margaret Mead was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1901. Her father was a professor of finance, her mother was a sociologist, and she had four younger siblings. As a child, Mead’s family moved around frequently, and her grandmother largely educated her.

In 1912, when Mead was eleven, she was enrolled at the Buckingham Friends School in Lahaska, Pennsylvania. In 1919, Mead studied for a year at DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana, and then she transferred to Barnard College in New York City. Mead graduated from Barnard in 1923, and then she received her master’s degree in psychology from Columbia University a year later.

In 1925, Mead set out for the Polynesian island of Tau in the South Pacific Ocean. This was where she did her first ethnographic fieldwork, studying the life of Samoan girls and women. Mead’s observations were summarized in the now-classic book Coming of Age in Samoa, published in 1928, and describe how Samoan children were raised and educated and how sexual relations occurred in the culture. Mead also studied personality development on the island, as well as dance, interpersonal conflict, and how Samoan women matured into old age.

Coming of Age in Samoa contrasts development in Samoa with that in the United States, and the book was received with wide acclaim for its revolutionary approach to understanding adolescence in different cultures. It became a bestselling work and has been highly influential in the field of anthropology. However, it wasn’t without controversy. Some conservative groups and individuals were uneasy with the book’s conclusions, which contradicted traditional views on adolescence and morality.

In 1926, Mead was back in New York City, where she became an assistant curator at the American Museum of Natural History, and in 1929 she received her Ph.D. in anthropology from Columbia University.

In 1929, Mead visited the island of Manus, which is now part of Papua New Guinea, where she did more cultural studies. In 1930, Mead published her book Growing Up in New Guinea, which is about her encounters with the indigenous people of the Manus— before they had been changed by missionaries and other Western influences— and she compares their views on family, marriage, sex, child-rearing, and religious beliefs to those of westerners. As with her pioneering studies in Samoa, Mead’s studies in New Guinea also challenged prevailing Western views on adolescence, gender roles, and cultural norms.

In 1932, Mead met anthropologist Gregory Bateson while conducting anthropological fieldwork on the shores of the Sepik River in New Guinea, and they married in 1936. That same year, the couple traveled to Bali, Indonesia, where they helped to pioneer Visual Anthropology, a subfield of anthropology that uses visual media— such as film, photography, and digital imagery— to study and communicate cultural practices and social phenomena. Mead and Bateson were some of the earliest anthropologists to emphasize the importance of photography as a tool for ethnographic research, and they used visual media extensively during their fieldwork to capture cultural practices and everyday life. They believed that visual records provided invaluable data and insights that complemented written ethnographies.

In 1935, Mead published Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies. This is a study of the intimate lives of three New Guinea tribes from infancy to adulthood. Focusing on the “gentle, mountain-dwelling Arapesh, the fierce, cannibalistic Mundugumor, and the graceful headhunters of Tchambuli,” Mead advanced the theory that many so-called masculine and feminine characteristics are not based on biological sex differences but reflect the cultural conditioning of different societies. For example, the Tchambuli tribe exhibited a unique gender role reversal, compared to the West, in which women dominated economic and social activities while men engaged in artistic and emotionally expressive pursuits.

Mead continued to study the cultures of the Pacific islands. In 1949, she published Male and Female, an anthropological examination of seven Pacific island tribes. Mead analyzed the dynamics of these cultures, to explore the evolving meaning of “male” and “female” in contemporary American society, and the book also offers hope, by providing examples of how to resolve conflict between the sexes. When it was published The New York Times declared, Dr. Mead’s book has come to grips with the cold war between the sexes and has shown the basis of a lasting sexual peace.”

From 1946 to 1969, Mead was curator of ethnology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, where she had been an assistant curator twenty years earlier. From 1954 to 1978, Mead taught anthropology at Columbia University and The New School for Social Research in New York City. In 1960, Mead served as president of the American Anthropological Association in the 1960s and 1970s, and she held various positions in the New York Academy of Sciences and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Mead also had an interest in altered states of consciousness. She shared professional circles with, and interacted with, our friends neuroscientist John C. Lilly and psychologist Timothy Leary. Mead and Bateson contributed to conversations about the nature of human consciousness by emphasizing cultural relativity, interconnectedness, and systems thinking. In later life, Mead mentored many young anthropologists and sociologists, including psychologist Jean Houston, whom I did a profile about several months ago. In 1976, Mead was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. Mead died in 1978 at the age of 76.

In 1979, U.S. President Jimmy Carter announced he was awarding the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously to Mead. In 1984, Mead and Bateson’s daughter, anthropologist Mary Catherine Bateson, published a book, With a Daughter’s Eye, about her experience growing up with two of the world’s legendary anthropologists. In 1998, the U.S. Post Office issued a 32-cent stamp with Mead’s face.

The Margaret Mead Award is presented annually in Mead’s honor by the Society for Applied Anthropology and the American Anthropological Association, for significant works that communicate anthropology to the general public. There are schools named after Mead: a junior high school in Elk Grove Village, Illinois, an elementary school in Sammamish, Washington, and another in Brooklyn, New York.

Some of the quotes that Margaret Mead is known for include:

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed, citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.

Children must be taught how to think, not what to think.

I was wise enough never to grow up, while fooling people into believing I had.

Laughter is man’s most distinctive emotional expression.

As the traveler who has once been from home is wiser than he who has never left his own doorstep, so a knowledge of one other culture should sharpen our ability to scrutinize more steadily, to appreciate more lovingly, our own.

Always remember that you are absolutely unique. Just like everyone else.

… the ways to get insights are: to study infants; to study animals; to study primitive people; to be psychoanalyzed; to have a religious conversion and get over it; to have a psychotic episode and get over it; or to have a love affair with an old Russian…

An ideal culture is one that makes a place for every human gift.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of Danish physicist and philosopher Niels Bohr, who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922. He was also one of the first to consider and explore “quantum metaphysics,” the notion that matter is derived from consciousness.

Niels Henrik David Bohr was born in Copenhagen, Denmark in 1885. He was the second of three children. His father was a professor of physiology, and his mother came from a wealthy Jewish banking family.

When he was seven, Bohr started his education at Gammelholm Latin School. In 1903, he enrolled at Copenhagen University, where he studied physics, astronomy, mathematics, and philosophy. In 1905, Bohr won a gold medal competition for a physics contest measuring the surface tension of liquids, that he had to make his specialized glassware for. He later submitted an improved version of this paper, which was published by the Royal Society of London.

In 1909, Bohr received his master’s degree in mathematics, and in 1911 he received his doctorate in physics from Copenhagen University for his research into the magnetic properties of metals. During this time Bohr also met and married Margrethe Norlund, a Danish woman who collaborated with him on his research and helped to edit and transcribe his work.

In 1911, Bohr traveled to England, where most of the theoretical work on the structure of atoms and molecules was being done. He studied electromagnetism and researched cathode rays. In 1912, he began teaching physics to medical students at the University of Copenhagen, and in 1913 he did revolutionary work on creating a new model of the atom that became known as the “Bohr model” of the atom, which is the most basic particle of the chemical elements. This model of the atom consists of a small, dense nucleus surrounded by orbiting subatomic particles called “electrons,” in a way that is analogous to the structure of the solar system.

Bohr advanced atomic theory by proposing that electrons travel in orbits around the nucleus, or center of the atom, in “stationary states” that stabilize the atom. Bohr also introduced the idea that an electron could drop from a higher-energy orbit to a lower one, and in this process emit a “quantum” of discrete energy.

A quantum is the minimum amount of energy in any physical interaction between the fundamental forces of nature. Bohr’s theory became a basis for what is now known as the “old quantum theory”—which predates modern quantum mechanics. This was considered a breakthrough by many physicists of his day, including Albert Einstein.

In 1916, Bohr was appointed as the Chair of Theoretical Physics at the University of Copenhagen, a position that was created especially for him. In 1918, he established an Institute of Theoretical Physics at the university, where he became the director, and this institute is today known as the Niels Bohr Institute. Bohr was extremely dedicated to this work, and he and his family moved into an apartment on the first floor. Bohr’s institute served as a focal point for researchers into quantum mechanics during the 1920s and 1930s, when most of the world’s best-known theoretical physicists spent time there.

In 1919, Bohr revised his model of the atom, and its relationship with electrons, and in 1921, he published a paper that showed that the chemical properties of each element were largely determined by the number of electrons in the outer orbits of its atoms. In 1922, Bohr was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics “for his services in the investigation of the structure of atoms and the radiation emanating from them.”

In 1924, physicist Werner Heisenberg — who developed the mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics, and a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics known as the “uncertainty principle”— came to the University of Copenhagen, where he worked as an assistant to Bohr from 1926 to 1927, and they had an important influence on one another. Around this time, Bohr became convinced that light behaved like both waves and particles, and he conceived the philosophical principle of “complementarity,” which proposed that physical structures could have, what appear to be, mutually exclusive properties — such as being a wave or a stream of particles, depending on the experimental framework, or one’s perspective.

Heisenberg said that Bohr was “primarily a philosopher, not a physicist.” Bohr was influenced by Soren Kierkegaard’s philosophy, and he had an interest in metaphysics and psychic phenomena. In 1932, Bohr met with psychiatrist Carl Jung at a conference on intellectual cooperation, and they discussed the concept of synchronicity— the simultaneous occurrence of events that appear significantly related but have no discernible causal connection. Bohr was also interested in the concept of psychokinesis — the influencing of matter by thought — and he believed that parapsychology was worthy of study. Bohr was also one of the first to consider and explore the concept of “quantum metaphysics,” the notion that matter is derived from consciousness.

In 1940, early in the Second World War, Nazi Germany invaded and occupied Denmark. In 1943, word reached Bohr that the Nazis considered him to be Jewish since his mother was Jewish and that he was therefore in danger of being arrested. The Danish resistance helped Bohr and his wife escape to Sweden.

In 1943, Bohr arrived in Washington, D.C., where he met with the director of the Manhattan Project, the research program that led to the development of the atomic bomb. Bohr visited Einstein at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, and went to Los Alamos in New Mexico, where the atomic bomb was being designed.

Bohr did not remain at Los Alamos, but he paid a series of extended visits there over the next two years. Physicist Robert Oppenheimer credited Bohr with acting “as a scientific father figure to the younger men” that were there, and Oppenheimer gave Bohr credit for an important contribution to the work on an essential part of the project called “modulated neutron initiators.” “This device remained a stubborn puzzle,” Oppenheimer said, “but in early February 1945 Niels Bohr clarified what had to be done.”

Following the end of the war in 1945, Bohr returned to Copenhagen, where he was elected as president of the Royal Danish Academy of Science. In 1947, the king of Denmark, Frederik IX, awarded Bohr with membership in the Order of the Elephant — a Danish order of chivalry and is Denmark’s highest-ranked honor — which was normally only awarded to royalty and heads of state. Bohr designed his coat of arms, which included a Chinese yin-yang symbol in its center, signifying that “opposites are complementary.” Bohr also received numerous other awards and honors, such as the Matteucci Medal, the Copley Medal, and the Atoms for Peace Award.

In 1962, Bohr died of heart failure at his home in Carlsberg, Denmark.

In 1963, the Bohr model’s semi-centennial was commemorated in Denmark with a postage stamp depicting Bohr, the hydrogen atom, and the formula for the difference in hydrogen energy levels. Several other countries have also issued postage stamps depicting Bohr. In 1997, the Danish National Bank began circulating the 500-krone banknote with a portrait of Bohr smoking a pipe. Additionally, an asteroid, 3948 Bohr, was named after him, as was the Bohr Lunar Crater, and Bohrium, the chemical element with atomic number 107.

Some of the quotes that Niels Bohr is known for include:

Everything we call real is made of things that cannot be regarded as real. If quantum mechanics hasn’t profoundly shocked you, you haven’t understood it yet.

An expert is a person who has made all the mistakes that can be made in a very narrow field.

The opposite of a correct statement is a false statement. But the opposite of a profound truth may well be another profound truth.

No, no, you’re not thinking; you’re just being logical.

There are some things so serious that you have to laugh at them.

A physicist is just an atom’s way of looking at itself.

The meaning of life consists in the fact that it makes no sense to say that life has no meaning.

We must be clear that when it comes to atoms, language can be used only as in poetry. The poet, too, is not nearly so concerned with describing facts as with creating images and establishing mental connections.

Every sentence I utter must be understood not as an affirmation, but as a question.

Your theory is crazy, but it’s not crazy enough to be true.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, whose painting The Scream has become one of Western art’s most iconic images. Munch is also known for his “soul paintings,” and he was knighted by Norwegian royalty.

Edvard Munch was born in Adalsbruk, Norway in 1863. His father was a doctor and medical officer, who Munch described as “obsessively religious.” His mother was artistically talented, and she encouraged her son to express himself creatively. Munch had an older sister and three younger siblings.

In 1864, Munch’s family moved to Oslo. In 1868, his mother, as well as his older sister, died of tuberculosis, which had a profound impact on him. After his mother’s death, his aunt helped to raise the family. Munch was often ill as a child and kept out of school. During this time, he would often spend his time drawing and painting in watercolors. Munch was tutored in history and literature by his father, who often entertained the family with stories by the American writer Edgar Allan Poe.

The combination of an oppressive religious environment, his poor health, and vivid mystery stories by Poe, worked together to instill nightmares and macabre visions in young Munch’s mind. One of his younger sisters was diagnosed with mental illness at an early age and committed to a mental asylum. There was so much darkness in Munch’s early life that he often expressed the fear that he was going insane.

Munch’s earliest drawings and watercolors depicted the interior of his home and medicine bottles, but he soon began painting some landscapes. By the time Munch was a teenager, art became his primary interest. In 1876, Munch had his first exposure to other artists at the Norwegian Landscape School, where he began to paint in oils and tried to copy the paintings that he was exposed to.

In 1879, Munch enrolled in a technical college, where he studied engineering and excelled in physics, chemistry, and mathematics. He also learned scaled and perspective drawing techniques. Although he did well in college, he left school after just a year, with the determination to become a painter. Munch’s father was disappointed in his son’s decision, as he viewed art as an “unholy trade.” However, Munch saw his art as his salvation, and wrote the following in his diary around this time: “In my art, I attempt to explain life and its meaning to myself.”

In 1881, Munch enrolled at the Royal School of Art and Design in Oslo, which was founded by a distant relative. In 1883, Munch took part in his first public exhibition, and he became friendly with other art students. Munch was inspired by the art movement of Impressionism, which is characterized by small but visible brushstrokes that emphasize the depiction of light in its changing qualities. He was also influenced by Naturalism, which, in contrast, attempts to represent subject matter realistically, and he later became associated with the Symbolist Movement, which sought to depict ideas and emotions hidden behind physical reality.

Munch’s early work consisted largely of self-portraits and nudes. Sadly, all but one of his nude paintings from this period survive, as the others were destroyed by his father, who then refused to give his son any further money for art supplies. In 1886, Munch concluded that Impressionism was too superficial, and he broke off into new experimentation with what he called “soul painting.” This approach to his art served as a means of exploring and expressing the innermost feelings, thoughts, and experiences of the human psyche.

Munch believed that art should transcend the visual representation of the external world and delve into the subjective experience of the individual. “Soul painting” was not just a technique but a philosophy for Munch. It was about revealing the internal struggles and deeper realities of human existence, “making visible what was invisible to the eye.” Through “soul painting,” Munch aimed to capture the anguish, loneliness, love, and despair that he felt and perceived in others. His “soul paintings” were characterized by their evocative use of color, dramatic compositions, and often unsettling subjects that reflect complex emotional states.

His first painting of this type was The Sick Child, which was based on his sister’s death. This painting evolved into six paintings with that title, which record the moment before the passing of his older sister. These six paintings were created over more than forty years, between 1885 through 1926. They all depict variant images of the same scene; his sister lying ill in bed with his aunt kneeling beside her.

In 1889, Munch moved to Paris, and one of his paintings was shown at the Paris Exposition that year. He spent his time at exhibitions, galleries, and museums. Later that year his father died, and Munch returned to Oslo. While he was there, he arranged for a large loan from a wealthy Norwegian art collector and assumed financial responsibility for his family from then on. Munch’s paintings during this time were largely of tavern scenes and bright cityscapes, and he experimented with different painting styles. Around this time, his work was shown at exhibitions in Oslo and also in Berlin. In 1892, he moved to Berlin, where he became involved with an international circle of writers and artists, and he stayed there for four years.

In 1893, Munch created the first version of his most well-known painting The Scream. This is Munch’s most famous work and one of the most recognizable paintings in all art history. It has been widely interpreted as representing the universal anxiety of modern man. Painted with broad bands of garish color and simplified forms, it reduces the agonized figure to a garbed skull in the throes of an emotional crisis.

There are several versions of this famous painting: two pastels, two oil paintings, and a lithograph. Pastel versions and the lithograph version were created in 1895. The second oil painting was completed in 1910. The original inspiration for this painting occurred while Munch had been out for a walk at sunset when suddenly the setting sun’s light turned the clouds “a blood red,” and he sensed an “infinite scream passing through nature.”

In 1908, Munch’s anxiety, which was compounded by excessive drinking, became more acute, and he began to suffer from hallucinations and feelings of persecution. This led to an eight-month hospital stay, where he underwent psychotherapy that stabilized his mind, and when he returned home his artwork was transformed. It became more colorful and less pessimistic. There was also more interest in his work after this dark night of the soul, and museums began to purchase his paintings. He was made a Knight of the Royal St. Olav — a Norwegian Order of Chivalry— “for services in art.” In 1912, he had his first American exhibit in New York.

Munch stopped drinking, and he produced portraits of friends and patrons. He also created landscapes and scenes of people at work and play, using a new optimistic style— broad, loose brushstrokes of vibrant color with frequent use of white space. With more income Munch was able to purchase several properties, giving him new vistas for his art, and he was finally able to provide for his family.

Munch spent the last two decades of his life largely in solitude at his estate in Oslo. Many of his late paintings celebrate farm life, including several in which his horse served as a model. Munch died in 1944, at the age of 80. After Munch died, many of his works were bequeathed to the city of Oslo, which built the Munch Museum. The museum houses the largest collection of his work in the world and holds around 1,100 paintings, 4,500 drawings, and 18,000 prints.

In 1974, a biographical film was made about Munch’s life called Edvard Munch. In 1994, the 1893 version of The Scream was stolen from the National Gallery in Oslo but was later recovered. Then in 2004, the 1910 version of the painting was stolen from the Munch Museum in Oslo, and it was recovered in 2006 with some damage. In 2012, the 1895 pastel version of The Scream sold for $119,922,500, and that is the only version of the painting not held by a Norwegian museum.

Some of the quotes that Edvard Munch is known for include:

From my rotting body, flowers shall grow, and I am in them, and that is eternity.

Nature is not only all that is visible to the eye… it also includes the inner pictures of the soul.

I was walking along a path with two friends – the sun was setting – suddenly the sky turned blood red – I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence – there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city – my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.

The camera will never compete with the brush and palette until such time as photography can be taken to Heaven or Hell.

My fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness. Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder. My art is grounded in reflections over being different from others. My sufferings are part of myself and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art. I want to keep those sufferings.

I felt as if there were invisible threads connecting us— I felt the invisible strands of her hair still winding around me— and thus as she disappeared completely beyond the sea— I still felt it, felt the pain where my heart was bleeding— because the threads could not be severed.

Your face encompasses the beauty of the whole earth. Your lips, as red as ripening fruit, gently part as if in pain. It is the smile of a corpse. Now the hand of death touches life. The chain is forged that links the thousand families that are dead to the thousand generations to come.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of novelist, poet, and playwright Oscar Wilde, who was one of the most popular playwrights in London during the early 1890s and became the target of a criminal prosecution involving his homosexuality. Wilde is most well-known for his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray and for his plays Lady Windermere’s Fan and The Importance of Being Ernest.

Oscar Wilde was born in Dublin, Ireland in 1854. He was the second of three children. Wilde‘s mother was a poet and a supporter of the Irish nationalist movement. His father was Ireland’s leading ear and eye surgeon. He was also a renowned philanthropist, who was knighted for his service as a health adviser for the nation and also wrote books about Irish archeology and peasant folklore.

Wilde was educated at home, until the age of nine, by a French nursemaid and German governess who taught him their languages. In 1864, Wilde entered the Portora Royal School in Northern Ireland, where he studied for seven years, and was regarded as a prodigy for his ability to speed read. Wilde was able to read two pages simultaneously and could consume a three-volume book in 30 minutes.

In 1871, Wilde won a scholarship to attend Trinity College in Dublin, where he studied literature and the classics for three years. During this time Wilde established himself as an outstanding student. He was first in his class in his freshman year, and he began publishing poems in magazines.

During Wilde’s second year, he was elected as one of the Scholars of Trinity College, which was described as “the most prestigious undergraduate award in the country.” In his final year, he won the university’s highest academic award, the Berkely Gold Medal in Greek. Wilde was then awarded a scholarship to Magdalen College in Oxford, where he continued his studies from 1874 to 1878.

At Magdalen College Wilde wore his hair long, and became a Freemason. He also developed an interest in Catholicism, and he became widely known for his role in the Decadent Movement. The Decadent Movement was an artistic and literary trend that was characterized by a belief in the superiority of fantasy and aesthetic hedonism over logic and the natural world.

In 1878, Wilde won the Newdigate Prize from the University of Oxford for his poem Ravenna, which was about his time in Oxford. That same year he graduated with a degree in the classics from Magdalen College and returned to Dublin, where he regularly attended theater performances.

In 1880, Wilde completed his first play, Vera; or The Nihilists, which is a tragedy set in Russia, and loosely based on the life of writer and social activist Vera Zasulich. A year later arrangements were made for it to be performed in London, but the production was canceled, due to political reasons. The first performance was in 1883 in New York, although it wasn’t a success and folded after just a week.

In 1881, Wilde published a collection of his poetry titled Poems, which sold out the first print run of 750 copies, although it wasn’t generally well received by critics, and the Oxford Union condemned the book for alleged plagiarism. Nonetheless, it had further printings, and Wilde presented many copies of the book to the dignitaries and writers who received him during his later lecture tours.

In 1883, Wilde visited Paris, where he wrote a five-act tragedy titled The Duchess of Padua, which was turned down by the actress it was written for and abandoned until 1891 when it was performed on Broadway in New York, but only ran for three weeks.

In 1890, Wilde published his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, a philosophical story about someone who sells his soul in exchange for lasting youth, so that a portrait of him ages and fades rather than his physical appearance. The book was controversial when it was first published. Many critics felt that it was not only poorly written but “vulgar” and had a “superficial view of beauty,” although today it is largely considered to be a seminal work in literature and a timeless classic.

In 1891, Wilde finished his drama Salome but was met with a refusal for it to be performed in England at the time, due to a prohibition on the portrayal of Biblical subjects on the English stage. However, Wilde produced a sequence of four society comedies in the early 1890s, which made him one of the most successful playwrights in London and defined his legacy.

In 1892, Wilde completed a social satire titled Lady Windermere’s Fan, which is about a woman who suspects that her husband is having an affair, and it ran for 197 performances that year. In 1893, this was followed by A Woman of No Importance, which satirizes English upper-class society and ran for 113 performances. In 1895, An Ideal Husband was released, which revolves around blackmail and political corruption, and it ran for 124 performances.

That same year, The Importance of Being Ernest was released, which became one of his most celebrated works. This play was an exaggerated comedy about someone who maintains a fictitious persona to escape burdensome social obligations. The successful opening night marked the climax of Wilde’s career, the height of his fame and success, but also heralded his downfall. The Marquees of Queensberry, whose gay son Lord Alfred Douglas was Wilde’s lover, planned to present the writer with a bouquet of rotten vegetables to disrupt the show. However, Wilde was tipped off about his plans, and Queensberry was refused admission to the theater.

This angered Queensberry, who publicly accused Wilde of illegal homosexual acts. This allegation got Queensberry arrested for criminal libel, a charge with a possible sentence of two years in prison. However, Queensberry was able to avoid conviction for this if he could demonstrate that his accusation was true, so he hired private detectives to find evidence of Wilde’s gay liaisons.

Wilde’s friends warned him that this was a serious situation and that he should flee to France, but he didn’t heed their advice. When the case went to trial, Wilde’s private life, and his associations with male prostitutes in brothels, became public knowledge and began to appear in the press. Queensberry was acquitted after the trial, and Wilde had incurred considerable expenses in his defense, which left him bankrupt.

However, the worst was yet to come. After Wilde left the court, a warrant for his arrest was issued for the charges of “sodomy” and “gross indecency,” and soon thereafter he was arrested. Wilde was sentenced to two years imprisonment with hard labor, and his notoriety caused his play The Importance of Being Ernest to be closed after 86 performances.

In 1897, Wilde was released from prison, bankrupt and embittered. He moved to France and never returned to the United Kingdom again. The following year Wilde wrote his poem, The Ballad of Reading Gaol, which was his last published work, and is an eloquent plea for the reform of prison conditions.

Wilde died in 1900 in Paris, at the age of 46, of acute meningitis brought on by an ear infection. In his semiconscious final moments, Wilde was received into the Roman Catholic Church, which he had admired since his time in college. He is buried in the Pere Lachaise Cemetery, the largest cemetery in Paris. Wilde wrote a total of nine plays and 43 poems during his lifetime.

In 1995, Wilde was commemorated with a stained-glass window at Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey, London. In 2014, Wilde was one of the inaugural honorees in the Rainbow Honor Walk, a walk of fame in San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood noting LGBTQ people who have “made significant contributions in their fields.” In 2017, Wilde was among around 50,000 men who were pardoned for homosexual acts that were no longer considered criminal offenses in England.

Some of the quotes that Oscar Wilde is known for include:

Be yourself; everyone else is already taken.

To live is the rarest thing in the world. Most people exist, that is all.

I am so clever that sometimes I don’t understand a single word of what I am saying.

We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.

Never love anyone who treats you like you’re ordinary.

Most people are other people. Their thoughts are someone else’s opinions, their lives a mimicry, their passions a quotation.

You don’t love someone for their looks, or their clothes, or for their fancy car, but because they sing a song only you can hear.

I never travel without my diary. One should always have something sensational to read in the train.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of Italian poet, writer, and philosopher Dante Alighieri, who is best known for his epic work The Divine Comedy, which is widely considered one of the most important poems of the Middle Ages, and the greatest literary work in the Italian language. Dante was instrumental in establishing the literature of Italy, and he is considered to be one of the Western world’s greatest literary icons.

Dante Alighieri was born in the Republic of Florence, in what is now Italy, around 1265, although the exact year of his birth isn’t known. Dante’s family descended from the ancient Romans. His mother died when he was nine years old, and his father remarried a woman who brought him a half-brother and half-sister.

It is believed that Dante was educated at home, or in a chapter school attached to a church or monastery in Florence. He studied Tuscan poetry, and he admired the compositions of the Bolognese poet Guido Guinizelli. Dante also studied the poetry of the French troubadours and Latin writers of antiquity.

At the age of nine, Dante met a girl one year younger than himself named Beatrice Portinari, whom he claimed to have fallen in love with “at first sight.” At the age of twelve, Dante was promised marriage to someone else, Gemma Donati, as was common during this era. Years after his marriage, he met Beatrice again and wrote several sonnets for her, but he never mentioned his wife in any of his poems. Dante fathered three children with Gemma.

Dante’s interactions with Beatrice were an example of what was referred to as “courtly love,” or the romantic relationship between two unmarried people during medieval times. In many of Dante’s poems, Beatrice is depicted as semi-divine, always watching over him, and providing spiritual instruction.

As a teenager, Dante dedicated himself to philosophical studies at religious schools, such as the Dominican School in Santa Maria Novella. At around the age of eighteen, Dante met four other Italian poets— Guido Cavalcanti, Lapo Gianni, Cino da Pistoia, and Brunetto Latini— and they influenced one another’s poetic styles.

In 1289, Dante fought in the Battle of Campaldino, a war between factions supporting the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor in the Italian city-states of what is today Central and Northern Italy.

In 1295, Dante became a pharmacist and a politician. Although he never intended to practice as a pharmacist, he did this to develop a political career, as a law required nobles aspiring to public office to be enrolled in an occupation that allowed him admission into this elite guild. As a politician, he held various offices over some years in a city filled with much political unrest.

In 1302, Dante was accused of corruption and financial wrongdoing and was condemned to exile for two years and ordered to pay a large fine. Dante refused to pay the fine, as he did not believe that he was guilty and his assets in Florence were seized, so he was condemned to permanent exile. If he returned to Florence, he could have been burned at the stake. In 2008, almost seven centuries after his death, the city council of Florence passed a motion rescinding Dante’s sentence.

In 1306, Dante became the guest of the captain-general Moroello Malaspina in a historical region of Italy that was known as Lunigiana. After a year, he moved to another historical region of Italy known as Sarzana. Some scholars think that he later moved to another region known as Luca, and there are speculative claims that he visited Paris between 1308 and 1310.

During Dante’s exile, his interest in philosophy and literature deepened, as he was no longer busy with the day-to-day business of Florentine politics, and at some point, he conceived of The Divine Comedy. Although the date that he began his epic poem is uncertain, he worked on it throughout his life, and completed it around 1321, shortly before his death.

The Divine Comedy is a narrative poem, that depicts an imaginative vision of the afterlife. It is divided into three parts: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso, which vividly describe Dante’s personally guided tour of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven by three wise guides— Virgil, Beatrice, and Saint Bernard— who represent human reason, divine revelation, and contemplative mysticism respectively. The poem represents the state of the soul after death, its journey toward God, and presents an image of divine justice meted out as due punishment or reward.

The poem is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature, and one of the greatest works in Western literature, although it was not always as well-regarded as it is today. Although recognized as a masterpiece in the centuries immediately following its publication, the work was largely ignored during the 1700s and early 1800s.

The Divine Comedy was rediscovered in the English-speaking world by artist and poet William Blake— who illustrated several passages of the epic poem in 1826— and the Romantic writers of the 19th century. Later authors such as T. S. Eliot, Samuel Beckett, Ezra Pound, C. S. Lewis, and James Joyce drew on it for inspiration. There have since been numerous references to Dante’s work in literature, music, and sculpture, and many visual artists have illustrated scenes from The Divine Comedy.

Dante’s final days were spent in Ravenna, in what is today Northern Italy, where he was invited to stay in the city by its prince in 1318. Dante died in 1321 at around the age of 56, after contracting malaria while returning from a diplomatic mission to the Republic of Venice. He was buried in Ravenna, at the Church of San Pier Maggiore, which is known today as the Basilica di San Francesco. In 1483, the Praetor of Venice erected a tomb for him.

Today Dante is described as the “father” of the Italian language, and in Italy, he is often referred to as il Sommo Poeta (the Supreme Poet). In recent years, there have been many references to The Divine Comedy in pop culture, such as in film, television, comics, and video games. Dante also had a huge influence on my own work; my first book, Brainchild, which Carolyn did the cover art for, was inspired by The Divine Comedy.

Some of the quotes that Dante Alighieri is known for include:

Nature is the art of God.

The path to paradise begins in hell.

Love, that moves the sun and the other stars.

Beauty awakens the soul to act.

Remember tonight… for it is the beginning of always

The darkest places in hell are reserved for those who maintain their neutrality in times of moral crisis.

There is no greater sorrow than to recall happiness in times of misery.

From a little spark may burst a mighty flame.

Heaven wheels above you, displaying to you her eternal glories, and still your eyes are on the ground.

The secret of getting things done is to act!

Follow your own star!