Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky was born in Moscow, Russia, in 1821. He had an older brother, his father was a doctor, and he was raised in his family’s home, which was on the grounds of the Mariinsky Hospital for the Poor. This hospital was in a lower-class district on the edges of Moscow, and when playing in the hospital gardens as a child Dostoevsky encountered patients who were at the bottom of the Russian social scale.

When Dostoyevsky was four years old his mother used the Bible to teach him how to read and write, and he was introduced to books at an early age. His nanny read him fairy tales, legends, and heroic sagas, and his parents introduced him to a wide range of literature. Although his father’s approach to education has been described as “strict and harsh,” Dostoevsky reported that his “imagination” was “brought alive” by his parent’s nightly readings.

In 1837 Dostoyevsky left school to enter the Nikolayev Military Engineering Institute, and after graduating he worked as a lieutenant engineer and book translator, from French into Russian. In 1839 signs of Dostoevsky’s epilepsy first appeared, and his seizures plagued him throughout his life. During his 20s, Dostoyevsky recorded several journal descriptions of his seizures, and there are also descriptions in his novels. There have been numerous medical hypotheses about the type of epilepsy with which Dostoevsky suffered, the most notorious feature of his type of epilepsy being the so-called “ecstatic aura.” While these seizures were debilitating, they also appear to have contributed to mystical experiences that enhanced the creativity of his writing.

Dostoyevsky had this to say about his epileptic seizures, “I felt that heaven descended to earth and swallowed me. I attained God and was imbued with him… all the joys life can give I would not take in exchange for it… for a few moments before the fit, I experience a feeling of happiness such [that] it is impossible to imagine in a normal state and which other people have no idea of. I feel entirely in harmony with myself and the world, and this feeling is so strong and so delightful that for a few seconds of such bliss, one would gladly give up ten years of one’s life if not one’s whole life.”

Between 1844 and 1845 Dostoyevsky wrote his first novel, Poor Folk. His motivation for writing this novel was said to be largely financial. Dostoyevsky was having financial difficulties, due to an extravagant lifestyle and a gambling addiction, so he decided to write a novel to try and raise funds. The novel is written in the form of letters between the two main characters, who are poor relatives, and it describes the lives of poor people, their relationship with rich people, and poverty in general. This novel became a commercial success, and it gained Dostoyevsky’s entry into Saint Petersburg’s literary circles.

In 1846 Dostoyevsky’s second novel, The Double: A Petersburg Poem, about a bureaucrat struggling to succeed, was published in a journal and it received negative reviews. Around this time Dostoyevsky also published several short stories in a magazine, which also received negative reviews, and this caused him stress and greater financial difficulty. After this his health declined, his seizures increased in frequency, and Dostoyevsky’s life took a dark turn.

In 1847 Dostoyevsky was arrested for belonging to a particular literary group called the Petrashevsky Circle, which discussed banned books that were critical of Tsarist Russia. Dostoyevsky was sentenced to death, but at the last moment, his sentence was commuted. He later described this experience, of what he believed to be the last moments of his life, in his novel The Idiot. Dostoyevsky spent the next four years doing hard labor in a Siberian prison camp, where he had frequent seizures, and then after surviving that, he had to do six more years of compulsory military service.

In the years that followed Dostoyevsky worked as a journalist, editing several magazines, and he traveled around Western Europe. For a time, he experienced such serious financial hardship that he had to beg for money. In 1866, when he owed large sums of money to creditors, his widely acclaimed novel Crime and Punishment was first published in a literary journal, in twelve monthly installments. It was a “literary sensation” of 1866 and is now one of the most widely read books of all time.

The novel is about the mental anguish and moral dilemmas of an impoverished young man who plans to kill an unscrupulous old woman, who stores money and valuable objects in her apartment. What’s so remarkable about this story is how Dostoyevsky portrays the psychological process of his self-tormented main character.

Between 1868 and 1869 Dostoyevsky’s novel The Idiot was first published serially in a journal. The title of the book is an ironic reference to the central character of the novel, a young, Christ-like, epileptic prince whose “goodness, open-hearted simplicity, and guilelessness lead many of the more worldly characters he encounters to mistakenly assume that he lacks intelligence and insight.”

In 1880 Dostoyevsky published his final novel, The Brothers Karamazov, a passionate and philosophical story about rival love affairs, that explores questions of God, free will, and morality. Dostoevsky’s body of work consists of thirteen novels, three novellas, seventeen short stories, 221 Diary articles, and numerous other works.

Dostoyevsky died in 1881. Since his death, he has become one of the most widely-read and highly-regarded Russian writers. Dostoyevsky’s books have been translated into more than 170 languages, they’ve served as the inspiration for numerous films, and his work has influenced many other writers.

In 1971, Dostoevsky’s former apartment in Saint Petersburg was opened as a museum, known as the F.M. Dostoevsky Memorial Museum. The apartment was Dostoevsky’s home during the composition of some of his most notable works, including The Double: A Petersburg Poem and The Brothers Karamazov. The museum library holds around 24,000 volumes and a small collection of manuscripts.

Some quotes that Fyodor Dostoyevsky is remembered for include:

To love someone means to see them as God intended them.

Beauty will save the world.

What is hell? I maintain that it is the suffering of being unable to love.

I say let the world go to hell, but I should always have my tea.

It takes something more than intelligence to act intelligently.

Above all, don’t lie to yourself. The man who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to a point that he cannot distinguish the truth within him, or around him, and so loses all respect for himself and for others. And having no respect he ceases to love.

Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart. The really great men must, I think, have great sadness on earth.

Don’t let us forget that the causes of human actions are usually immeasurably more complex and varied than our subsequent explanations of them.

The mystery of human existence lies not in just staying alive, but in finding something to live for.

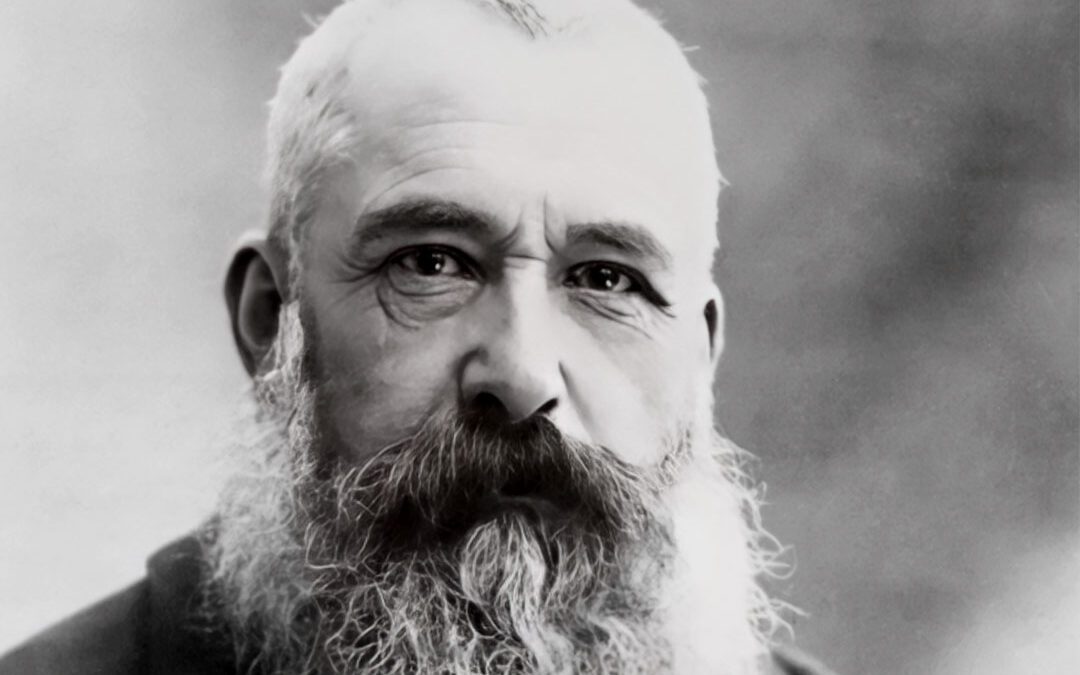

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of the French painter Claude Monet, who was a key figure in the Impressionist movement that transformed European painting in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Oscar-Claude Monet was born in 1840 in Paris. His father was a wholesale merchant, and his mother was a singer. In 1845 Monet’s family moved to Normandy, and his father wanted him to go into the family business of providing supplies to ships. However, Monet wanted to become an artist, and his mother supported his desire to be involved in the creative arts.

In 1851 Monet entered a secondary school of the arts. Although he had demonstrated skill in art from an early age, he was described as an “apathetic student.” At the age of 15 Monet began doing charcoal caricature drawings and portraits to earn money, and he started taking drawing lessons around this time as well. In 1858 Monet met another artist named Eugene Boudin, who taught him painting techniques and encouraged him with his art. At the time painting outside was relatively uncommon and Boudin taught Monet to paint outdoors and to pay attention to changing weather and light. Monet later said that Boudin was his “master,” and with regard to his later success that he “owed everything to him.”

From 1858 to 1860, Monet continued his studies at an academy in Paris, and then the following year he was called into the military service, where he served in Algeria from 1861 to 1862. The time that Monet spent in North Africa had a profound effect on him, and he said that the “light and vivid colors” there “contained the gem” of his future inspirations.

In 1862 Illness forced Monet to return to Paris, and it was during this time that he began his painting career. Monet often painted along the Seine River, alongside other painters, such as Renoir and Alfred Sisley. Monet and the other artists that he painted with sought to “articulate new standards of beauty in conventional subjects.”

It was during that time that Monet painted his first successful large-scale painting, known as Women in Garden, and in 1865 his paintings debuted at the Salon in Paris. This was the official annual art exhibition in France, where the best artists of the time would exhibit their work. After this exhibition, Monet submitted his paintings annually to the Salon until 1870, but they were only accepted by juries twice during this time, in 1866 and 1868.

In 1868, facing financial difficulties and severe depression, Monet jumped off a bridge into the Seine River, attempting to kill himself. Although he survived this suicide attempt, Monet struggled with depression for many years of his life.

For ten years Monet submitted no further paintings to the Salon, as his works were considered “radical,” and were “discouraged at all official levels.” During this time Monet’s father stopped financially supporting him because he disapproved of the woman that he was having a relationship with. Monet moved in with his aunt and immersed himself in his artwork, although he developed a problem with his eyesight that prevented him from working in the sunlight.

Monet painted numerous paintings of his family, and it was during this time that he began developing the style that was to become associated with his most well-known Impressionistic work. Impressionism is a style of painting characterized by small, visible brushstrokes that express a bare impression of form and unblended color, with an emphasis on the vivid depiction of natural light.

In 1874 Monet exhibited his paintings with an independent group called the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors and Engravers, whose title was chosen to avoid association with any particular style or movement. This was a group that Monet helped to form, and they were unified in their independence from the Salon and their rejection of the prevailing influence of the European academies of art. Monet had the reputation of being the foremost landscape painter of this group, which also included Renoir, Pissarro, and Cézanne.

Although the first exhibition with this new group received some unfavorable reviews, one art critic used the term “impressionism,” in a derogatory manner, to describe the artwork. This term was taken from Monet’s painting Impression, Sunrise, which conservative critics described as “unfinished.” More progressive critics praised the style as a “revolution in painting,” although Monet failed to sell this painting at the exhibit. Nonetheless, it was the title of this painting that served as the inspiration for the name of the artistic movement for which he is so well known.

In 1875, Monet returned to figure painting, and in 1880 he submitted two paintings to the Salon, one of which was accepted. Monet’s painting style began to shift around this time; he used less Impressionist techniques, utilized darker colors, and displayed natural environments, such as the Seine River, in harsh weather. For the rest of this decade, Monet focused on elemental aspects of nature, and he began to prosper financially with the success of his art, especially when his painting began to sell well in America.

Monet began to prefer working alone, and he thought that he did better work this way, after having “longed for solitude.” In 1883, Monet and his family rented a house and gardens in Giverny, which provided him with domestic stability. There was a barn on the property that doubled as a painting studio, as well as orchards and a small garden, and the surrounding landscape, provided many natural areas for Monet to paint.

In 1890 Monet purchased the house in Giverny, and his family worked to improve the property. They built up the gardens, as Monet had increasing success in selling his paintings. These gardens were Monet’s greatest source of inspiration for forty years. He imported plants from all over the world and diverted water from a nearby river to create a water garden. Monet wrote daily instructions to his gardener, precise designs and layouts for plantings, and as Monet’s wealth grew, his garden evolved.

Monet remained the architect of this magnificent garden, even after he hired seven gardeners, and he purchased additional land with a water meadow. The pond was enlarged in 1901 and 1910, with easels installed all around to allow different perspectives to be painted. At his house, Monet met with artists, writers, intellectuals, and politicians from around the world.

However, Monet’s neighbors weren’t exactly thrilled with his gardens; they were mostly cattle farmers who were afraid that his new aquatic plants would poison the water and kill their animals. Local authorities even told Monet to remove the plants, but he ignored them, and the water lilies became one of his greatest sources of inspiration. Over a period of thirty years, Monet created 250 paintings of water lilies.

During this time Monet began to develop cataracts, and his output decreased as he became withdrawn. This change in his vision affected his artwork, as the colors that he saw were no longer as bright, and his paintings began to feature more yellow and purple tones. However, he continued to paint, and he produced several panel paintings for the French Government from 1914 to 1918, and he completed work on a cycle of paintings between 1916 to 1921.

In 1923 Monet had surgery on his right eye, and the lens of his eye was removed, which let more light into the eye. Because the lens is part of the eye that filters out ultraviolet light, it is thought that Monet might have begun seeing ultraviolet wavelengths, which humans typically cannot see. After the surgery, Monet used more blues in his water lily paintings, which may indicate that he was seeing ultraviolet light.

Monet died in 1926 at the age of 86. He is buried at the Giverny church cemetery in France. Today Monet is recognized as the most well-known of the Impressionist painters, as a result of his numerous contributions to the movement, and the huge influence that he had on 19th-century art.

Monet was one of the most prolific French artists of all time, with over 2,500 oil paintings created to his name. Many of his paintings are in Parisian museums. The largest collection of Monet’s art can be seen at the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris, where 130 of his pieces are on display. The Musée d’Orsay and Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris also hold significant collections. In 1978, Monet’s garden in Giverny was restored and opened to the public, where it can be visited today.

Although Monet destroyed around 500 of his own paintings when he was angry or dissatisfied with his work, his paintings have sold for fortunes. In 2008 his painting Le Pont du Chemin de fer à Argenteuil, an 1873 painting of a railway bridge spanning the Seine River, was bought for $41.4 million, and Le Bassin Aux Nymphéas, from his water lilies series, sold for $80.4 million, which represented one of the top 20 highest prices paid for a painting at the time.

Some of the quotes that Claude Monet is known for include:

I must have flowers, always, and always.

Color is my daylong obsession, joy, and torment.

Every day I discover more and more beautiful things. It’s enough to drive one mad. I have such a desire to do everything, my head is bursting with it.

Everyone discusses my art and pretends to understand, as if it were necessary to understand, when it is simply necessary to love.

I would like to paint the way a bird sings.

My garden is my most beautiful masterpiece.

The richness I achieve comes from nature, the source of my inspiration.

I can only draw what I see.

When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have before you, a tree, a house, a field or whatever. Merely think here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact color and shape.

The light constantly changes, and that alters the atmosphere and beauty of things every minute.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of author Michael Murphy, who has been a key figure in the human potential movement and is co-founder of the Esalen Institute in Big Sur.

Michael Murphy was born in 1930 in Salinas, California. His father was Irish and his mother was Basque. In 1950 Murphy began studying at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, where he was enrolled in a pre-med program. One day Murphy accidentally wandered into a class on comparative religions, that was to change the course of his life. This accidentally attended lecture so inspired Murphy’s interest in Eastern and Western philosophy and spirituality that he enrolled in the class, and soon began practicing meditation.

In 1951, during a meditation experience by Lake Lagunita in Palo Alto, Murphy experienced a transformative vision that caused him to drop out of the pre-med program at Stanford with “a new purpose life.” Murphy switched his major to psychology, graduating from Stanford with a psychology degree in 1952.

After graduating from Stanford, Murphy spent two years in the U.S. Army, stationed in Puerto Rico as a psychologist. Then Murphy returned to Stanford, where he spent two quarters studying philosophy in graduate school, before embarking on a trip to India in 1956.

Between 1956 and 1957 Murphy practiced meditation at the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in Puducherry, India, where there was an established spiritual community. After this, he returned to California, and in 1960, while in residence at the Sri Aurobindo Ashram Fellowship in San Francisco, Murphy met Dick Price, who was also a Stanford University graduate, and they shared a common interest in psychology.

In 1962, Murphy and Price founded the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California on 127 acres of property that was owned by Murphy’s family. The grounds of the institute were originally home to a Native American tribe known as the Esselen, and carbon dating of artifacts found in this location has indicated a human presence there as early as 2600 BCE. The property was first homesteaded in 1882, and the hot springs there became a tourist attraction that was frequented by people seeking relief from physical ailments. In 1910 Murphy’s grandfather, a physician named Henry Murphy, purchased the property, and continued the hot springs business there.

The Esalen Institute became a retreat center that focuses on humanistic alternative education, and which many people consider to be the birthplace of the human potential movement. The organization has concentrated on teaching classes and workshops that explore personal growth, meditation, massage, ecology, yoga, psychology, the mind-body connection, and spirituality.

Some of the many incredible people who have taught at the Esalen Institute over the years include Abraham Maslow, Alan Watts, Timothy Leary, Fritz Perls, Nick Herbert, Robert Anton Wilson, Joseph Campbell, John Lilly, and Stanislav Grof. On average, more than 15,000 people a year from all over the world attend Esalen classes and seminars.

Esalen is a magnificent and magical place, with extraordinary views of the Big Sur mountains and the Pacific Ocean. The natural hot springs, or “baths” as they are called, remain an integral part of the Esalen experience. During the 1960s, Joan Baez was living in the area and Esalen hosted five of her famous folk festivals. “In addition to drawing thousands of local people to Esalen, these festivals, over the years, attracted people like George Harrison and Ringo Starr, Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, Joni Mitchell, Judy Collins, Lily Tomlin, Mama Cass, Pete Seeger, Arlo Guthrie, Paul Simon, Art Garfunkel, David Crosby, the Chambers Brothers, and others,” Murphy said.

Carolyn and I have both spent a lot of time taking workshops at Esalen. We took numerous workshops with Terence McKenna there together during the early 1990s, as well as with Colin Wilson and others. I have met many incredible people at Esalen over the years. In fact, it was at a workshop there that I attended in 1982 by Timothy Leary that I first met Carolyn’s daughter, and this is how I became friends with Carolyn.

In 1972 Murphy retired from actively running Esalen to do more writing. He has written a number of popular books, including In the Zone, The Psychic Side of Sports, The Kingdom of Shivas, and God and the Evolving Universe. Murphy’s 785-page book The Future of the Body: Explorations into the Further Evolution of Human Nature, which was published in 1992, is a “historical and cross-cultural collection of documentation of various occurrences of extraordinary human functioning such as healing, hypnosis, martial arts, yogic techniques, telepathy, clairvoyance, and feats of superhuman strength.”

Murphy is also a passionate golfer, and he has written two fictional books about the relationship between golf and human potential. He describes golf, with its mixture of solitude and intense focus, as creating in some people a sensory deprivation that is conducive to mystical epiphanies. Murphy’s 1971 novel, Golf in the Kingdom, is one of the bestselling golf books of all time.

In 1992 Golf in the Kingdom inspired The Shivas Irons Society, an organization that “explores the transformational potential of sport,” of which Murphy is the co-chairman of the advisory board. In 2010 film producer Mindy Affrime produced a feature film adaptation of Golf in The Kingdom, which was directed by Susan Streitfeld, and stars David O’Hara, Mason Gamble, Malcolm McDowell, and Frances Fisher.

Murphy currently resides in Mill Valley, California. At 92 years old, he remains on the board at the Esalen Institute, and he continues to be a key contributor to research projects at the Esalen Center for Theory and Research.

Some of the quotes that Michael Murphy is known for include:

Life is tough, then you die. The sooner you accept that and move on with your life, the better off you’ll be.

Then he began to speak. “Golf recapitulates evolution,” he said in a melodious voice, “it is a microcosm of the world, a projection of all our hopes and fears.

Just the thought of it hurts, but I truly believe that sometimes you have to be willing to break your own heart to save your soul.

A round of golf partakes of the journey, and the journey is one of the central myths and signs of Western Man. It is also a round: it always leads back to the place you started from.

The more I study [golf], the more I come to deeply love and admire athletic excellence and beauty. It is one of the great manifestations of the divine.

Carolyn and I have long appreciated the spiritual teachings of the philosopher, speaker, and writer Jiddu Krishnamurti.

Krishnamurti was born in 1895 in South India. He was described as a “sensitive and sickly” child, and his childhood years were difficult. Because Krishnamurti was often seen as “vague and dreamy,” people thought that he was cognitively impaired, and he was beaten regularly, at home by his father and in school by his teachers. However, he developed a special bond with nature during his childhood and this stayed with him throughout his life.

In 1909, while in early adolescence, Krishnamurti met a man named Charles Webster Leadbeater, who was part of a group called the Theosophical Society. This meeting was to change his life. The Theosophical Society is an esoteric religious movement that was founded in 1875 in New York by Russian mystic Helena Blavatsky and others. Leadbeater saw something special in Krishnamurti, and became convinced that he was destined to become a great spiritual teacher.

As a result, Krishnamurti was raised and educated by the Theosophical Society in Adyar, India, and they prepared him for what they believed him to be, the “vehicle” of the expected “World Teacher” or “Lord Maitreya.” In Theosophy, Lord Maitreya is an advanced spiritual entity, and master of ancient wisdom, who “periodically appears on Earth to guide the evolution of humankind.”

In 1911 the Theosophical Society established the Order of the Star in the East (OSE). The OSE was an international organization based in India that existed from 1911 to 1927. It was established by the leadership of the Theosophical Society to “prepare the world” for the arrival of a reputed messianic entity, the World Teacher or Lord Maitreya.

Krishnamurti was named as the head of the OSE, and senior Theosophists were assigned to various other positions. That same year Krishnamurti and his younger brother Nitya were taken to England by the Theosophical Society. Between 1911 and 1914, the brothers visited several other European countries, accompanied by Theosophist chaperones.

As a teenager, Krishnamurti described having psychic experiences, such as seeing the spirits of his late mother, and sister who had died in 1904. As Krishnamurti entered adulthood he embarked on a schedule of lectures in several countries, and he acquired a large following among the members of the Theosophical Society. Chapters of the OSE were formed in as many as forty countries.

In 1922 Krishnamurti and his younger brother Nitya traveled to California, where they stayed in Ojai Valley. During their stay in Ojai, Krishnamurti had a series of transformative psychological and spiritual experiences over a period of several months. Then, in 1925 his brother Nitya died, and this was a devastating event for Krishnamurti.

After years of controversy within the OSE, in 1929 Krishnamurti left his mantle and withdrew from the organization. He renounced his role, dissolved the Order with its following, and returned all of the money and property that had been donated for this work. He stated that he had made this decision after “careful consideration” during the previous two years. Krishnamurti moved away from the Theosophical Society because he came to realize that neither gurus nor organizations are required for attaining salvation, and he said that he had “no allegiance to any nationality, caste, religion, or philosophy.”

Krishnamurti spent the rest of his life traveling the world, speaking to large and small groups, and writing influential books. He also interacted with a number of other brilliant minds. In 1938 Krishnamurti was introduced to Aldous Huxley and the two became close friends for many years. In the early 1960s, Krishnamurti met physicist David Bohm, and the two men also became good friends and collaborated together. They started a common inquiry, in the form of personal dialogues — and occasionally in group discussions with other participants– that continued, periodically, over nearly two decades. Some of these intriguing discussions were published in a series of popular books.

In 1984 and 1985, Krishnamurti spoke to an audience at the United Nations in New York about peace. His 1985 talk, titled Why Can’t Man Live Peacefully on the Earth?

Krishnamurti is the author of over thirty books, including The Book of Life, The Awakening of Intelligence, The Beauty of Life, The First and Last Freedom, The Only Revolution, Krishnamurti’s Notebook, and The Ending of Time: Where Philosophy and Physics Meet, which includes some of his discussions with physicist David Bohm. Many of his talks and discussions have also been published and much is available online.

Krishnamurti was a lifelong vegetarian who exercised regularly and practiced yoga daily. He died in 1986 at the age of 90. Krishnamurti’s philosophy has remained popular in the years since his death; his books are in print, his foundations continue to maintain archives and disseminate his teachings, and his quotes are regularly shared social media.

Our dear friend Jai Italiaander became well acquainted with Krishnamurti. After spending five years in an ashram in Santa Rosa, Jai met someone at the ashram who took her to Ojai, where she became well acquainted with Krishnamurti, and his teachings became part of her life-long study of consciousness.

Some of the quotes that Krishnamurti is known for include:

You must understand the whole of life, not just one little part of it. That is why you must read, that is why you must look at the skies, that is why you must sing, and dance, and write poems, and suffer, and understand, for all that is life.

Emptiness comes as sunset comes of an evening, full of beauty, enchantment and richness; it comes as naturally as the blossoming of a flower.

You are the world and the world is you… If you as a human being transform yourself, you affect the consciousness of the rest of the world.

It is a waste of energy when we try to conform to a pattern. To conserve energy, we must be aware of how we dissipate energy.

To live in the eternal present there must be death to the past, to memory. In this death there is timeless renewal.

One is never afraid of the unknown; one is afraid of the known coming to an end… You can only be afraid of what you think you know.

It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society.

The ability to observe without evaluating is the highest form of intelligence.

Carolyn and I have long appreciated the writings of Lao Tzu, author of the Tao Te Ching, and have incorporated his philosophy into our lives.

Lao Tzu (or Laozi, and there are also around 10 other possible spellings of his name) was a semi-legendary ancient Chinese Taoist philosopher. The name Lao Tzu is a Chinese term that is usually translated as “the Old Master.”

It’s difficult to separate myth from fact about Lao Tzu; little is known about his life. Traditional accounts say that his original name was Li Er or Lao Dan and that he was born in the 6th century BC, in the village of Quren, which is in the state of Chu, a southern region in China.

It’s thought that Lao Tzu served as an archivist and scholar, an official who worked as a keeper of the imperial archives, for the Zhou court at Wangcheng. Zhho was a royal dynasty of China that lasted from 1046 BC to 256 BC, and Wancheng was an ancient Chinese city that today is known as Luoyang. This position as an archivist reportedly allowed Lao Tzu to access and study the classic works of his time.

Early accounts of Lao Tzu vary. In one account, it said that he was a contemporary of the Chinese philosopher and politician Confucius during the 6th or 5th century BC and that he met Confucius on one occasion, who was impressed by him, and Confucius mentions him in his writings. Another early account said that he was the court astrologer Lao Dan, who lived during the 4th century BC reign of the Chinese ruler Duke Xian of Qin.

In another account, it is said that Lao Tzu married and had a son who became a celebrated soldier. It is also thought that Lao Tzu never opened a formal school, but that he attracted many students and loyal disciples. In the later part of his life, he moved west and lived in an unsettled frontier region of China until the age of 80.

When Lao Tzu moved to this new region in the west, it is said in one account that a guard at the gate of this region asked him to record his wisdom for the good of the country before he could pass, and the text that he wrote was said to be the initial draft for the Tao Te Ching, although the present version includes additions from later periods.

The oldest surviving text of the Tao Te Ching so far recovered was part of the unearthed tomb of Guodian Chu Slips in 1993 and dates back to the Warring States period, which was an era in Chinese history characterized by warfare and lasted from 481 BC to 403 BC. The text of this early copy of the Tao Te Ching was written on bamboo slips, which was the main medium for writing documents prior to the introduction of the paper.

Some Western scholars think that the person known as Lao Tzu is a mythical character and that the Tao Te Ching was actually authored by a group of philosophers, not a single person, although more recent archeological discoveries have provided evidence that many Chinese scholars believe affirm the existence of a historical Lao Tzu.

The Tao Te Ching is a fundamental text for Taoism. Along with Confucianism and Buddhism, Taoism is one of the main currents of Chinese philosophy. Taoism is a philosophical or religious tradition that emphasizes living in harmony with the Tao. The word “Tao” doesn’t have a clear definition, because, according to the Tao Te Ching, “The Tao that can be expressed is not the eternal Tao.” However, the term generally means “way,” “path,” or “principle,” and in Taoism, it denotes something that is both the source and the driving force behind everything that exists. Some think of it as “God,” “the Great Spirit,” or “the Great Mystery,” but if it can be expressed in words, then by definition, it is not the Tao.

There are numerous myths about Lao Tzu. Some traditions worship Lao Tzu as a god and believe that he entered this world through a virgin birth, conceived when his mother gazed upon a falling star and that he remained in his mother’s womb for 62 years. According to this tradition he emerged from his mother’s womb as a grown man with a full grey beard. Other myths say that he was reborn 13 times after his first life, and in his last life, he lived for 990 years, traveling around China and teaching about the Tao.

Today there are numerous translations of the Tao Te Ching, and the influence of Taoism on Chinese culture and the Western world has been deep and far-reaching, influencing literature and the arts, as well as science. The Taoist perspective on natural elements, and observing how the natural world works, helped to create Chinese medicine. A search on Amazon currently reveals over 60 popular translations of the Tao Te Ching. Wayne Dyer created Living the Wisdom of the Tao, which contains the complete Tao Te Ching along with affirmations, and our friend Timothy Leary wrote a translation of the Tao Te Ching called Psychedelic Prayers.

Much of Carolyn’s artwork and poetry has been inspired by Taoism. Below are several of her Taoism-inspired paintings.

Some of the quotes that Lao Tzu is known for include:

The journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.

A good traveler has no fixed plans and is not intent on arriving.

Those who know do not speak. Those who speak do not know.

If you are depressed you are living in the past. If you are anxious you are living in the future. If you are at peace you are living in the present.

Care about what other people think and you will always be their prisoner.

Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished.

Do you have the patience to wait until your mind settles and the water is clear?

Silence is a source of Great Strength.

Music in the soul can be heard by the universe.

Carolyn and I have both really enjoyed the extraordinary artwork of Vincent van Gogh. The legendary Dutch post-impressionist artist is recognized as one of the greatest painters that ever lived, and he has become one of the most famous and influential figures in art history. Van Gogh’s paintings are among the most valuable in the world, and in many ways, he personifies the quintessential archetype of the mad and tormented artistic genius.

In the span of a decade, van Gogh created an astonishing 2,100 pieces of artwork. These pieces included landscapes, still lifes, portraits, and self-portraits, and they featured dramatic brushwork with bold and vivid colors. However, despite his immense talent, van Gogh was unsuccessful commercially, and this resulted in years of poverty and severe depression that ultimately led to his suicide. Recounting Van Gogh’s tragic life is extremely sad, and it’s so ironic that someone with such a profoundly unhappy life, with so many so-called “failures,” produced so many astoundingly beautiful works of art in such a short period of time.

Vincent Willem van Gogh was born in 1853, in the predominantly Catholic province of North Brabant in the Netherlands. He was born into an upper-middle class family; his father was a minister, and his mother was a religious woman who came from a prosperous family. His brother Theo, who was to play an important role in his life, was born in 1857, and he also had another brother and three sisters. Van Gogh was described as being a “serious,” “quiet,” and “thoughtful” child who was “passionate about drawing.”

In 1860 Van Gogh attended his village school, after being educated at home by his mother and a governess. Four years later Van Gogh went to a boarding school in Zevenbergen, where he had a difficult time and felt “abandoned.” In 1866 he attended a Middle School in Tiburg, where he was also “deeply unhappy.” Van Gogh didn’t like school but he became interested in art at a young age, and was encouraged to draw by his mother.

In 1869 Van Gogh’s uncle arranged for him to get a job as an art dealer in The Hague, and in 1873 he was transferred to the London branch of the art dealership. This was a happy time for Van Gogh, as he was making good money, and according to Theo’s wife, this was “the best year in Vincent’s life.”

However, after being rejected by a woman he admired, Van Gogh grew more isolated and religiously fervent. Throughout his life, romantic rejection and loneliness plagued Van Gogh. In 1875 he was transferred to an art dealership in Paris, where he wasn’t as happy, and he became resentful of how the dealers commodified artwork. He was fired from this position after a year.

In 1876 Van Gogh returned to England to work as a substitute teacher in a small boarding school in Ramsgate, which didn’t last long; he left to become a minister’s assistant and then to work in a bookshop. He wasn’t happy at any of these jobs and mostly spent his time doodling and translating passages from the Bible. Van Gogh immersed himself in Christianity and became increasingly religious. In 1877, Van Gogh went to live with his uncle, a theologian, who supported his desire to become a pastor, but he failed his theology entrance exam at the University of Amsterdam, and he also didn’t pass a three-month course in Protestant missionary near Brussels, Belgium.

In 1880, at Theo’s suggestion, Van Gogh began devoting more attention to his art, and he went to study with the Dutch artist Willem Roelofs, who persuaded him to attend the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. In 1880 Van Gogh registered at the Académie, where he studied anatomy and the standard rules of modeling and perspective.

In 1881, Van Gogh returned home to stay with his parents. That year his recently widowed cousin, Cornelia “Kee” Vos-Stricker, arrived for a visit, and they took long walks together. Van Gogh declared his love for her and proposed marriage, but she declined, with the words, “no, nay, never,” largely because of Van Gogh’s inability to support himself. Van Gogh was emotionally crushed. He journeyed to Amsterdam but Kee wouldn’t see him, and her parents wrote that his “persistence is disgusting.”

In 1882, Van Gogh’s second cousin Mauve introduced him to oil painting and lent him the money to set up a studio. Van Gogh hired people off the street to serve as models. He liked working in this medium and was able to continue with money from Theo. That same year Van Gogh began living with an alcoholic prostitute and her daughter, which his family disapproved of. The woman drowned herself in a river years later.

In 1885, during a two-year stay in Nuenen, Van Gogh completed numerous watercolors, drawings, and almost 200 oil paintings. His paintings consisted mainly of somber earth tones, particularly dark brown, without the vivid and iconic bold colors that distinguished his later work.

In 1885 Van Gogh’s work was exhibited for the first time, in the shop windows of an art dealer in The Hague. That year he moved to Antwerp, where he lived in poverty, ate poorly, and spent the money that Theo sent him on art supplies and models instead of food. Van Gogh spent time studying the artwork in museums and he broadened the colors in his palette. He also began drinking absinthe heavily and suffered from a series of venereal diseases.

In 1886 Van Gogh moved to Paris where he shared Theo’s apartment and continued his painting. However, conflicts between the two brothers arose, and by the end of that year Theo said that he found living with his brother to be “almost unbearable.” Van Gogh moved to a suburb of Paris, and in 1887 there was an exhibit of his work in Paris.

In 1888 Van Gogh moved to Arles, where he entered into one of his most prolific periods. Here, Van Gogh completed 200 paintings and more than 100 drawings and watercolors. That year the post-Impressionist painter Paul Gauguin visited Arles and the two painted together, but they didn’t get along well, and their relationship got worse over time. It was during this time that the bizarre incident that Van Gogh is probably most famous for occurred— the severing of his own left ear.

The exact sequence of events remains a mystery, but it is said that Van Gogh was hearing voices in his head on the night that he cut off his left ear with a razor. There was severe bleeding and he bandaged the wound. Then Van Gogh wrapped the ear in paper and delivered it to a woman at a brothel that he had frequented. He was found unconscious the next morning and was brought to a hospital where he was treated. Van Gogh had no recollection of the event. His hospital diagnosis was “acute mania with generalized delirium.” Theo visited him and he recovered. Gauguin left Arles and Van Gogh never saw him again.

Van Gogh gave his painting Portrait of Doctor Felix Rey to his physician. His doctor was not very fond of the painting and gave it away. In 2016 the painting was estimated to be worth more than $50 million.

In 1889 Van Gogh was placed in an asylum in Provence, France, where he continued his painting in a cell with barred windows. Flowing, swirling energies and blurring boundaries, such as in his iconic painting “The Starry Night,” characterize his work during this time.

In 1890 Van Gogh left the asylum and moved to a suburb of Paris near his doctor and Theo. Several months later Van Gogh shot himself in the chest with a revolver. There were no witnesses, and the shooting took place in the wheat field where he had just been painting. Van Gogh survived the shooting but died of an infection resulting from the wound around 30 hours later. According to Theo, his brother’s last words were, “The sadness will last forever.” He was buried in the municipal cemetery of Auvers-sur-Oise.

There has been much speculation as to the type of mental illness that Van Gogh suffered from and how this influenced his creativity. Many experts believe it was a type of bipolar disorder, while others have suggested temporal lobe epilepsy with bouts of depression. Whatever the etiology of the illness was, it was certainly a very high price that Van Gogh paid in order to bring us the glorious beauty that he did.

Van Gogh only sold one painting during his lifetime, Red Vineyard at Arles. The remainder of his more than 900 paintings were not sold or made famous until after his death when his reputation grew steadily among artists, art critics, dealers, and collectors. It’s so sadly ironic that Van Gogh suffered so much due to his lack of commercial success and romantic rejection, was considered a madman and a failure during his lifetime, and today he is regarded as one of the greatest artists who ever lived, as collective value to all of his work that is now estimated to be worth over 10 billion dollars.

Van Gogh’s paintings are located in many museums and art collections. The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam has many of his most iconic works. The museum houses the largest collection of his work worldwide, with 200 paintings, 400 drawings, and 700 letters. As one ascends through the museum, the artwork is presented in chronological order, and one can witness the transformation of his mind over time. More of Van Gogh’s work can be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and the National Gallery of Art in London. Through all his personal torment and darkness, Van Gogh’s ecstatic soul is miraculously singing to us.

Some of the quotes that Vincent Van Gogh is known for include:

I dream my painting and I paint my dream.

Be clearly aware of the stars and infinity on high. Then life seems almost enchanted after all.

…and then, I have nature and art and poetry, and if that is not enough, what is enough?

Normality is a paved road: It’s comfortable to walk, but no flowers grow on it.

I put my heart and soul into my work, and I have lost my mind in the process.

What am I in the eyes of most people — a nonentity, an eccentric, or an unpleasant person — somebody who has no position in society and will never have; in short, the lowest of the low. All right, then — even if that were absolutely true, then I should one day to show by my work what such an eccentric, such a nobody, has in his heart. That is my ambition, based less on resentment than on love in spite of everything, based more on a feeling of serenity than on passion. Though I am often in the depths of misery, there is still calmness, pure harmony and music inside me. I see paintings or drawings in the poorest cottages, in the dirtiest corners. And my mind is driven towards these things with an irresistible momentum.

If you truly love nature, you will find beauty everywhere.

The heart of man is very much the sea, it has its storms, it has its tides and in its depths it has its pearls too.