Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

Carolyn and I have admired the work of researcher, philosopher, and author Jean Houston, who was one of the principal founders of — and has been a leading voice in — the Human Potential Movement. She is the author of 26 books and is noted for her interdisciplinary perspective that combines extensive knowledge of history, culture, cutting-edge science, spirituality, and human development. Her philosophy, strategies, and perspective are valued by heads of state and government officials in countries throughout the world.

Jean Houston was born in 1937 in New York City. Her father was a comedy writer who developed material for stage, television, and movies, as well as for comedians, such as Bob Hope, Edgar Bergen, and George Burns. Due to her dad’s career, as a child, Houston moved around a lot, and she attended 29 different schools before the age of twelve.

In 1958, Houston graduated from Barnard College in New York City with a Bachelor’s degree. She subsequently earned two doctorates: a Ph.D. in psychology from Union Graduate School in Cincinnati, Ohio, and a Ph.D. in religion from the Graduate Theological Foundation in Sarasota, Florida. Houston has also been the recipient of a number of honorary doctorates over the years.

In the early 1960s, Houston became one of the first researchers to study the effects of psychedelic drugs in a government-sanctioned research project. In 1963, British writer Aldous Huxley, whom I wrote a profile about a while back, requested to meet with her about her research, and their meeting had an important influence on her work, she told me when I interviewed her. In her research studies, she also became acquainted with writer and researcher Robert Masters, and they became romantically involved. In 1965, Houston and Masters married and became a powerful team.

In 1966, Houston and Masters published their book The Varieties of the Psychedelic Experience, which became a classic in the field, and in 1968 they published the book Psychedelic Art. After the government banned psychedelic research that year, the couple shifted their focus to exploring other ways of achieving altered states of consciousness. Together they created the Foundation for Mind Research in Pomona, California, where they conducted research into the interdependence of body, mind, and spirit.

From 1965 to 1972, Houston taught at Marymount College in Tarrytown, New York. In 1972, Houston and Masters published their book Mind Games, which detailed their findings that guided imagery and specific programs of bodily movement could “reprogram the brain toward more integrated ways of experiencing the world.” John Lennon of the Beatles called Mind Games, “one of the two most important books of our time.”

In 1975, Houston chaired the United Nations Temple of Understanding Conference of World Religious Leaders, and in 1977 she served as president of the Association for Humanistic Psychology. Houston’s interest in anthropology brought her into a close association with anthropologist Margaret Mead, who became the president of the Foundation for Mind Research, and who lived with Houston and Masters for several years before her death in 1978.

In 1979, Houston chaired the U.S. Department of Commerce symposium for government policymakers. In 1982, Houston began teaching a seminar based on the concept of “the ancient mystery schools,” which she taught at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, which I wrote about in a previous profile, and other educational centers.

In 1996, during the first term of the Clinton administration, First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton invited Houston to work with her in the White House as an advisor. Houston facilitated creative thinking, and role-playing exercises, such as having Clinton engage in imaginary dialogues with Gandhi and Eleanor Roosevelt, and these exercises became an important part of Clinton’s writing process when she was working on her book It Takes a Village.

However, this relationship between Houston and Clinton developed into a public controversy when the media began reporting on it, and labeled Houston “Hilary’s guru” and the “First Lady’s Spiritual advisor.” Houston said that as a result of the media coverage, she “suddenly found herself the hapless butt of a thousand gags.” Houston was compelled to explain that “We were using an imaginative exercise to force her ideas, to think about how Eleanor would have responded to a particular problem,” and that she had “never been to a séance.”

Houston has worked at both the grassroots and government levels, offering her human potential development skills to local and international development agencies as they attempt to bring about cultural growth and social change, such as collaborating with UNICEF in Bangladesh and elsewhere. As an advisor to UNICEF in human and cultural development, Houston has worked around the world helping to implement some of their extensive educational programs. In 1999, Houston traveled to Dharamsala, India as a member of a group chosen to work with the Dalai Lama in a learning and advisory capacity.

In 2008, a non-profit, leadership training organization, the Jean Houston Foundation, was formed to teach “social artistry” in the United States and overseas, in order to promote positive social change. The organization works to find “innovative solutions to critical local and global issues,” and this is accomplished “through training, research, consultation, leadership, and guidance.” This training has been conducted in Albania, the Eastern Caribbean, Kenya, Zambia, Nepal, and the Philippines.

Some of the popular books that Houston has written include: The Possible Human, A Passion for the Possible, Life Force, A Mythic Life: Learning to Live Our Greater Story, and Manual of the Peacemaker. The late philosopher and visionary inventor Buckminster Fuller, who I wrote a profile about several weeks ago, said, “Jean Houston’s mind should be considered a national treasure.”

I interviewed Jean Houston in 1994 for my book Voices from the Edge. Here are some excerpts from our conversation:

David: Could you tell us about the work you did with the Apollo astronauts?

Jean: I was one of those who was fortunate enough to work with NASA at the time of the moon landing. I was doing work that had to do with helping astronauts remember what they saw when they were on the moon, because they didn’t remember a great deal. I tried everything: I hypnotized them, I did various kinds of active imagination exercises, I taught them to meditate, I yelled at them— that’s what worked.

Finally, one of them said, “You know, Jean, you’re asking the wrong question. It’s not what we saw on the moon, it’s what we saw coming back to earth. Seeing that beautiful blue and silver planet gave us a feeling of such nostalgia for what the world can be. My hand hit the stereo button, and the music of Camelot came on.” Imagine that! I have seen that picture of the earth from outer space in a leper’s hut in India. I was present in China when a Chinese peasant took a photo of Mao off the wall and replaced it with a photo of the earth.

David: What do you think happens to consciousness after biological death?

Jean: I’ve nearly died four times. Once was when I was nineteen. I used to jump out of planes, and I had an experience of my chute not opening. My whole life went by. Not every pork chop, but all the major events at their own time. The adrenaline rush turned on life again. Another time, I nearly died of typhoid fever in Crete. It was very pleasant. I found myself leaving the fifth-class hotel and the room of this reality, and going into the next. A light went out here, a light went up there— and there was my car waiting. But I was a young kid, and I said, “I’m not ready, no!” and there was this tremendous psychic effort to pull myself back. I’m convinced of continuity— I can’t say reincarnation, because the universe is so complex. We have many different agendas and opportunities, but consciousness, at some level, deeply continues.

When I was in one of Professor Paul Tillich’s courses, he kept referring to a word that was central to his theology, and that word was “wacwum.” We theological students met afterward, and we would spin out epistemologies, the phenomenology and the existential roots of the “wacwum.” And we had a whole book by the end of the term. Finally, they asked me to ask the great man a question, so I put my hand up. When he said, “Yes?” I forgot my question, so I asked him one of blithering naiveté. I asked, “How do you spell “wacwum”? “Yes, Miss Houston,” and he spelled on the board “v-a-c-u-u-m.” That’s what we are! If you take a body and scrunch it together and get rid of all the empty space, what have you got what for every human being? A grain of rice!

David: What is your perspective on God?

Jean: Nicholas of Cusa said that “God is a perfect sphere, whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere.” I believe that we are always available to the omnipresent grace, and that part of our life is about discovering that we contain the God-stuff in embryo. I like to use a little bit of metaphysical science fiction and say that where we are on this planet is the skunkworks at the corner of the universe. We’re in God school, learning to become co-creators.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of author Michael Murphy, who has been a key figure in the human potential movement and is co-founder of the Esalen Institute in Big Sur.

Michael Murphy was born in 1930 in Salinas, California. His father was Irish and his mother was Basque. In 1950 Murphy began studying at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, where he was enrolled in a pre-med program. One day Murphy accidentally wandered into a class on comparative religions, that was to change the course of his life. This accidentally attended lecture so inspired Murphy’s interest in Eastern and Western philosophy and spirituality that he enrolled in the class, and soon began practicing meditation.

In 1951, during a meditation experience by Lake Lagunita in Palo Alto, Murphy experienced a transformative vision that caused him to drop out of the pre-med program at Stanford with “a new purpose life.” Murphy switched his major to psychology, graduating from Stanford with a psychology degree in 1952.

After graduating from Stanford, Murphy spent two years in the U.S. Army, stationed in Puerto Rico as a psychologist. Then Murphy returned to Stanford, where he spent two quarters studying philosophy in graduate school, before embarking on a trip to India in 1956.

Between 1956 and 1957 Murphy practiced meditation at the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in Puducherry, India, where there was an established spiritual community. After this, he returned to California, and in 1960, while in residence at the Sri Aurobindo Ashram Fellowship in San Francisco, Murphy met Dick Price, who was also a Stanford University graduate, and they shared a common interest in psychology.

In 1962, Murphy and Price founded the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California on 127 acres of property that was owned by Murphy’s family. The grounds of the institute were originally home to a Native American tribe known as the Esselen, and carbon dating of artifacts found in this location has indicated a human presence there as early as 2600 BCE. The property was first homesteaded in 1882, and the hot springs there became a tourist attraction that was frequented by people seeking relief from physical ailments. In 1910 Murphy’s grandfather, a physician named Henry Murphy, purchased the property, and continued the hot springs business there.

The Esalen Institute became a retreat center that focuses on humanistic alternative education, and which many people consider to be the birthplace of the human potential movement. The organization has concentrated on teaching classes and workshops that explore personal growth, meditation, massage, ecology, yoga, psychology, the mind-body connection, and spirituality.

Some of the many incredible people who have taught at the Esalen Institute over the years include Abraham Maslow, Alan Watts, Timothy Leary, Fritz Perls, Nick Herbert, Robert Anton Wilson, Joseph Campbell, John Lilly, and Stanislav Grof. On average, more than 15,000 people a year from all over the world attend Esalen classes and seminars.

Esalen is a magnificent and magical place, with extraordinary views of the Big Sur mountains and the Pacific Ocean. The natural hot springs, or “baths” as they are called, remain an integral part of the Esalen experience. During the 1960s, Joan Baez was living in the area and Esalen hosted five of her famous folk festivals. “In addition to drawing thousands of local people to Esalen, these festivals, over the years, attracted people like George Harrison and Ringo Starr, Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, Joni Mitchell, Judy Collins, Lily Tomlin, Mama Cass, Pete Seeger, Arlo Guthrie, Paul Simon, Art Garfunkel, David Crosby, the Chambers Brothers, and others,” Murphy said.

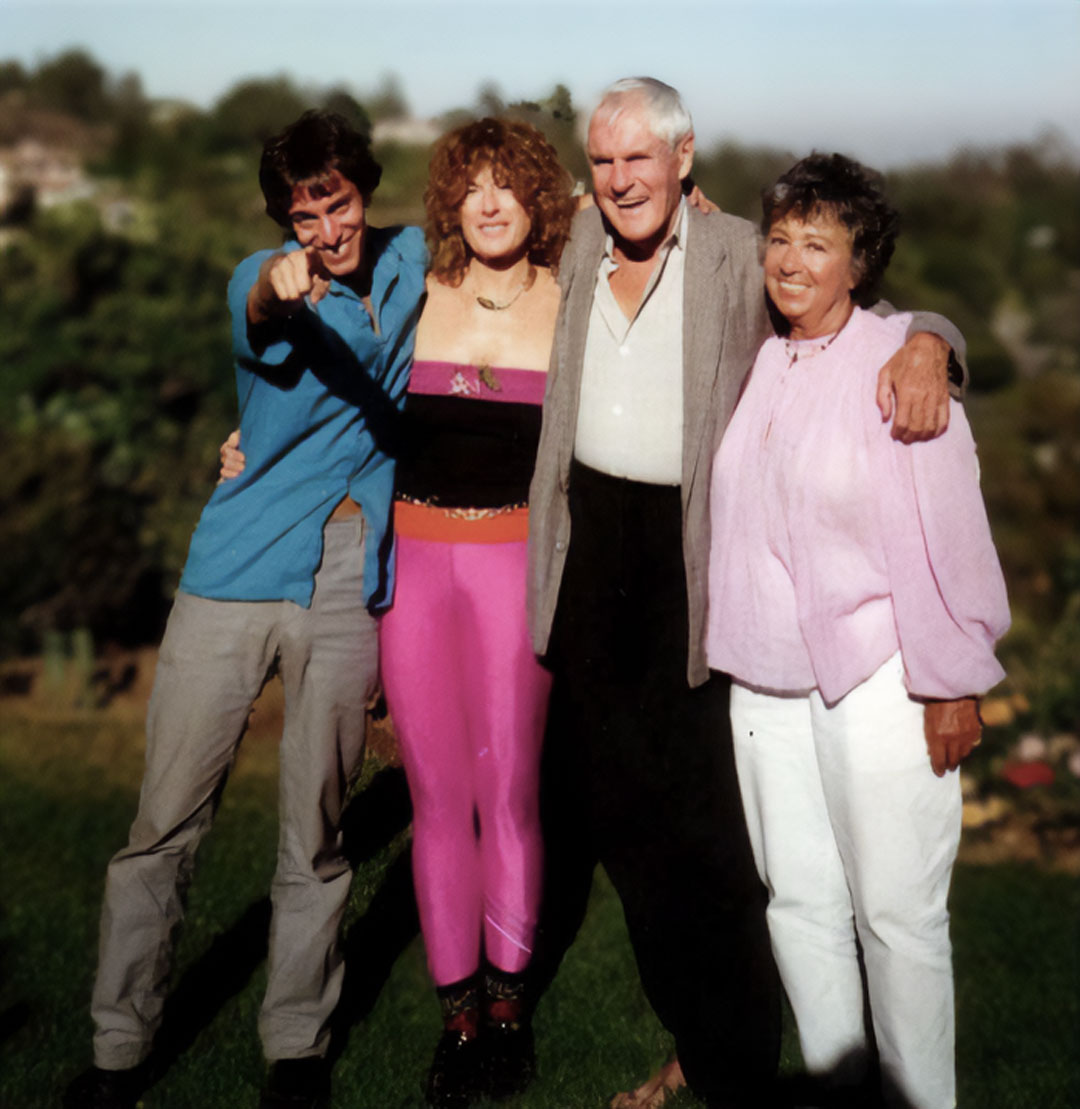

Carolyn and I have both spent a lot of time taking workshops at Esalen. We took numerous workshops with Terence McKenna there together during the early 1990s, as well as with Colin Wilson and others. I have met many incredible people at Esalen over the years. In fact, it was at a workshop there that I attended in 1982 by Timothy Leary that I first met Carolyn’s daughter, and this is how I became friends with Carolyn.

In 1972 Murphy retired from actively running Esalen to do more writing. He has written a number of popular books, including In the Zone, The Psychic Side of Sports, The Kingdom of Shivas, and God and the Evolving Universe. Murphy’s 785-page book The Future of the Body: Explorations into the Further Evolution of Human Nature, which was published in 1992, is a “historical and cross-cultural collection of documentation of various occurrences of extraordinary human functioning such as healing, hypnosis, martial arts, yogic techniques, telepathy, clairvoyance, and feats of superhuman strength.”

Murphy is also a passionate golfer, and he has written two fictional books about the relationship between golf and human potential. He describes golf, with its mixture of solitude and intense focus, as creating in some people a sensory deprivation that is conducive to mystical epiphanies. Murphy’s 1971 novel, Golf in the Kingdom, is one of the bestselling golf books of all time.

In 1992 Golf in the Kingdom inspired The Shivas Irons Society, an organization that “explores the transformational potential of sport,” of which Murphy is the co-chairman of the advisory board. In 2010 film producer Mindy Affrime produced a feature film adaptation of Golf in The Kingdom, which was directed by Susan Streitfeld, and stars David O’Hara, Mason Gamble, Malcolm McDowell, and Frances Fisher.

Murphy currently resides in Mill Valley, California. At 92 years old, he remains on the board at the Esalen Institute, and he continues to be a key contributor to research projects at the Esalen Center for Theory and Research.

Some of the quotes that Michael Murphy is known for include:

Life is tough, then you die. The sooner you accept that and move on with your life, the better off you’ll be.

Then he began to speak. “Golf recapitulates evolution,” he said in a melodious voice, “it is a microcosm of the world, a projection of all our hopes and fears.

Just the thought of it hurts, but I truly believe that sometimes you have to be willing to break your own heart to save your soul.

A round of golf partakes of the journey, and the journey is one of the central myths and signs of Western Man. It is also a round: it always leads back to the place you started from.

The more I study [golf], the more I come to deeply love and admire athletic excellence and beauty. It is one of the great manifestations of the divine.

I began reading Carl Jung’s writings when I was in high school, and when I first met Carolyn, Jung’s work came up in our discussions a lot.

Carl Gustav Jung was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, who helped to revolutionize the field of psychology. Born in 1875, Jung has been described as a solitary and introverted child, with early aspirations to become a preacher or minister. However, after studying philosophy as a teenager, Jung decided against those religious aspirations and decided to pursue a career in psychiatry at the University of Basel instead.

In 1900 Jung moved to Zürich and began working at the Burghölzli psychiatric hospital, where he developed a relationship with the Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud. Jung and Freud became close friends and built a strong professional association; for six years they cooperated in their work. However, in 1912 a split between these two intellectual titans developed when Jung published a manuscript titled Psychology of the Unconscious. This historic book created a theoretical divergence between the two men; after this their personal and professional relationship was damaged, and over the years they became increasingly bitter toward one another.

In a nutshell, Jung believed that there was more to the unconscious mind than Freud. According to both Freud and Jung, the unconscious mind is the mental reservoir of emotions, memories, and brain processes that are outside of our conscious awareness; yet influence our thoughts, desires, dreams, and actions. One basic difference between Freud’s and Jung’s theories of the unconscious mind was that Freud believed that it is purely the result of our personal development, while Jung believed that there was also a transpersonal dimension to it, what he called “the collective unconscious,” that was shared by all of humanity.

Jung saw evidence for the collective unconscious among the common elements found around the world in dreams, visions, myths, fairy tales, art, and other forms of cultural expression— what he called “archetypes.” Archetypes are those images, figures, character types, settings, and story patterns that, according to Jung, are universally shared by people across cultures.

In mainstream psychology, Jung is known for introducing many commonly used concepts to the field, and that have also been adopted by the culture at large — such as his models of psychological types, and his notions of the anima and animus, the Self, the shadow, and introversion and extroversion. Another idea that Jung developed that Carolyn and I have both found useful is the notion of “synchronicity.” Synchronicity is the coincidental occurrence of events that seem meaningfully related but cannot be explained by conventional mechanisms of causality. Synchronicities are those magic moments of strange association that just seem too personally meaningful to be mere coincidence — implying that we have some deep, psychic interconnection with the universe that can’t be easily explained through mechanistic science.

In addition to his work in psychology, and his prolific writing, Jung was also an artist, a builder, and a skillful craftsman. He built a small castle with 4 towers on the shore of Lake Zürich, known as the Bollingen Tower. Jung was known to have mystical, visionary, and psychic experiences. His psychological experiments between 1915 and 1930, where he engaged his mind with what he called the “mythopoetic imagination,” resulted in a series of “visions” or “fantasies” that were recorded as art and text in an illuminated calligraphic volume that became known as The Red Book. Hidden for years in a Swiss bank vault, this legendary manuscript was published posthumously in 2009. I’ve spent many an hour spellbound by this remarkable book; it’s a beautiful artwork and powerful spiritual insights.

Jung died in 1961. The last book that he wrote, Man and his Symbols, was published 3 years after he died. Princeton University Press published a 20-volume set titled The Collected Works of C.G. Jung, which contains Jung’s dissertation, essays, lectures, and letters from 1902 until his death. A number of his books weren’t published until after he died, and some of Jung’s manuscripts remain unpublished to this day.

Jung’s influence can be seen throughout Carolyn’s work. For example, an entry in Carolyn’s Alchemy of Possibility oracle is titled “Synchronicity,” and Carolyn’s painting Reflecting on my Shadow expresses Jung’s concept of the shadow — that dark side of the unconscious mind, the self’s emotional blind spot, which is composed of repressed ideas, weaknesses, desires, instincts, and shortcomings.

Some quotes that Carl Jung is remembered for include:

Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life, and you will call it fate.

The meeting of two personalities is like the contact of two chemical substances: if there is any reaction, both are transformed.

I am not what happened to me, I am what I choose to become.

A dream that is not understood remains a mere occurrence; understood it becomes a living experience.

Who looks outside, dreams; who looks inside, awakes.

Photo by Bettmann

British writer, philosopher, and social satirist Aldous Huxley’s work has had a profound impact on Carolyn and I, and our dear friends Oz Janiger and Laura Huxley told us wonderful stories about their precious time with him.

Aldous Leonard Huxley was born in 1894 in Surrey, England. He was born into an intellectually active family; his father was a schoolteacher and writer, and his mother founded an independent girls’ boarding and day school. Aldous was the grandson of the famous zoologist Thomas Huxley, who was an early advocate for Darwin’s theory of evolution, and his brothers Julian and Andrew became noteworthy biologists.

Aldous’ father, Leonard Huxley, had a well-equipped botanical laboratory where Aldous began his science education as a child. His brother Julian described him as someone who “frequently contemplated the strangeness of things.”

Aldous faced some serious challenges as a teenager. In 1908 his mother died, and in 1911 he contracted an eye disease that caused the surface of his eyes to become inflamed. This ocular inflammation left him almost blind for around three years, and then he partially recovered, with one eye just capable of light perception, and the other with about 5 percent of normal vision. Unable to pursue a career in medicine, as he had initially intended, due to his loss of sight, Huxley studied English literature at Oxford from 1913 to 1916.

After graduating from Oxford, Aldous taught French for a year at Eton College in Berkshire. One of his students at the time was a young fellow named Eric Blair, who also went on to become a well-known writer; he took the pen name George Orwell and wrote the classic dystopian novel 1984.

In 1916 Aldous edited the Oxford Poetry journal, and he completed his first (although unpublished) novel at the age of 17. In 1921 Aldous published his first novel, Crome Yellow, which, like the novels that followed— Antic Hay in 1923, Those Barren Leaves in 1925, and Point Counter Point in 1928, were social satires.

In 1919 Aldous married his first wife, Maria Nys, and they had one child together, Matthew (who Carolyn and I met at a conference during the 1990s). Aldous and Maria lived with Matthew in Italy during the 1920s, where Aldous would spend time with his friend, English novelist and poet D. H. Lawrence.

In 1932 Aldous published his most well-known work, Brave New World, a dystopian novel about a World State in the future, where citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hierarchy. The book has since become a classic of modern literature— it ranked number 5 on a list of the 100 best-selling English-language novels of the 20th Century — and carried a profound warning about the dangers of social control that seem especially relevant today.

In 1937 Aldous moved to Los Angeles with his wife Maria, where he worked as a screenplay writer for Hollywood films. Aldous received screen credit for Pride and Prejudice in 1940, and he worked on a number of other films, including Jane Eyre in 1944. In 1955 Aldous’ wife Maria died.

Aldous grew interested in philosophical mysticism and in 1945 he published The Perennial Philosophy, which explores the common ground between Eastern and Western mysticism. Our beloved friend Laura Huxley first met Aldous in 1948, when she was pursuing an idea for a film, and although the film was never produced, they stayed close and were married in 1956. Laura was married to Aldous for the last 7 years of his life.

In 1953 Canadian psychiatrist Humphry Osmond introduced Aldous to a psychedelic medicine, mescaline, and he had a powerful mystical and transcendent experience that became the basis for his revolutionary book The Doors of Perception. It’s a slim volume, just 63 pages, but it had a powerful cultural impact and is generally regarded as one of the most important books on psychedelic mysticism. The popular rock band The Doors took their name from the title of Huxley’s book.

In 1962 Aldous published his final novel, Island, a utopian fantasy about a shipwrecked journalist on a fictional island, which incorporates the insights that he gained from his mystical experiences, and provides a wonderful alternative future to his dystopian vision in Brave New World. During his lifetime, Aldous published more than 50 books, and a large selection of poetry, short stories, articles, philosophical treatises, and screenplays.

Aldous died in 1963, on the same day that John F. Kennedy was assassinated. On his deathbed, Aldous asked Laura to administer LSD to him and he died while undergoing a psychedelic experience, as Laura read to him from The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Laura wrote about this experience, and her final days with Aldous, in her much-loved book This Timeless Moment.

Laura shared a favorite story with me about Aldous. She told me about this one time that Aldous was at a meeting of professional scientists, and how he was asked what final words of advice he could offer after a lifetime of inquiry. His response was, “I’m very embarrassed because I worked for forty years. I studied everything around. I did experiments. I went to several countries. And all I can tell you is to be just a little kinder to each other.”

Some of the quotes that Aldous is known for include:

After silence, that which comes nearest to expressing the inexpressible is music.

I wanted to change the world. But I have found that the only thing one can be sure of changing is oneself.

Most human beings have an almost infinite capacity for taking things for granted.

The more powerful and original a mind, the more it will incline towards the religion of solitude.

That men do not learn very much from the lessons of history is the most important of all the lessons that history has to teach.

Consistency is contrary to nature, contrary to life. The only completely consistent people are the dead.

The secret of genius is to carry the spirit of the child into old age, which means never losing your enthusiasm.

There are things known and there are things unknown, and in between are the doors of perception.

I wish so much that I had had an opportunity to interview Aldous, but I was only 2 years old when he died.

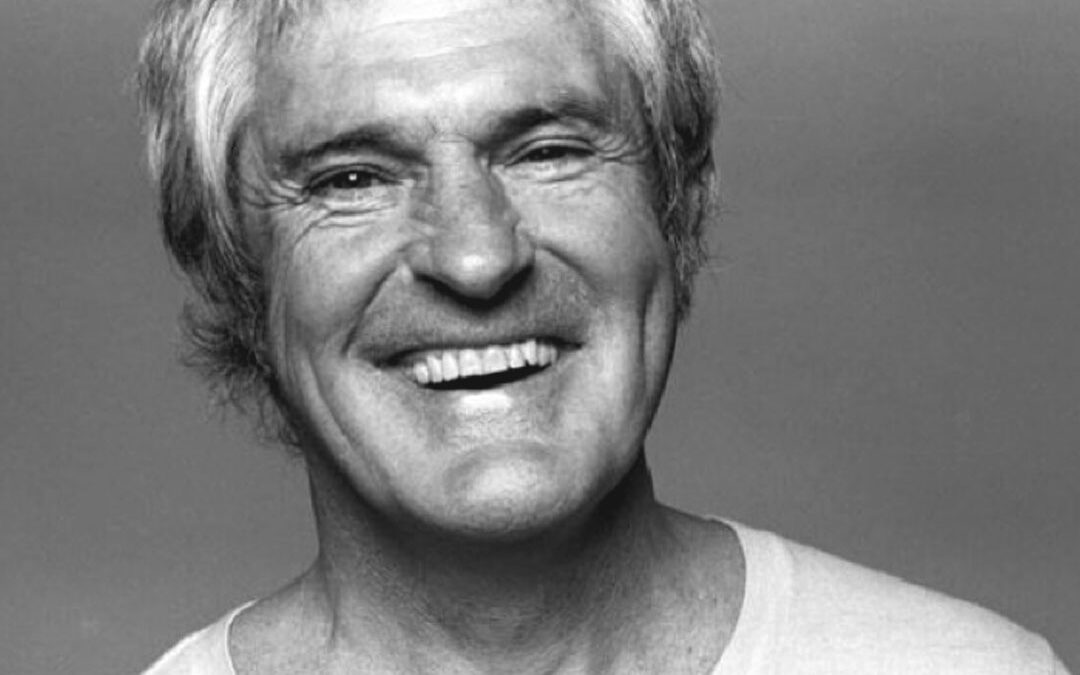

During the early 1990s Carolyn and I visited the late psychologist Timothy Leary a number of times at his home in Beverly Hills. Timothy was a good friend and a great inspiration, as well as a public icon of great controversy and one of the most influential psychologist-philosophers of the twentieth century. He was certainly one of the most brilliant, charming, and funniest people that I ever met.

Because of the sensationalized media attention that Timothy received, many of his accomplishments have been obscured and his image distorted in many people‘s minds. Timothy was a successful research psychologist, who received his Ph.D. from U.C. Berkeley, and was on the distinguished faculty at Harvard University from 1959 to 1963. The Annual Review of Psychology called his book Interpersonal Diagnosis of Personality, “the best work in psychotherapy” in 1957, and it remains a standard text in its field to this day.

When Timothy’s studies into controversial methods for altering consciousness lead to his dismissal from the prestigious university in 1963, he continued his research into visionary states at the Millbrook estate in New York, working with many influential writers, artists, scientific researchers, and philosophers. Timothy began traveling around the country— appearing at peace rallies, giving public lectures at universities, spreading messages of hope and cognitive freedom— and he became one of the most popular counterculture figures in America during the 1960s.

Timothy‘s influential public appearances, books and lectures, made him popular among young people and feared by the cultural establishment, because of his message to “drop out” from mainstream society. President Richard Nixon called him “the most dangerous man alive,” and he was sentenced to ten years in prison for less than a half an ounce of cannabis in 1970. Around eight months later Tim escaped from prison, and after being chased around North Africa and Europe by government agents for several years, and spending more time in prison, he was paroled by California governor Jerry Brown in 1976.

Throughout all his persecution, escape and capture, Timothy never lost his sense of optimism, or his sense of humor, and it is rare to find a photograph of Tim in which he isn’t smiling broadly. Timothy’s brave and upbeat approach to his own dying process was every bit as instructive and inspiring as his approach to life had always been. When Tim learned that he had terminal cancer, he announced that he was “thrilled and ecstatic” to be entering the mystery of death, and he made his final year on this planet a great celebration.

Timothy will certainly be remembered as one of the most original and creative philosophers of our time. He is the author of more than twenty-five books and many of his recorded lectures can be found online. Timothy was buzzing with lively electrical energy whenever we were around him, and his good-humored optimism was contagious. He had a wonderful ability to make people around him feel good about themselves. Timothy once said to me, “You have a very healing face. You radiate a kind of quiet joy. It’s amazing.” I was glowing for days after he said that to me, but most of all though, he made us laugh.

I interviewed Timothy twice, in 1989 and again in 1996, a few months before he left this world. Here are some excerpts from my conversations with him:

David: What kind of insight do you think we can gain from exploring the molecular and atomic realms?

Timothy: . . .The greatest wisdom is always housed in the smallest package. I think I even said that in the Psychedelic Prayers twenty-eight years ago. Look at the DNA code. The DNA code is invisible, and yet the DNA code has enough information to build you an Amazon rainforest, or build a hundred David Browns. I mean it’s there. The point is certainly obvious. We’ve now learned that the atom is not just a bunch of billiard balls going around Bohr’s solar system. The atom, we have every reason to expect, is charged with enormous miniaturized information. . .

David: What have you gained from your illness, and how has the dying process affected you?

Timothy: When I discovered that I was terminally ill I was thrilled, because I thought, “Now the real game of life begins. Oh boy! It’s the Super Bowl!” I entered into the real challenge of how to live an empowered life, a life of dignity. How you die is the most important thing you ever do. It’s the exit, the final scene of the glorious epic of your life. Death is loaded with paradox and taboo, so it’s hard for me to be thinking this through, even though I’m involved in the process of dying full-time. Do you follow my confusion? I can not exaggerate the power of this taboo about dying. It’s spooky, it’s something we’re supposed to be frightened of. Death is something symbolized by Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

David: What has been the secret, all these years, to your undying sense of courage and optimism?

Timothy: It’s common sense. It’s all common sense and fair play. See, because fair play is common sense. It’s a very obvious approach to life.

My interviews with Tim appear in my book “Mavericks of the Mind,” which also contains my interview with Carolyn.