Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

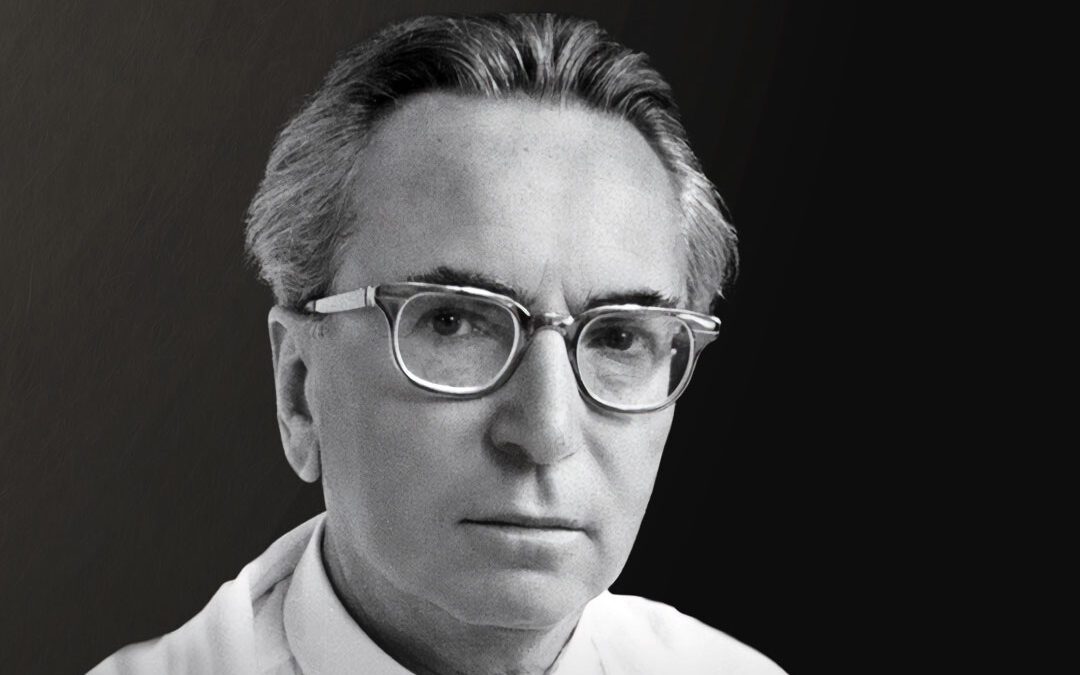

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of Austrian neurologist, psychologist, philosopher, and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl, who founded the school of existential and humanistic psychotherapy known as logotherapy, which describes a search for life’s meaning as the central human motivational force. His bestselling, autobiographical book Man’s Search for Meaning which is based on his experiences in the Nazi concentration camps, and his remarkable ability to triumph over profound tragedy, has been a powerful inspiration to millions of people.

Viktor Emil Frankl was born in 1905 in Vienna, Austria. He was born into a Jewish family and was the middle child of three children. His father was a civil servant for the Austrian government, holding positions in the Ministry of Social Service, and his mother was a homemaker. Both of Frankl’s parents were well-educated and valued learning, fostering a supportive environment for his intellectual development.

As a child, Frankl was curious, reflective, and driven by a deep desire to understand the human mind and the world around him. His family engaged in lively intellectual discussions, which fostered his early interest in philosophy and psychology.

Frankl attended a type of secondary school in Vienna known as “the Gymnasium,” where he received his early education. He attended the Wiener Wissenschaftliche Schule, a prominent academic institution. This rigorous academic environment played a significant role in shaping his intellectual development. In junior high school, Frankl began taking night classes in psychology, and as a teenager, he started a correspondence with Sigmund Freud.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 brought significant hardships to Austria, and consequently economic struggles for Frankl’s family. However, despite these challenges, Frankl excelled in school. In 1923, he graduated from high school and was accepted at the University of Vienna, where he studied medicine and focused on neurology and psychiatry. Frankl’s early interest in psychiatry was deeply influenced by Freud’s work. In 1930, he earned a Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) degree from the University of Vienna.

During this period, Frankl became involved with the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, and he shifted away from Freud’s school of thought towards Alfred Adler’s psychology, although he later distanced himself from both of these thinkers to develop his ideas. Frankl began writing and publishing on psychology and he developed an early version of his concept of “will to meaning,” which laid the groundwork for his later logotherapy.

Logotherapy is a form of existential psychotherapy that emphasizes the human search for meaning as the central motivation in life. Rather than focusing on past experiences or conflicts, logotherapy helps individuals find purpose in their present circumstances, even in suffering. It asserts that life has inherent meaning, and by discovering or creating this meaning, individuals can overcome psychological distress and find fulfillment. Frankl’s approach contrasts with Freud’s pleasure principle, as it centers on the “will to meaning” rather than the pursuit of pleasure or power.

In the early 1930s, Frankl began working with suicidal patients, particularly teens, and he ran youth counseling centers in Vienna, where his work was highly successful. Additionally, Frankl worked in various hospitals, refining his approach to treating depression and existential crises. In 1937, he opened a private practice in Vienna, specializing in neurology and psychiatry. From 1940 to 1942 Frankl was head of the Neurological Department of Rothschild Hospital. However, with the rise of Nazi Germany, Frankl faced increasing persecution for being Jewish.

Frankl decided to stay in Vienna during the Nazi occupation rather than flee to the United States. In 1941, he obtained a visa to leave Austria, but he struggled with whether to abandon his parents, who could not leave. Frankl unexpectedly found clarity— when he saw a piece of marble his father had saved from a destroyed synagogue. The marble had engraved upon it a portion of the Ten Commandments that read: “Honor your father and your mother.” This powerful moment convinced Frankl to stay with his parents in Vienna, a decision that led to his eventual deportation to the concentration camps.

In 1942, Frankl and his family were deported to the concentration camps, where most of his family, including his wife, parents, and brother were killed. Frankl was first deported to Theresienstadt in 1942, along with his family. Later, in 1944, he was transferred to Auschwitz, where he endured severe physical and profound emotional hardships. He was then moved to other camps, where he continued to struggle for survival until his liberation in 1945.

Miraculously, Frankl not only survived, but during his imprisonment, he reflected on the power of finding meaning in suffering. Remarkably, he discovered mental techniques for transcending suffering, even in the most horrific of circumstances. Throughout his time in the concentration camps, Frankl found solace in maintaining a sense of meaning and purpose, which strengthened his ideas about the power of finding meaning in even the worst situations, and this formed the basis for his logotherapy theory. After his liberation in 1945, Frankl wrote his seminal book, “Man’s Search for Meaning,” which was published in 1946, and detailed his experiences and how he triumphed over unbelievable horrors.

That same year Frankl was appointed head of the Vienna Neurological Policlinic, a position he held until 1970. In 1947, he remarried and resumed his medical and academic career, becoming a key figure in existential psychotherapy. In 1948, he earned a Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Vienna. His doctoral thesis focused on the relationship between existential philosophy and psychiatry.

In 1955, Frankl was appointed as a professor at the University of Vienna, and his ideas about meaning, purpose, and mental health were increasingly embraced in both academic and clinical circles. By 1959, his book Man’s Search for Meaning gained greater international acclaim; it was translated into multiple languages and became a key text in existential psychology. Frankl toured extensively, lecturing at prestigious universities worldwide, including Harvard University. In 1961, he also became a professor at the United States International University in San Diego.

In 1977, Frankl became a professor at the University of Dallas in Texas, and his ideas were increasingly applied in various fields, including education, philosophy, and counseling. Frankl continued lecturing extensively across Europe, the Americas, and Asia, receiving numerous honors and awards for his contributions to psychotherapy — such as the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art in 1986, recognizing his lifelong contributions — as well as honorary doctorates from various universities.

Frankl’s influence extended beyond psychology, impacting fields like education and spiritual counseling. While Frankl was not overtly religious, his views were influenced by spiritual themes, emphasizing the importance of transcending personal limitations and circumstances. Frankl believed in a dimension beyond the material, referring to a “spiritual unconscious” and often highlighting the significance of values, responsibility, and a connection to something greater than oneself. He saw spirituality as essential to psychological well-being, with logotherapy focusing on the spiritual need for meaning as a fundamental human drive.

Frankl remained active and continued to influence psychology and philosophy, and he continued to write and contribute to academic discussions on existential psychology and the human search for meaning. His health declined towards the mid-1990s, and in 1997 Frankl passed away in Vienna at the age of 92.

By the time Frankl died, his work had impacted millions worldwide. He is the author of 39 books, and in the 76 years since he first published Man’s Search for Meaning, the book has been translated into more than 50 languages and sold over 16 million copies. His insights into finding purpose under the most horrific conditions deeply resonated with general readers and professionals alike. Frankl’s legacy endures through his contributions to psychotherapy and other disciplines, as well as through his message of resilience, hope, and the importance of meaning in life.

Some of the quotes that Viktor Frankl is known for include:

Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s way.

When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.

Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how’.

An abnormal reaction to an abnormal situation is normal behavior.

No man should judge unless he asks himself in absolute honesty whether in a similar situation he might not have done the same.

What is to give light must endure burning.

For the first time in my life, I saw the truth as it is set into song by so many poets, and proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers. The truth — that Love is the ultimate and highest goal to which man can aspire. Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of man is through love and in love.

Life is never made unbearable by circumstances, but only by lack of meaning and purpose.

Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.

Forces beyond your control can take away everything you possess except one thing, your freedom to choose how you will respond to the situation.

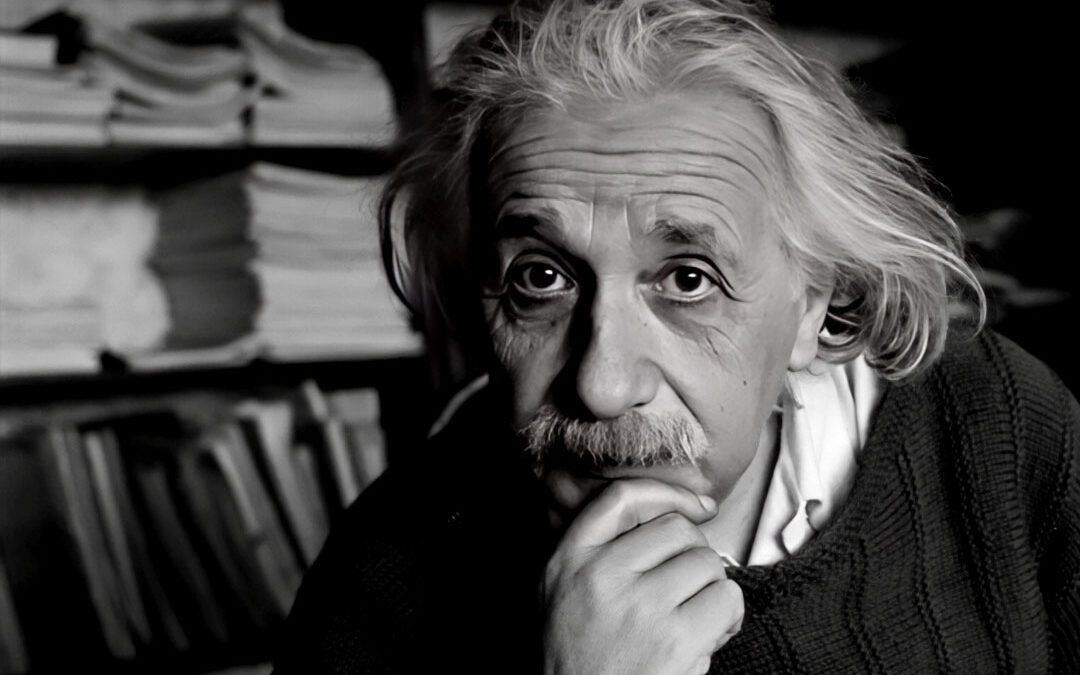

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of theoretical physicist Albert Einstein, one of the most influential scientists in human history. He is best known for developing the theory of relativity and won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1921. His mass-energy equivalence formula E=mc² is considered the most famous scientific equation in the world, and he was a dedicated champion for peace.

Albert Einstein was born in 1879 in Ulm, in the Kingdom of Württemberg in the German Empire. His parents were secular Ashkenazi Jews. Einstein‘s father was a salesman and engineer, who ran a business that manufactured electrical equipment. His mother was a well-educated woman who played a significant role in her son’s early education, particularly in music. She was a talented pianist, and her influence is thought to have contributed to Einstein’s lifelong love of music.

Shortly after Einstein’s birth, his family moved to Munich, where his father and uncle co-founded an electrical engineering company. During his early years, Einstein’s parents noticed his slow development, particularly his delayed speech, which caused them some concern. Despite this, he exhibited a strong curiosity and interest in the world around him, often spending long periods pondering simple objects. The family environment was intellectually stimulating, with his mother nurturing his interest in music, particularly the violin, and his father exposing him to scientific ideas.

In 1884, at the age of five, Einstein had a pivotal experience with a compass, which deepened his fascination with invisible forces and sparked his lifelong interest in understanding the mysteries of the natural world. In 1885, at the age of six, he began taking violin lessons, and he became a passionate violinist who played the instrument throughout most of his life.

In 1888, Einstein started attending the Luitpold Gymnasium in Munich, where he was an excellent student, although his personality often clashed with the rigid, rote-learning educational system. Einstein’s independent spirit and curiosity often put him at odds with the school’s strict approach, but he found solace in self-study, particularly in mathematics, which he pursued with great enthusiasm. In 1891, at the age of 12, Einstein began teaching himself advanced mathematics, including calculus, which fueled his fascination with physics.

During this period, his family’s business began to struggle, leading to financial difficulties. In 1894, when Einstein was 15, his family moved to Italy for better business opportunities, but he stayed behind to finish school. However, unhappy with the schooling system, Einstein eventually left the Luitpold Gymnasium and joined his family in Italy.

That same year Einstein applied to the Swiss Federal Polytechnic in Zurich. Although he initially failed the entrance exam in 1895, he was accepted after completing additional schooling in Aarau, Switzerland. In 1896, Einstein renounced his German citizenship to avoid military service and became stateless. He then enrolled at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic, where he studied under renowned physicists and developed his foundational ideas in theoretical physics. By 1901, Einstein graduated with a teaching diploma, became a Swiss citizen, and he published his first scientific paper.

In 1902, Einstein began working at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern, a job that provided him with financial stability and ample time to pursue his scientific interests. In 1905, Einstein published four groundbreaking papers that fundamentally changed the understanding of physics. These papers introduced the theory of special relativity, the photoelectric effect, Brownian motion, and the equivalence of mass and energy (E=mc²), establishing him as a leading physicist.

Einstein’s theory of special relativity states that the laws of physics are the same for all observers, regardless of their constant speed, and that the speed of light is constant in a vacuum. This understanding leads to unusual phenomena like time dilation and length contraction when objects move close to the speed of light.

In 1909, Einstein left the patent office to accept a full-time academic position at the University of Zurich, marking the beginning of his academic career. In 1912, Einstein moved to Prague to take up a professorship and then returned to Zurich, where he continued to develop his theories, including the early stages of his work on general relativity.

In 1913, Einstein accepted a position at the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin, where he also became the director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics. During World War I, despite the turbulent times, Einstein continued his work on the theory of general relativity, which he completed in 1915.

General relativity expanded his concept of special relativity by describing gravity not as a force, but as a curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy. Massive objects cause spacetime to curve, and this curvature affects the motion of objects and the flow of time. This theory revolutionized the understanding of gravity and was experimentally confirmed in 1919 during a solar eclipse, which brought Einstein global fame.

The 1920s saw Einstein become a prominent public figure, traveling extensively and promoting his scientific ideas. In 1921, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his explanation of the photoelectric effect, which was crucial in the development of quantum theory. Throughout this period, Einstein also engaged in various humanitarian and political causes, advocating for peace and Zionism. During the end of this decade, Einstein focused on unifying the fundamental forces of physics, although he grew increasingly skeptical of the emerging field of quantum mechanics. In the early 1930s, as the political situation in Germany deteriorated with the rise of the Nazi regime, he decided to leave Germany.

In 1933, when Einstein was fleeing Germany to the United States, he stopped in England, where he stayed with the famous author H.G. Wells. During this visit, Einstein met Charlie Chaplin at the premiere of the film City Lights. Chaplin reportedly said, “They cheer me because they all understand me, and they cheer you because no one understands you,” to which Einstein smiled in agreement.

That same year Einstein settled in the United States, accepting a position at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he would remain for the rest of his life. During this time, Einstein became an outspoken advocate against fascism and war, supporting efforts to help Jewish refugees. He also played a role in alerting President Franklin D. Roosevelt to the potential of nuclear weapons, contributing to the initiation of the Manhattan Project, although he was a lifelong pacifist.

In 1940, Einstein became an American citizen, fully committed to both his scientific pursuits and his advocacy for global peace and human rights. After the war, Einstein became a vocal advocate for nuclear disarmament, warning about the dangers of atomic weapons and promoting peaceful uses of atomic energy. He was an outspoken supporter of civil rights and was affiliated with various humanitarian causes. Einstein became a symbol of intellectual freedom and moral integrity, and in 1952 he rejected an offer to become the president of Israel, choosing instead to focus on science and advocacy.

Einstein’s views on spirituality were complex and nuanced. He did not believe in a personal God or traditional religious doctrines, but he often spoke of a “cosmic religion” or “cosmic sense” that reflected a deep reverence for the order and mystery of the universe. He saw spirituality in the awe and wonder inspired by nature and the intricate laws governing the cosmos, famously saying, “God does not play dice with the universe.” Einstein’s spirituality was rooted in his belief in a rational, comprehensible universe, which he felt revealed a higher order or intelligence, though not one tied to human-like deities or religious dogma.

Despite declining health in his final years, Einstein remained active in his research and public life. He also continued to work on his Unified Field Theory, although it remained incomplete at the time of his death. Einstein died in 1955 at the age of 76, leaving behind a legacy that profoundly shaped both the scientific world and broader society.

Einstein’s theories revolutionized our understanding of space and time, and he was a passionate advocate for peace, civil rights, and humanitarian causes, using his fame to influence global affairs. His contributions continue to shape modern physics, and his image remains synonymous with creativity, curiosity, and the pursuit of knowledge.

Some of the quotes that Albert Einstein is known for include:

Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.

Two things are infinite: the universe and human stupidity; and I’m not sure about the universe.

There are only two ways to live your life. One is as though nothing is a miracle. The other is as though everything is a miracle.

I am enough of an artist to draw freely upon my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.

Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance, you must keep moving.

If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.

Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one.

The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion that stands at the cradle of true art and true science.

If I were not a physicist, I would probably be a musician. I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music.

Great spirits have always encountered violent opposition from mediocre minds.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of British primatologist and anthropologist Jane Goodall, who studied the social interactions of chimpanzees in the wild for over sixty years and is considered the world’s foremost expert. She has also been an important voice for wildlife conservation and animal welfare issues.

Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall was born in London, England in 1934. Her father was a successful racing car driver and a businessman in the automobile industry. Her mother was a novelist. As a child, Goodall’s father gave her a stuffed toy chimpanzee named Jubilee as an alternative to a teddy bear, and Goodall has said that her fondness for the special toy sparked her early love of animals. To this day, Jubilee sits on Goodall’s dresser in her home.

Goodall attended Uplands School, a private school located in the coastal town of Poole, Dorset on the south coast of England, Goodall did not pursue higher education immediately after school; instead, she worked as a secretary and saved money for a trip to Africa. In 1957, Goodall visited the farm of a friend in the Kenya highlands of East Africa. This visit brought her into contact with the renowned anthropologist and paleontologist Louis Leakey. Impressed by Goodall’s passion for animals and her keen observational skills, Leakey hired her as his secretary and soon after, recognized her potential to contribute to primate research.

In 1960, Leakey sent Goodall to Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania to study wild chimpanzees, marking the beginning of her groundbreaking research. Despite having no formal training in higher education at the time, Goodall’s intuitive and patient approach led to remarkable discoveries about chimpanzee behavior, tool use, and social structures, which revolutionized our understanding of the primates and their close relation to humans. She found that “it isn’t only human beings who have personality, who are capable of rational thought and emotions like joy and sorrow.”

In the early 1960s, while Goodall was still new to studying chimpanzees in Gombe Stream National Park, she faced a significant challenge: the chimpanzees were very wary of her presence and they would flee whenever she approached. To overcome this, Jane adopted a unique and patient strategy. She would sit quietly in the same spot every day, making sure not to intrude or disrupt the chimpanzees’ activities. Her perseverance paid off when a young chimpanzee that she named “David Greybeard” became the first to approach her.

David’s acceptance of Goodall paved the way for other chimpanzees to become more comfortable around her. This breakthrough was not only a pivotal moment in her research but also led to the groundbreaking discovery of tool use among chimpanzees, fundamentally changing our understanding of primate behavior and bridging the gap between humans and animals in the scientific community. David’s trust in Goodall marked the beginning of her long and fruitful relationship with the chimpanzees of Gombe, and it remains a testament to the power of patience and respect in scientific observation.

In 1962, Goodall began her higher education at the University of Cambridge, where she enrolled in a Ph.D. program despite not having an undergraduate degree, which was a rare exception. In 1965, Goodall obtained her Ph.D. in Ethology from Darwin College, Cambridge. Her thesis was titled Behavior of the Free-Ranging Chimpanzee, based on her pioneering field research in Gombe.

Goodall was able to correct quite a few misunderstandings that people had about chimpanzees. For example, she discovered that they are omnivorous, and not vegetarian as was previously thought. Goodall learned that they are capable of making and using tools, and have a set of previously unrecognized complex and highly developed social behaviors. She summarized her findings in several books and articles about various aspects of her work.

Goodall is the author 36 books. In 1971, she published her book In the Shadow of Man, which is her initial account of her life among the wild chimpanzees of Gombe, and in 1986, she summarized her years of observation in The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior. Some of her other varied books include A Prayer for World Peace and Reason for Hope: A Spiritual Journey. She also wrote a cookbook, Eat Meatless, and a children’s book, Pangolina.

Goodall’s work and life have been deeply intertwined with spirituality, although she does not adhere to a specific organized religion. Goodall’s spirituality is rooted in a profound sense of connection to nature and all living beings, which she often describes in her writings and speeches. Her spiritual perspective is reflected in her reverence for the natural world and her commitment to conservation and animal welfare. Goodall often speaks about the sense of awe and wonder she feels in the presence of nature, and how this has guided her work with chimpanzees and her broader environmental advocacy. Her spirituality also informs her belief in the power of hope and the potential for positive change through human action.

In 1975, while Goodall was studying the wild chimps in Gombe, along with several of her research students and assistants, a harrowing incident occurred when several of them were kidnapped by armed rebels in Tanzania. The rebels, from the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo (then Zaire), crossed into Tanzania and took the students hostage. The incident was a significant and frightening disruption to Goodall’s research. The students were held captive for several hours, but fortunately, they were released unharmed after negotiations. This event underscored the challenges and dangers faced by researchers working in remote and politically unstable regions. Despite this traumatic experience, Goodall continued her work at Gombe, demonstrating her resilience and dedication to her research and conservation efforts.

In 1977, the Jane Goodall Institute was founded, which is dedicated to wildlife research, conservation, and education. Its primary focus is on the protection of chimpanzees and their habitats, promoting sustainable livelihoods for local communities, and fostering environmental stewardship through programs that engage young people worldwide in conservation efforts. The institute also works on issues such as reforestation, climate change, and advocacy for animal welfare and biodiversity.

In 1991, Goodall started her Roots & Shoots program. This is a global youth-led community action program that encourages young people to make a positive impact in their communities through projects that promote conservation, animal welfare, and social justice. The program empowers participants to identify and address local issues, fostering leadership skills and environmental stewardship. Through various initiatives, Roots & Shoots “aims to inspire and support the next generation of compassionate leaders committed to creating a better world for people, animals, and the environment.” The program has had an incredible impact and has grown exponentially since its inception, engaging millions of young people in over 100 countries in community-based conservation projects.

Goodall has continued to make significant contributions to primatology, conservation, and environmental advocacy. In 1993, she founded the Tchimpounga Chimpanzee Rehabilitation Center in the Republic of Congo, providing a sanctuary for orphaned chimpanzees and raising awareness about the threats they face. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, Goodall expanded her efforts globally through the Jane Goodall Institute, promoting sustainable development and conservation initiatives in Africa and elsewhere.

Goodall has lectured widely about environmental and conservation issues and is the recipient of numerous awards and honors. In 1995, she won the Kyoto Prize, and in 2002 she became a United Nations Messenger of Peace. In 2003, Goodall was honored as the Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire. In 2021, she also was awarded the Templeton Prize, and in 2022 she won the Stephen Hawking Medal for Science Communication. In 2006, the Open University of Tanzania awarded her an honorary Doctor of Science degree, and in 2017, a documentary about Goodall’s life and work titled Jane was released by National Geographic.

Goodall has been a tireless advocate for animal welfare and environmental protection, delivering lectures worldwide and meeting with global leaders to discuss these critical issues. Goodall’s unwavering dedication has inspired a global movement towards a more sustainable and compassionate world. I met Jane in 1993 at the opening celebration for the Biosphere 2 project in Arizona, which was the largest closed ecological system ever created. She was extremely kind and gracious as we spoke, and I could sense why animals feel so comfortable and trusting around her beautiful presence.

Some of the quotes that Jane Goodall is known for include:

What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make. The greatest danger to our future is apathy. You cannot get through a single day without having an impact on the world around you.

We have the choice to use the gift of our life to make the world a better place– or not to bother.

You cannot share your life with a dog, as I had done in Bournemouth, or a cat, and not know perfectly well that animals have personalities and minds and feelings.

From my perspective, I absolutely believe in a greater spiritual power, far greater than I am, from which I have derived strength in moments of sadness or fear. That’s what I believe, and it was very, very strong in the forest.

If we do not do something to help these creatures, we make a mockery of the whole concept of justice.

Only if we understand, will we care. Only if we care, will we help. Only if we help shall all be saved.

Here we are, the most clever species ever to have lived. So how is it that we can destroy the only planet we have?

Giving people hope is my mission in life.

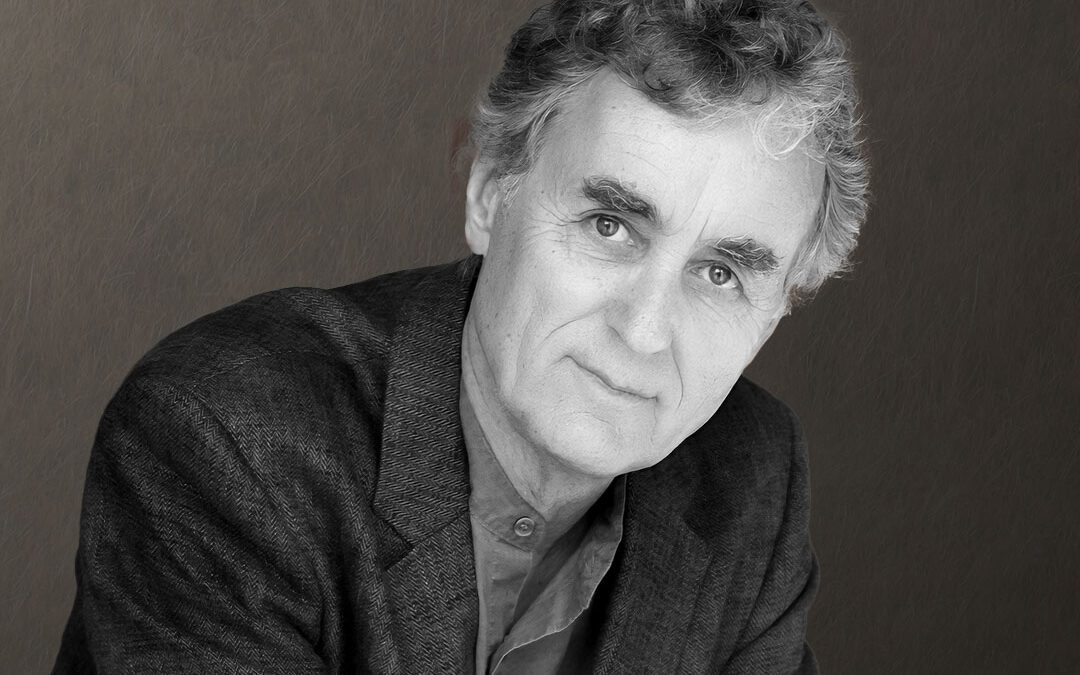

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of physicist, activist, and ecologist Fritjof Capra, who is the founding director of the Center for Ecoliteracy, and author of several bestselling books, including The Tao of Physics, which explores the relationship between Eastern philosophy and modern physics.

Fritjof Capra was born in Vienna, Austria in 1939. His father was an attorney and his mother was a poet. Capra attended the University of Vienna and earned his Ph.D. in theoretical physics in 1966. Capra also studied numerous languages and is fluent in German, English, Italian, and French.

Capra conducted physics research at several prestigious institutions. Between 1966 and 1968, he was a researcher at the University of Paris. Between 1968 and 1970, he conducted research at the University of California, Santa Cruz. In 1970, he was a researcher at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center in Palo Alto, California, and then at Imperial College in London between 1971 and 1974. Between 1975 and 1988, Capra worked at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory in Northern California.

Capra was involved in theoretical high-energy physics research, focusing on quantum field theory and particle physics. He worked on topics related to the physics of subatomic particles, exploring the fundamental forces and interactions that govern their behavior. Capra’s work included studying the properties and interactions of elementary particles, contributing to the understanding of quantum mechanics, and developing theoretical frameworks that describe particle interactions.

In 1975, while Capra was a researcher in Northern California, he joined the Fundamental Fysiks Group, which met weekly to discuss philosophy and quantum physics. Our friend Nick Herbert, who I wrote a profile about a while back, was also a member of this legendary group that revolutionized physics. David Kaiser’s book How the Hippies Saved Physics, chronicles how this group of unconventional physicists in the 1970s, blended psychedelic and counterculture influences with scientific inquiry, to help revive interest in the foundations of quantum mechanics and contribute to the development of quantum information science.

That same year Capra published his groundbreaking book The Tao of Physics, which became a bestseller and was translated into twenty-three languages. The book explores the parallels between modern physics and Eastern mysticism, suggesting that both realms offer complementary perspectives on the nature of reality. Capra argues that quantum mechanics and relativity discoveries reflect the holistic and interconnected worldview found in ancient spiritual traditions such as Taoism, Buddhism, and Hinduism.

In 1982, Capra published his book The Turning Point, which examines the failures of modern society’s mechanistic worldview and advocates for a paradigm shift towards a more holistic, ecological approach to science, economics, and society. In 1988, Capra published Uncommon Wisdom: Conversations with Remarkable People, a series of dialogues that he had with several brilliant thinkers, such as Alan Watts, Gregory Bateson, Krishnamurti, and R.D. Laing about the interconnectedness of life and the universe.

In 1990, the movie Mindwalk — starring Liv Ullmann, Sam Waterston, and John Heard— was released, and Capra co-wrote the screenplay. The film — which is about three people who engage in a deep philosophical discussion on a variety of topics, including science, politics, and the interconnectedness of life, while walking around the island of Mont Saint-Michel in France — is loosely based on his book, The Turning Point.

In 1991 Capra co-authored Belonging to the Universe: Explorations on the Frontiers of Science and Spirituality with a Benedictine monk David Steindl-Rast. The book explores parallels between new paradigm thinking in science and religion, and it won the American Book Award in 1992.

In 1995, Capra co-founded the Center for Ecoliteracy in Berkeley, California. The organization is dedicated to promoting ecological education in schools and integrates ecological principles into the curriculum to foster environmental awareness and sustainability among students. It has supported projects in habitat restoration, school gardens, and cooking classes, partnerships between farms and schools, school food transformation, and curricular innovation.

In 1996, Capra published his book The Web of Life, which presents a new scientific understanding of living systems, emphasizing the interconnectedness and interdependence of all life forms through the principles of complexity, networks, and ecology. In 1998, Capra received the New Dimensions Broadcaster Award, in 1999 he received the Bioneers Award, and in 2007 he was inducted into the Leonardo da Vinci Society for the Study of Thinking.

In 2002, Capra published The Hidden Connections, and he co-authored The Systems View of Life in 2014. Both books emphasize the interconnectedness and complexity of living systems, integrating perspectives from biology, ecology, and social sciences to understand the holistic nature of life. Capra has also taught physics classes at the University of California Santa Cruz, University of California, Berkeley, and San Francisco State University over the years.

In 2018, at an event hosted by our friend Ralph Abraham, I met Fritjof Capra. I told him how much I had enjoyed his book The Tao of Physics, and asked him about his inspiration for writing it. Fritjof then described to me how he was sitting on a beach in Santa Cruz when he experienced the revelations that led to his integration of physics with Taoism, and how mystical experiences that he had with “power plants” had played a role in his insight.

Some of the quotes that Fritjof Capra is known for include:

The mystic and the physicist arrive at the same conclusion; one starting from the inner realm, the other from the outer world. The harmony between their views confirms the ancient Indian wisdom that Brahman, the ultimate reality without, is identical to Atman, the reality within.

Mystics understand the roots of the Tao but not its branches; scientists understand its branches but not its roots. Science does not need mysticism and mysticism does not need science; but man needs both.

Quantum theory thus reveals a basic oneness of the universe. It shows that we cannot decompose the world into independently existing smallest units. As we penetrate into matter, nature does not show us any isolated “building blocks,” but rather appears as a complicated web of relations between the various parts of the whole. These relations always include the observer in an essential way. The human observer constitute the final link in the chain of observational processes, and the properties of any atomic object can be understood only in terms of the object’s interaction with the observer.

The more we study the major problems of our time, the more we come to realize that they cannot be understood in isolation. They are systemic problems, which means that they are interconnected and interdependent.

At the deepest level of ecological awareness you are talking about spiritual awareness. Spiritual awareness is an understanding of being imbedded in a larger whole, a cosmic whole, of belonging to the universe.

In ordinary life, we are not aware of the unity of all things, but divide the world into separate objects and events. This division is useful and necessary to cope with our everyday environment, but it is not a fundamental feature of reality. It is an abstraction devised by our discriminating and categorizing intellect. To believe that our abstract concepts of separate ‘things’ and ‘events’ are realities of nature is an illusion.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of pioneering cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead, who profoundly influenced the social sciences by studying the behavioral patterns of different cultures, particularly in the South Pacific. Mead’s groundbreaking work challenged Western perceptions of human development and sexuality, emphasizing cultural variability.

Margaret Mead was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1901. Her father was a professor of finance, her mother was a sociologist, and she had four younger siblings. As a child, Mead’s family moved around frequently, and her grandmother largely educated her.

In 1912, when Mead was eleven, she was enrolled at the Buckingham Friends School in Lahaska, Pennsylvania. In 1919, Mead studied for a year at DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana, and then she transferred to Barnard College in New York City. Mead graduated from Barnard in 1923, and then she received her master’s degree in psychology from Columbia University a year later.

In 1925, Mead set out for the Polynesian island of Tau in the South Pacific Ocean. This was where she did her first ethnographic fieldwork, studying the life of Samoan girls and women. Mead’s observations were summarized in the now-classic book Coming of Age in Samoa, published in 1928, and describe how Samoan children were raised and educated and how sexual relations occurred in the culture. Mead also studied personality development on the island, as well as dance, interpersonal conflict, and how Samoan women matured into old age.

Coming of Age in Samoa contrasts development in Samoa with that in the United States, and the book was received with wide acclaim for its revolutionary approach to understanding adolescence in different cultures. It became a bestselling work and has been highly influential in the field of anthropology. However, it wasn’t without controversy. Some conservative groups and individuals were uneasy with the book’s conclusions, which contradicted traditional views on adolescence and morality.

In 1926, Mead was back in New York City, where she became an assistant curator at the American Museum of Natural History, and in 1929 she received her Ph.D. in anthropology from Columbia University.

In 1929, Mead visited the island of Manus, which is now part of Papua New Guinea, where she did more cultural studies. In 1930, Mead published her book Growing Up in New Guinea, which is about her encounters with the indigenous people of the Manus— before they had been changed by missionaries and other Western influences— and she compares their views on family, marriage, sex, child-rearing, and religious beliefs to those of westerners. As with her pioneering studies in Samoa, Mead’s studies in New Guinea also challenged prevailing Western views on adolescence, gender roles, and cultural norms.

In 1932, Mead met anthropologist Gregory Bateson while conducting anthropological fieldwork on the shores of the Sepik River in New Guinea, and they married in 1936. That same year, the couple traveled to Bali, Indonesia, where they helped to pioneer Visual Anthropology, a subfield of anthropology that uses visual media— such as film, photography, and digital imagery— to study and communicate cultural practices and social phenomena. Mead and Bateson were some of the earliest anthropologists to emphasize the importance of photography as a tool for ethnographic research, and they used visual media extensively during their fieldwork to capture cultural practices and everyday life. They believed that visual records provided invaluable data and insights that complemented written ethnographies.

In 1935, Mead published Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies. This is a study of the intimate lives of three New Guinea tribes from infancy to adulthood. Focusing on the “gentle, mountain-dwelling Arapesh, the fierce, cannibalistic Mundugumor, and the graceful headhunters of Tchambuli,” Mead advanced the theory that many so-called masculine and feminine characteristics are not based on biological sex differences but reflect the cultural conditioning of different societies. For example, the Tchambuli tribe exhibited a unique gender role reversal, compared to the West, in which women dominated economic and social activities while men engaged in artistic and emotionally expressive pursuits.

Mead continued to study the cultures of the Pacific islands. In 1949, she published Male and Female, an anthropological examination of seven Pacific island tribes. Mead analyzed the dynamics of these cultures, to explore the evolving meaning of “male” and “female” in contemporary American society, and the book also offers hope, by providing examples of how to resolve conflict between the sexes. When it was published The New York Times declared, Dr. Mead’s book has come to grips with the cold war between the sexes and has shown the basis of a lasting sexual peace.”

From 1946 to 1969, Mead was curator of ethnology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, where she had been an assistant curator twenty years earlier. From 1954 to 1978, Mead taught anthropology at Columbia University and The New School for Social Research in New York City. In 1960, Mead served as president of the American Anthropological Association in the 1960s and 1970s, and she held various positions in the New York Academy of Sciences and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Mead also had an interest in altered states of consciousness. She shared professional circles with, and interacted with, our friends neuroscientist John C. Lilly and psychologist Timothy Leary. Mead and Bateson contributed to conversations about the nature of human consciousness by emphasizing cultural relativity, interconnectedness, and systems thinking. In later life, Mead mentored many young anthropologists and sociologists, including psychologist Jean Houston, whom I did a profile about several months ago. In 1976, Mead was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. Mead died in 1978 at the age of 76.

In 1979, U.S. President Jimmy Carter announced he was awarding the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously to Mead. In 1984, Mead and Bateson’s daughter, anthropologist Mary Catherine Bateson, published a book, With a Daughter’s Eye, about her experience growing up with two of the world’s legendary anthropologists. In 1998, the U.S. Post Office issued a 32-cent stamp with Mead’s face.

The Margaret Mead Award is presented annually in Mead’s honor by the Society for Applied Anthropology and the American Anthropological Association, for significant works that communicate anthropology to the general public. There are schools named after Mead: a junior high school in Elk Grove Village, Illinois, an elementary school in Sammamish, Washington, and another in Brooklyn, New York.

Some of the quotes that Margaret Mead is known for include:

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed, citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.

Children must be taught how to think, not what to think.

I was wise enough never to grow up, while fooling people into believing I had.

Laughter is man’s most distinctive emotional expression.

As the traveler who has once been from home is wiser than he who has never left his own doorstep, so a knowledge of one other culture should sharpen our ability to scrutinize more steadily, to appreciate more lovingly, our own.

Always remember that you are absolutely unique. Just like everyone else.

… the ways to get insights are: to study infants; to study animals; to study primitive people; to be psychoanalyzed; to have a religious conversion and get over it; to have a psychotic episode and get over it; or to have a love affair with an old Russian…

An ideal culture is one that makes a place for every human gift.

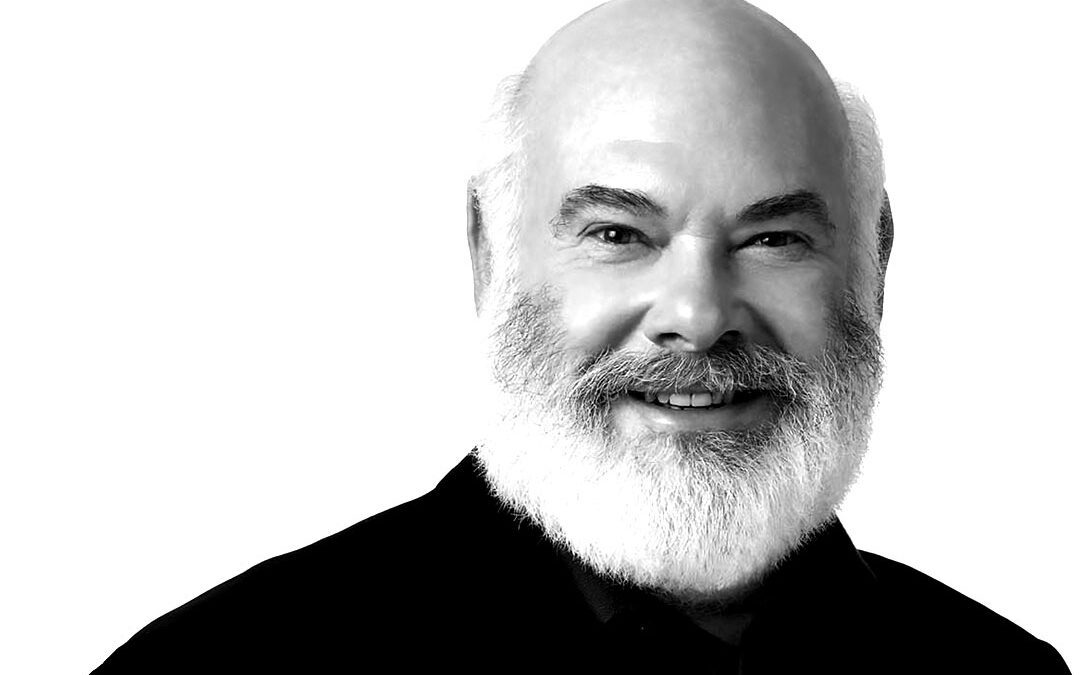

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of Andrew Weil, M.D., who is an internationally recognized expert on Integrative Medicine, which combines the best therapies of conventional and alternative medicine. Weil’s lifelong study of medicinal herbs, mind-body interactions, and alternative medicine has made him one of the world’s most trusted authorities on unconventional medical treatments, as his sensible, interdisciplinary medical perspective strikes a strong chord in many people.

Andrew Thomas Weil was born in Philadelphia in 1942, and he grew up as an only child. His parents operated a hat-making store and were Reform Jews. In 1959, Weil graduated from high school, and he was awarded a scholarship that allowed him to study abroad for a year, living with families in India, Thailand, and Greece. As a teenager, he was deeply influenced by Aldous Huxley’s book The Doors of Perception, about the author’s visionary experiences.

In 1960, Weil was admitted to Harvard University, where he studied biology, with a concentration in ethnobotany. Weil had an interest in psychoactive drugs, and while at Harvard, he met with Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (Ram Dass), and wrote about their research, as well as some of their extracurricular exploits, in a series of articles for the school paper, The Harvard Crimson, which stirred up considerable controversy.

In 1964, Weil graduated “cum laude,” and he entered Harvard Medical School, “not to become a physician but rather simply to obtain a medical education.” Weil received his medical degree in 1968 after the Harvard faculty threatened to withhold it because of a controversial cannabis study that he helped conduct in his final year.

After Weil received his medical degree, he moved to San Francisco and completed a one-year internship at Mount Zion Hospital. During this time in San Francisco from 1968 to 1969, Weil volunteered at the Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic. Weil then spent a year attending a program at the National Institute of Health, before taking a position at the National Institute of Mental Health to pursue his interest in psychoactive drugs.

In 1971, Weil experienced opposition to his line of inquiry at the National Institute of Mental Health, so he left for his home in rural Virginia, where he began to experiment with different health-enhancing practices— such as Yoga, meditation, and a vegetarian diet— and he began writing a book. In 1972, his book The Natural Mind was published, which is an investigation into the relationship between drugs and higher consciousness, and has sold over 10 million copies to date.

From 1971 to 1984, Weil was on the research staff of the Harvard Botanical Museum, where he conducted investigations into medicinal and psychoactive plants. Then from 1971 to 1975, as a Fellow of the Institute of Current World Affairs, Weil traveled throughout Central and South America, collecting information and specimens for this research. These explorations— where he not only studied plants but indigenous peoples, their medicine, and pharmacology—were to have a profound effect on Weil’s medical career.

In 1994, Weil founded the Arizona Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine in Tucson, where he serves as director to this day. Weil is also the founder of True Food Kitchen, a restaurant chain serving meals on the premise that “food should make you feel better.” There are currently 44 restaurants in this chain.

Weil has had a life-long talent for blending the conventional with the unconventional, and he has been interested in altered states of consciousness, and how the mind affects health, since before he began studying medicine. He has written extensively about this interest, and about how his early psychedelic experiences profoundly influenced his views on medicine. Because of this interest in altered states of consciousness, Weil has been honored by having a psychedelic mushroom named after him— Psilocybe Weilii— which was discovered in 1995.

Weil is the author of more than twenty popular books, including The Marriage of the Sun and Moon, From Chocolate to Morphine, Natural Medicine, Spontaneous Healing, and Healthy Aging. In addition to being the Director of the Program in Integrative Medicine at the University of Arizona’s College of Medicine, Weil also holds appointments as a Clinical Professor of Medicine, Professor of Public Health, and the Lovell-Jones Professor of Integrative Rheumatology.

Weil has been a frequent guest on many television shows, such as Larry King Live, Oprah, and The Today Show. He has also appeared in three videos featured on PBS: Spontaneous Healing, Eight Weeks to Optimum Health, and Healthy Aging. Many of his books are New York Times bestsellers, and he has appeared on the cover of Time magazine twice, in 1997 and again in 2005. USA Today” said, “Clearly, Dr. Weil has hit a medical nerve,” and The New York Times Magazine said, “Dr. Weil has arguably become America’s best-known doctor.”

I interviewed Andrew Weil in 2006. We talked about some of the most important lessons that physicians aren’t being taught in medical school, why conventional Western medicine needs to be more open-minded about alternative medical treatments, and how the mind and spirituality affect health. This interview appears in my book Mavericks of Medicine. Here is an excerpt from our conversation:

David: What role do you see the mind and consciousness playing in the health of the body?

Andrew Weil: I think it’s huge. This is an area that I’ve been interested in, I think, since I was a teenager— long before I went to medical school— and a lot of my early work was with altered states of consciousness and psychoactive drugs. I reported a lot of things that I saw about how physiology changed drastically with changes in consciousness. I just reviewed a paper from Japan; one of the authors is a doctor I know. This is a group of people looking at how emotional states affect the genome. They have shown, for example, that laughter can affect gene expression in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Now that’s really interesting stuff, and I think that this is the type of research that is generally not looked at here. I think that our mental states— our states of consciousness— have a profound influence on our bodies, and even our genes. And I think they have a lot to do with how we age.

David: What role do you think that spirituality plays in health?

Andrew Weil: Again, I think, large, but it’s hard to define spirituality. For me, I make a very sharp distinction between spirituality and religion. Religion is really about institutions, and for me, spirituality is about the nonphysical, and how to access that and incorporate it into life. In “Eight Weeks to Optimum Health,” I gave a lot of suggestions each week about things that people can do to improve or raise spiritual energy, and they are things that at first many people might not associate with spirituality. But they were recommendations like having fresh flowers in your living space and listening to pieces of music that elevate your mood. Some of the other suggestions included spending more time with people in whose company you feel more optimistic and better, and spending time in nature. I think that I would put all of these in the realm of spiritual health.