Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

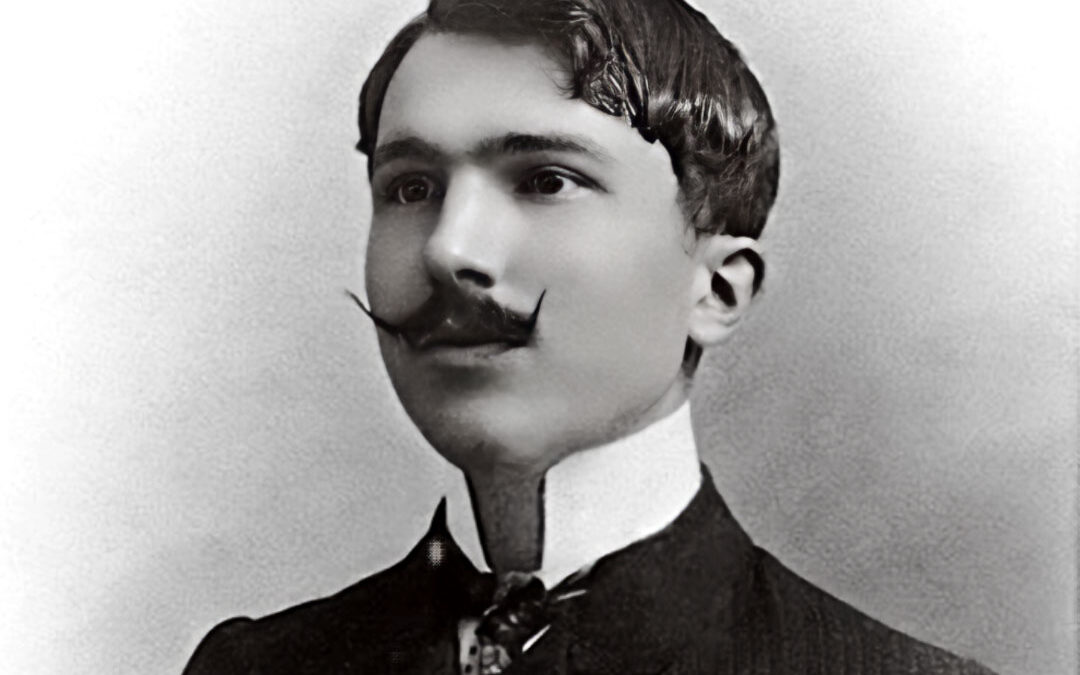

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky was born in Moscow, Russia, in 1821. He had an older brother, his father was a doctor, and he was raised in his family’s home, which was on the grounds of the Mariinsky Hospital for the Poor. This hospital was in a lower-class district on the edges of Moscow, and when playing in the hospital gardens as a child Dostoevsky encountered patients who were at the bottom of the Russian social scale.

When Dostoyevsky was four years old his mother used the Bible to teach him how to read and write, and he was introduced to books at an early age. His nanny read him fairy tales, legends, and heroic sagas, and his parents introduced him to a wide range of literature. Although his father’s approach to education has been described as “strict and harsh,” Dostoevsky reported that his “imagination” was “brought alive” by his parent’s nightly readings.

In 1837 Dostoyevsky left school to enter the Nikolayev Military Engineering Institute, and after graduating he worked as a lieutenant engineer and book translator, from French into Russian. In 1839 signs of Dostoevsky’s epilepsy first appeared, and his seizures plagued him throughout his life. During his 20s, Dostoyevsky recorded several journal descriptions of his seizures, and there are also descriptions in his novels. There have been numerous medical hypotheses about the type of epilepsy with which Dostoevsky suffered, the most notorious feature of his type of epilepsy being the so-called “ecstatic aura.” While these seizures were debilitating, they also appear to have contributed to mystical experiences that enhanced the creativity of his writing.

Dostoyevsky had this to say about his epileptic seizures, “I felt that heaven descended to earth and swallowed me. I attained God and was imbued with him… all the joys life can give I would not take in exchange for it… for a few moments before the fit, I experience a feeling of happiness such [that] it is impossible to imagine in a normal state and which other people have no idea of. I feel entirely in harmony with myself and the world, and this feeling is so strong and so delightful that for a few seconds of such bliss, one would gladly give up ten years of one’s life if not one’s whole life.”

Between 1844 and 1845 Dostoyevsky wrote his first novel, Poor Folk. His motivation for writing this novel was said to be largely financial. Dostoyevsky was having financial difficulties, due to an extravagant lifestyle and a gambling addiction, so he decided to write a novel to try and raise funds. The novel is written in the form of letters between the two main characters, who are poor relatives, and it describes the lives of poor people, their relationship with rich people, and poverty in general. This novel became a commercial success, and it gained Dostoyevsky’s entry into Saint Petersburg’s literary circles.

In 1846 Dostoyevsky’s second novel, The Double: A Petersburg Poem, about a bureaucrat struggling to succeed, was published in a journal and it received negative reviews. Around this time Dostoyevsky also published several short stories in a magazine, which also received negative reviews, and this caused him stress and greater financial difficulty. After this his health declined, his seizures increased in frequency, and Dostoyevsky’s life took a dark turn.

In 1847 Dostoyevsky was arrested for belonging to a particular literary group called the Petrashevsky Circle, which discussed banned books that were critical of Tsarist Russia. Dostoyevsky was sentenced to death, but at the last moment, his sentence was commuted. He later described this experience, of what he believed to be the last moments of his life, in his novel The Idiot. Dostoyevsky spent the next four years doing hard labor in a Siberian prison camp, where he had frequent seizures, and then after surviving that, he had to do six more years of compulsory military service.

In the years that followed Dostoyevsky worked as a journalist, editing several magazines, and he traveled around Western Europe. For a time, he experienced such serious financial hardship that he had to beg for money. In 1866, when he owed large sums of money to creditors, his widely acclaimed novel Crime and Punishment was first published in a literary journal, in twelve monthly installments. It was a “literary sensation” of 1866 and is now one of the most widely read books of all time.

The novel is about the mental anguish and moral dilemmas of an impoverished young man who plans to kill an unscrupulous old woman, who stores money and valuable objects in her apartment. What’s so remarkable about this story is how Dostoyevsky portrays the psychological process of his self-tormented main character.

Between 1868 and 1869 Dostoyevsky’s novel The Idiot was first published serially in a journal. The title of the book is an ironic reference to the central character of the novel, a young, Christ-like, epileptic prince whose “goodness, open-hearted simplicity, and guilelessness lead many of the more worldly characters he encounters to mistakenly assume that he lacks intelligence and insight.”

In 1880 Dostoyevsky published his final novel, The Brothers Karamazov, a passionate and philosophical story about rival love affairs, that explores questions of God, free will, and morality. Dostoevsky’s body of work consists of thirteen novels, three novellas, seventeen short stories, 221 Diary articles, and numerous other works.

Dostoyevsky died in 1881. Since his death, he has become one of the most widely-read and highly-regarded Russian writers. Dostoyevsky’s books have been translated into more than 170 languages, they’ve served as the inspiration for numerous films, and his work has influenced many other writers.

In 1971, Dostoevsky’s former apartment in Saint Petersburg was opened as a museum, known as the F.M. Dostoevsky Memorial Museum. The apartment was Dostoevsky’s home during the composition of some of his most notable works, including The Double: A Petersburg Poem and The Brothers Karamazov. The museum library holds around 24,000 volumes and a small collection of manuscripts.

Some quotes that Fyodor Dostoyevsky is remembered for include:

To love someone means to see them as God intended them.

Beauty will save the world.

What is hell? I maintain that it is the suffering of being unable to love.

I say let the world go to hell, but I should always have my tea.

It takes something more than intelligence to act intelligently.

Above all, don’t lie to yourself. The man who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to a point that he cannot distinguish the truth within him, or around him, and so loses all respect for himself and for others. And having no respect he ceases to love.

Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart. The really great men must, I think, have great sadness on earth.

Don’t let us forget that the causes of human actions are usually immeasurably more complex and varied than our subsequent explanations of them.

The mystery of human existence lies not in just staying alive, but in finding something to live for.

Upon Carolyn’s recommendation, I recently watched the 1964 film Zorba the Greek, which I greatly enjoyed. The movie was based on the novel by Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis, who Carolyn has raved about for years. Kazantzakis has written many other critically acclaimed works of fiction and nonfiction and is remembered today as one of Greece’s greatest writers.

Nikos Kazantzakis was born in 1883 in Heraklion, the capital city of Crete, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire. Kazantzakis was the eldest of four children. His father was a farmer and animal feed dealer, who was described as “unsociable,” while his mother was described as “saintly.”

From 1902 to 1906 Kazantzakis studied law at the University of Athens and he graduated with honors. In 1907 he went to the Sorbonne in Paris to study philosophy. In Paris, he was deeply influenced by the philosophy of Henri Bergson and the idea that “a true understanding of the world comes from the combination of intuition, personal experience, and rational thought.” Kazantzakis’ 1909 doctoral dissertation at the Sorbonne was on the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, and upon returning to Greece he began translating works of philosophy.

In 1906 Kazantzakis published his first work, an essay titled The Disease of the Century, which was published by Picture Gallery Magazine. That same year Kazantzakis also published his first book, The Serpent and Lily. Both the essay and the book were written under the pen name “Karma Nirvami,” which was one of the pseudonyms that Kazantzakis used during the first few years of his writing. His first play, Daybreak, was staged several months later at the Athenian Theater in Athens, and in 1909 he wrote a one-act play about existential themes called The Comedy.

Through the next several decades Kazantzakis traveled extensively throughout the world. He traveled around Greece and much of Europe— including Germany, Italy, France, The Netherlands, and Romania— as well as northern Africa, Egypt, Russia, Japan, and China. These travels put Kazantzakis in contact with different philosophies, ideologies, and lifestyles that would later influence his writing, as he often used his experiences to create vivid settings and characters in his works.

In 1919, Kazantzakis was appointed as the director general of the Greek Ministry of Public Welfare, although he only held this post for a year before resigning. However, during his service, he helped to feed and rescue over 150,000 Greek war victims.

In 1924 Kazantzakis first met Eleni Samiou, who was 21 years old at the time, and who devoted her life to helping Kazantzakis with his work. They began a romantic relationship around four years later, although they weren’t formally married until 1945. Samiou helped Kazantzakis by typing his drafts, commenting on his drafts before they were published, accompanying him on his travels, and managing his business affairs. They were married until his death.

In 1924 Kazantzakis also began working on an epic poem that was based on Homer’s “Odyssey,” which he retold from a contemporary perspective. Kazantzakis considered this to be his most important work. After fourteen years of writing and revision, it was finally published in 1938 as The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel.

Kazantzakis also wrote several books about his own interpretation of Christianity and Greek Orthodoxy, such as “The Saviors of God,” a series of spiritual exercises that he wrote between 1922 and 1923 and was first published in 1927. “The Saviors of God” is today widely considered to be his greatest work of philosophy. It incorporates elements from Bergson, Marx, and Nietzsche, as well as Christianity and Buddhism.

Facing financial difficulty in 1934, to earn money Kazantzakis wrote three textbooks for the second and third grades. The Greek Ministry of Education adopted one of them and his financial concerns were alleviated for a time.

In the following years, Kazantzakis wrote some of his most acclaimed works, which established him as a major Modern Greek writer. In 1946 his most famous novel, Zorba the Greek, was published. The novel beautifully contrasts the sensual and intellectual facets of human nature. It is a transformative story of a young writer who ventures off to escape his bookish, intellectual life, with the unexpected aid of a charismatic and boisterous, passionate, and mysterious peasant and musician named Alexis Zorba. The novel was adapted into the wonderful 1964 film starring Anthony Quinn that I mentioned earlier, and it won three Academy Awards.

Kazantzakis was spiritually inclined, but he had some issues with his Greek Orthodox Christian faith. As a child, he was baptized within the Greek Orthodox tradition, and he was drawn to the stories of saints. Many scholars and critics say that his works center on a search for spiritual and religious truth. Kazantzakis was exposed to different religious belief systems, like Buddhism, during his travels, influencing him to doubt his Christian faith. Although he never denied it, his criticism of Christianity caused tension within the Greek Orthodox Church and with his critics. In 1948 Kazantzakis wrote The Last Temptation of Christ and Christ Recrucified, his most controversial works, which are about questioning Christian values. The Last Temptation of Christ was condemned by the Catholic Church and was not published until 1956.

Kazantzakis’s novel Report to Greco was written in 1945, but not published until 1961. It’s an autobiographical work, and it explores Kazantzakis’s spiritual quest and his search for what he called a “new man.” In 1949 he wrote The Greek Passion, a play set during the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-22. Kazantzakis traveled extensively throughout this period, spending time in France, Austria, Italy, Germany, and the United States.

In 1953 Kazantzakis published The Greek Passion, which is a novel about a village’s struggle to cope with the Greek Civil War. Kazantzakis was also a prolific translator, translating works by Dante, Shakespeare, and many other writers into the Modern Greek language. He translated a number of notable works including The Divine Comedy, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, On the Origin of Species, and Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey.

In addition to his widely acclaimed novels, memoirs, philosophical essays, and translations, Kazantzakis also wrote travel books and he lectured widely. Kazantzakis was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature for nine different years but never won. In 1957 he lost the Prize to Albert Camus by a single vote. Camus later said that Kazantzakis deserved the honor “a hundred times more” than himself.

Kazantzakis died in 1957, in Germany, after a return flight from Asia. He is buried in Crete, at the highest point of the Walls of Heraklion, the Martinengo Bastion, which looks out over the mountains and the Sea of Crete. Kazantzakis’ epitaph reads: “I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free.”

In 1968 Eleni Samiou published a biography of her husband— Nikos Kazantzakis— The Uncompromising — which contains the story of Nikos’ life and a large number of their letters.

In 2007 a euro collectors’ coin, the €10 Euro Greek Nikos Kazantzakis commemorative coin, was minted for the 50th anniversary of his death. His image is on the obverse of the coin, while the reverse carries the National Emblem of Greece with his signature. In 2017, on the 60th anniversary of his death, the €2 Euro Greece Grecia with his image was also minted.

In 2022, 65 years after the death of Kazantzakis, fans of his work rejoiced, when his final novel Aniforos was first published. The manuscript had been kept at the Nikos Kazantzakis Museum in the author’s home village of Mirtia, Crete since its rediscovery. Aniforos was written right after Zorba the Greek in 1946, and is filled with autobiographical references and reflections on his firsthand experience of World War II.

Some of the quotes that Nikos Kazantzakis is known for include:

God changes his appearance every second. Blessed is the man who can recognize him in all his disguises.

The only thing I know is this: I am full of wounds and still standing on my feet.

A man needs a little madness, or else… he never dares cut the rope and be free.

You can knock on a deaf man’s door forever.

Since we cannot change reality, let us change the eyes which see reality.

I said to the almond tree, ‘Sister, speak to me of God.’ And the almond tree blossomed.

You have your brush, you have your colors, you paint the paradise, then in you go.

Once, I saw a bee drown in honey, and I understood.

When I first met Carolyn in the early 1980s, one of the writers that we passionately discussed was British novelist and poet D.H. Lawrence. We had both enjoyed his novels and been inspired by his sensual writings.

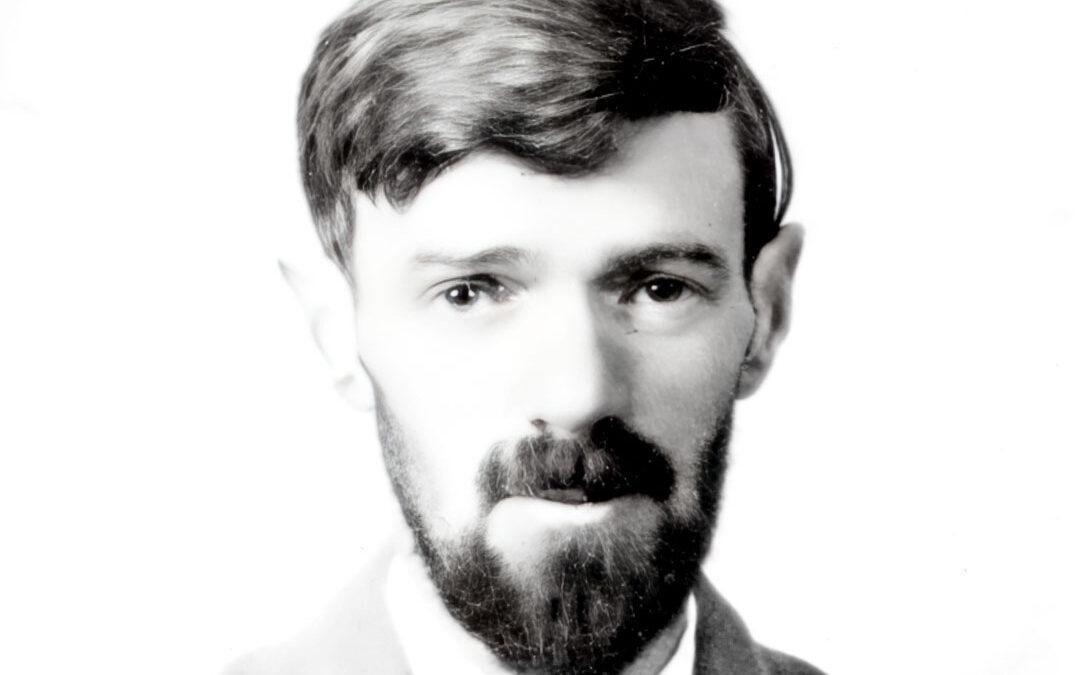

David Herbert Lawrence was born in 1885 in Eastwood, Nottinghamshire, England. His father was a barely literate coal miner and his mother was a schoolteacher. Nottinghamshire was a coal-mining town, and Lawrence’s working-class background influenced his writings.

From 1891 to 1898 Lawrence attended a boarding school in Eastwood that is today named in his honor: D.H. Lawrence Primary School. Lawrence was the first local student to win a scholarship to Nottingham High School. Lawrence had a great love of books while he was young and throughout his life.

From 1902 to 1906 Lawrence worked as a schoolteacher in Eastwood. It was around this time that he began writing his first poems and short stories. In 1907 Lawrence won a short story competition, and he began working on a draft for his first novel. Lawrence enrolled as a full-time student at the University of London in 1908 and he earned a teaching certificate there.

For a while, Lawrence both taught and submitted his writings for publication to some of the literary journals of the time. His first novel, The White Peacock, was published in 1911. The novel explored the theme of love triangles and the damage associated with mismatched marriages. The book received generally positive reviews, and that same year Lawrence quit his teaching position in order to be able to write full-time.

In 1912 Lawrence met the woman who he was to share his life with, Frieda Weekley, and although she was already married when they first met, they eloped and left England for Germany. Once in Germany Lawrence was arrested and accused of being a British spy, although, thanks to an intervention by Frieda’s father, he was released.

That same year, the Lawrences walked from Germany, across the Alps, to Italy. This magnificent journey, with sights of incredible beauty, and Lawrence’s impressions of the Italian countryside, were recorded in the first of Lawrence’s travel books, Twilight in Italy. During his time in Italy, Lawrence completed his novel Sons and Lovers, and he also spent time with his good friend Aldous Huxley. Lawrence’s novel, about the emotional conflicts associated with suffocating relationships and the realities of working-class life, was published in 1913 and received positive reviews.

While in Italy, Lawrence also wrote the draft of a manuscript that was eventually divided into two of his best-known novels, The Rainbow, published in 1915, and Women in Love, published in 1920 as a sequel. In both of these novels, lesbian characters play prominent roles, and the novels were considered highly controversial when they were published. They were initially banned in the United Kingdom for obscenity. In 1922 the Lawrences moved to the United States and settled in Taos, New Mexico.

Lawrence’s final novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, was first published privately in 1928, in Italy, and in 1929 in France. The story is about a young, married, upper-class woman who has an affair with her working-class gamekeeper, and the novel revolves around the theme that love can happen purely from physical expression.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover wasn’t openly published until 1960 when it became the subject of an obscenity trial in the United Kingdom for its depiction of sexual intimacy and its use of forbidden language. It was initially banned in the United States, Canada, Australia, India, and Japan. Lawrence’s publisher won the obscenity trial in the United Kingdom, three million copies of the book were quickly sold, and the bans was subsequently lifted around the world.

Lawrence’s work, opinions, and artistic preferences, were highly controversial during his lifetime, and there were many people who didn’t like what he was writing; as a result, he endured quite a bit of persecution and much misrepresentation of his work. Many critics viewed his erotic writings as pornography. However, although Lawrence’s depictions of sexuality were seen as shocking at the time that they were published, they seem rather tame by today’s standards.

There is also a deeper, almost mystical philosophy underlying Lawrence’s novels that many of his early critics missed. The leading characters in his most controversial novels go through rebirth experiences, and they grow into more fulfilling versions of themselves. Also, according to Lawrence, “the journey into the unconscious is accomplished through sensual experience.” This is an important theme for Lawrence. He urges us to explore the impulses and desires of the unconscious in order to find our deeper selves. Lawrence didn’t trust the intellect because he believed that the mind distorts reality, and that bodily sensations are more concrete and thus more real.

Lawrence also wrote five screenplays and nearly 800 poems in his lifetime. He had a lifelong interest in painting as well, and this became his main form of creative expression during his final years. In 1929 Lawrence’s paintings were exhibited at the Warren Gallery in London and the show was extremely controversial. Over 12,000 people attended, and after some people complained about the artwork, the police seized thirteen of the twenty-five paintings. Lawrence was able to get the paintings back— but only under the condition that he never exhibit them in England ever again. Lawrence’s paintings are now housed in a hotel in Taos, and in Austin at the University of Texas.

Lawrence died young, in 1930, at the age of 44, and he was buried in Taos. Since 2008, an annual D. H. Lawrence Festival has been organized in his hometown of Eastwood, to celebrate his life and works.

Some of the quotes that D.H. Lawrence is known for include:

Be still when you have nothing to say; when genuine passion moves you, say what you’ve got to say, and say it hot.

But better die than live mechanically a life that is a repetition of repetitions.

This is what I believe: That I am I. That my soul is a dark forest. That my known self will never be more than a little clearing in the forest. That gods, strange gods, come forth from the forest into the clearing of my known self and then go back. That I must have the courage to let them come and go. That I will never let mankind put anything over me, but that I will try always to recognize and submit to the gods in me and the gods in other men and women. There is my creed.

Life is ours to be spent, not to be saved.

I never saw a wild thing sorry for itself. A small bird will drop frozen dead from a bough without ever having felt sorry for itself.

One must learn to love, and go through a good deal of suffering to get to it, and the journey is always towards the other soul.

Bob is the author of over 35 popular fiction and nonfiction books, dealing with such themes as our future evolution, unexplained phenomena, synchronicity, the occult, quantum mechanics, altered states of consciousness, the nature of belief systems, and the link between science and mysticism, with wit, wisdom, and personal insights.

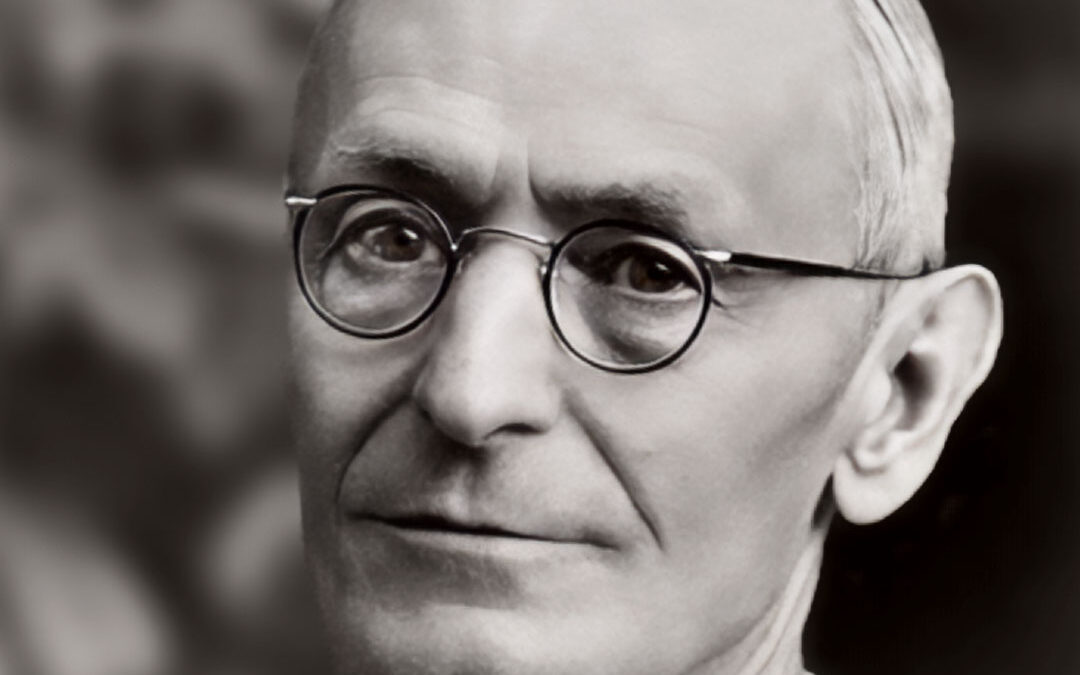

Bob was born “Robert Edward Wilson” in 1932 in Brooklyn, New York. He suffered from polio as a child and found effective treatment through the Kenny Method, an unconventional treatment using hot moist packs applied to the muscles, that the American Medical Association refused to acknowledge at the time. Lingering symptoms continued, and he walked with a cane due to post-polio muscle spasms, but as a result of his positive experience with the Kenny Method, Bob remained open to alternative medical perspectives throughout his life.

Bob attended Catholic grammar schools in New York before gaining admission into Brooklyn Technical High School. After his graduation from high school in 1950, he worked as an ambulance driver, engineering aide, and salesman. From 1952 to 1957 Bob studied electrical engineering and mathematics at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute and English education at New York University from 1957 to 1958.

It was in the late 1950s that Bob first began writing professionally, as a freelance journalist and advertising copywriter. Around this time is when he adopted his maternal grandfather’s name, “Anton,” for his writings. In 1958 Bob married Arlen Riley, and they remained married until her death in 1999.

In 1962 Bob edited two magazines, one in Ohio called Balanced Living, and a New York magazine called Fact. Then in 1965, Bob started a job at Playboy Magazine, where he worked as associate editor until 1971. Bob co-edited the magazine’s Playboy Forum, a section consisting of responses to letters, and it was here that ideas for his most famous work, The Illuminatus! Trilogy began to percolate.

Published in 1975, Bob coauthored the cult classic trilogy with his associate Playboy editor Robert Shea. The trilogy consists of three novels that weave together a surreal, satirical, science fiction adventure that revolves around a web of intertwined conspiracy theories and historical facts involving a hidden organization called the “Illuminati” that is secretly running the world. Some of Bob’s other well-known fiction books include Schrödinger’s Cat Trilogy, Masks of the Illuminati, and The Historical Illuminatus Chronicles.

In 1977 Bob published his autobiographical book Cosmic Trigger: Final Secret of the Illuminati. This was Bob’s personal story of how his “self-induced brain change” experiments affected him, and it contains a whirlwind of radical ideas. It’s the single most transformative book that I’ve read in my life, and it inspired my career as a writer. Many of the people that I’ve interviewed—such as Timothy Leary and John Lilly — I first learned about from this extraordinary book. Bob later published two additional Cosmic Trigger volumes, and some of his other non-fiction books include The New Inquisition, Right Where You Are Sitting Now, and Quantum Psychology, which I wrote the introduction to in the latest edition.

Bob went back to school in the late 1970s and early 1980s. He received his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in psychology from Paideia University in California in 1978, and his Ph.D. in 1981. His dissertation on the 8-circuit model of consciousness, first developed by Timothy Leary, was reworked and later published in 1983 as Prometheus Rising, which became one of his most popular books.

In 1981 Bob and Arlen moved to Dublin, Ireland, where they lived for six years. They moved to Los Angeles in 1987, and to Capitola, California in 1995. Bob was a huge admirer of James Joyce and was an expert on his literary work. Bob once remarked, “Dublin, to me, is a James Joyce theme park.”

Bob had a remarkable talent for leading his readers into a perspective where they question assumptions that they didn’t even know that they had, and redefine their unconsciously-constructed notions of reality. He had an uncanny ability to guide people, unsuspectingly, into a mutable state of mind where they are playfully tricked into “aha” experiences that cause them to question their most basic assumptions about what is real and what isn’t. Remarkably, he accomplished this with a wonderful sense of humor, and his writings had a powerful, shamanic quality to them.

I first met Bob at one of his lectures in Santa Cruz in 1988. At the end of his talk, I asked him if he would consider writing a blurb for the back cover of my first book, which I was working on at the time. He didn’t respond with much enthusiasm, as though he got asked this question too many times that day, but he said to have my publisher send him a copy. You can only imagine my excitement when I later learned that he wrote an 11-page introduction to the book, Brainchild,” and Carolyn did the artwork for the cover!

From 1989 to 2007 I saw Bob at least once a week when I attended book readings, discussions, movie nights, celebrations, and other gatherings at his home in Los Angeles and then in Capitola. We read from great literary works, such as Joyce’s Ulysses, Ezra Pound’s The Cantos, and Bob’s own Illuminatus! Trilogy. We watched films by Orson Wells and episodes of The Prisoner.” Our friends Valerie Corral, Nick Herbert, and others used to come regularly. It was the best of times.

One evening in the early 1990s I brought Carolyn and Oz Janiger over to meet Bob and Arlen when they were living in Los Angeles. At the time Carolyn had an art exhibit at the Gallerie Illuminati in Santa Monica, which was a striking synchronicity that night.

Bob participated in the roundtable discussions on technology and consciousness with Carolyn and me (along with Ralph Abraham, Nina Graboi, Nick Herbert, Rebecca Novick, and Stephen LaBerge) at UC Santa Cruz in 1993. He sat across from Carolyn on the stage during the event— Mavericks of the Mind Live!— which was recorded by Sound Photosynthesis.

Bob died in 2007 at his home in Capitola. I miss him dearly. Bob had an uncanny ability to perceive things that few people notice, and he had an extraordinarily wide and well-integrated interdisciplinary mind, with an incredible memory. He had an encyclopedic knowledge of many different fields— ranging from literature and psychology to quantum physics, Buddhism, and neuroscience.

Despite some serious personal challenges over the years, Bob always maintained a strongly upbeat, optimistic, and perpetually cheerful perspective on life, and— regardless of the circumstances, and up until his final moments — he never failed to make me smile every time I saw him. Everyone who was fortunate enough to know him agreed; there was something truly magical about Robert Anton Wilson.

I interviewed Bob in 1989 for my book Mavericks of the Mind, which includes my interview with Carolyn. (Exciting news: The third edition of Mavericks of the Mind will be published next year by Hilaritas Press — more on this soon!) I interviewed Bob again in 2003 for my book Conversations on the Edge of the Apocalypse. Here is an excerpt from our conversation:

David: Synchronicity is a major theme that runs through your books. What model do you use at present for interpreting this mysterious phenomenon?

Bob: I never have one model. I always have at least seven models for anything.

David: Which one is your favorite?

Bob: Bell’s Theorem combined with an idea I got from Barbara Honegger, a parapsychologist who worked for Reagan. . . . Long before Barbara became a controversial political figure, she gave me the idea that the right brain is constantly trying to communicate with the left. If you don’t listen to what it’s trying to say, it gives you more and more vivid dreams, and if you still won’t listen, it leads to Freudian slips. If you still don’t pay attention, the right brain will get you to the place in space-time where synchronicity will occur. Then the left brain has to pay attention. “Whaaaat!?”

David: What do you think happens to consciousness after physical death?

Bob: Somebody asked a Zen master, “What happens after death?” He replied, “I don’t know.” And the querent said, “But you’re a Zen master!” He said, “Yes, but I’m not a dead Zen master.” Somebody asked Master Eckart, the great German mystic, “Where do you think you’ll go after death?” He said, “I don’t plan to go anywhere.” Those are the best answers I’ve heard so far. My hunch is that consciousness is a non-local function of the universe as a whole, and our brains are only local transceivers. As a matter of fact, it’s a very strong hunch, but I’m not going to dogmatize about it.

I was systematically reading through Hermann Hesse’s novels when I first met Carolyn in 1983, and we have both really enjoyed his inspiring books and other creative output.

Hesse was a brilliant German-Swiss novelist, poet, and painter who lived between 1877 and 1962. Some of his most well-known books include Siddhartha, Demian, Steppenwolf, and Magister Ludi: The Glass Bead Game, which are my favorites as well. Each book explores a similar theme, of an individual’s efforts to break free from the established modes of civilization, and begin a quest for self-knowledge and spiritual understanding.

Hesse was born in Calw, Germany and he later became a citizen of Switzerland. Hesse began working in a bookstore in Tübingen as a teenager, and at the end of his twelve-hour shifts, he worked on his own writing. His first publication came in 1896, with his poem Madonna in a Viennese magazine, and later that year this was followed by the publication of a small volume of his poetry titled Romantic Songs. Hesse’s first poetry collection wasn’t met with much success— it only sold 54 copies in two years— and Hesse’s mother didn’t like the poems, calling them “vaguely sinful,” which was upsetting to Hesse.

In 1899 Hesse began working at another bookstore in Basel, and spent much time alone, engaged in self-exploration. Due to an eye condition, in 1900 he was exempted from compulsory military service, and he suffered from nerve disorders and persistent headaches throughout his life.

In the early years of the last century, Hesse published more poems and some short prose in journals. In 1904 Hesse’s novel Peter Camenzind was published, and this was a breakthrough novel for him, as from this point on, Hesse could now earn a living as a writer. The novel became popular throughout Germany, and the Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud praised Peter Camenzind as one of his favorite novels.

Hesse’s parents had a profound influence on his spirituality, and he said of his parents that, “their Christianity, one not preached but lived, was the strongest of the powers that shaped and molded me.” Self-exploration and spiritual development became important themes in many of Hesse’s writings. There was a ‘quest for enlightenment or self-realization’ theme in his books Siddhartha, Journey to the East, and Narcissus and Goldmund, and he often drew from Buddhism, Hinduism, and other Eastern philosophies in his novels. Hesse saw value in the varied forms of spiritual expression, and said, “For different people, there are different ways to God.”

Hesse is the author of 29 books. He also began painting when he was in his early 40s, and he created a legacy of around 3000 beautiful watercolors. The book Trees: An Anthology of Writings and Paintings collects Hesse’s poems and essays on the subject of trees and is accompanied by 31 of his watercolor illustrations, and the book Hesse as Painter collects 20 of his watercolors.

In 1946 Hesse received the Nobel Prize in Literature for his book Magister Ludi: The Glass Bead Game. However, despite Hesse’s status as a Nobel laureate, when Hesse died in 1962, his work wasn’t very well known in the United States. In fact, in the obituary that The New York Times published after Hesse’s death, said that his work was largely “inaccessible” to American readers.

This all changed in the mid-1960s when Hesse’s books suddenly became bestsellers in the U.S., and within the span of a few years, he became the most widely read and translated European author of the 20th century. The revival in popularity of Hesse’s works has been credited to their association with some of the popular themes of the 1960s counterculture, and according to Bernhard Zeller’s autobiography on Hesse, “in large part, the Hesse boom in the United States can be traced back to enthusiastic writings by two influential counterculture figures: Colin Wilson and Timothy Leary.”

Hesse’s work has had a considerable cultural influence. The band Steppenwolf took its name from Hesse’s novel with that title, and there is also a theater in Chicago called The Steppenwolf Theater. Throughout Germany, many schools are named after Hesse. Hesse’s novel Siddhartha required reading in my high school English class, which is how I first discovered his work.

Some quotes that Hermann Hesse is remembered for include:

“I have always believed, and I still believe, that whatever good or bad fortune may come our way we can always give it meaning and transform it into something of value.”

Learn what is to be taken seriously and laugh at the rest.

Wisdom cannot be imparted. Wisdom that a wise man attempts to impart always sounds like foolishness to someone else … Knowledge can be communicated, but not wisdom. One can find it, live it, do wonders through it, but one cannot communicate and teach it.

Whoever wants music instead of noise, joy instead of pleasure, soul instead of gold, creative work instead of business, passion instead of foolery, finds no home in this trivial world of ours.

I have been and still am a seeker, but I have ceased to question stars and books; I have begun to listen to the teaching my blood whispers to me.”

“Some of us think holding on makes us strong but sometimes it is letting go

Carolyn and I have both seem evidence of Hesse’s influence in one another’s writings. On the back cover of my first book, Brainchild, Carolyn wrote. “Brown is the Hesse of our time.” Similarly, in the introduction to Carolyn’s book The Alchemy of Possibility, I wrote, “Following the tradition of William Blake and Hermann Hesse, The Alchemy of Possibility is a poetic blend of mysticism and imagination.”

I first started enjoying Anaïs Nin’s erotic stories when I was in my early twenties, and I was intrigued by the encounters with Henry Miller that she described in her diaries. (Henry Miller is another author that Carolyn and I both admire, and who will be the subject of a future profile.) When I first met Carolyn we discussed Nin’s writings, and I was most interested to learn that Carolyn had met and corresponded with Nin years earlier.

Born in France, Anaïs Nin lived from 1903 to 1977 in major European and American cities during culturally vibrant times, where she recorded her personal encounters with many brilliant and creative minds. Nin spent her early years growing up in Spain and Cuba and then lived in Paris, New York, and Los Angeles. Nin was known for her prolific and varied writings that included celebrated essays, novels, and short stories, as well as her seven published volumes of diaries, and revolutionary volumes of erotica.

When Nin was in her late twenties, she developed a strong interest in psychoanalysis and studied it in depth— with René Allendy and Otto Rank— both of whom also became lovers, as she recounts in her diaries. Nin famously kept detailed journals of her private thoughts and intimate relationships, from the age of eleven until the end of her life. Many of these diaries were published during her lifetime and remain in print to this day. The revealing diaries that she kept included descriptions of her personal relationships with many well-known literary figures and intellectuals, such as John Steinbeck and Gore Vidal, and have unique historical value.

Some of the quotes that Anaïs Nin is remembered for include:

We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.

And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom.

Life shrinks or expands in proportion to one’s courage.

Nin has been lauded by critics for being one of the first and finest writers of women’s erotica, and much of her passionate, taboo-breaking work was published posthumously amid renewed critical interest in her life and work that continues to this day.