Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

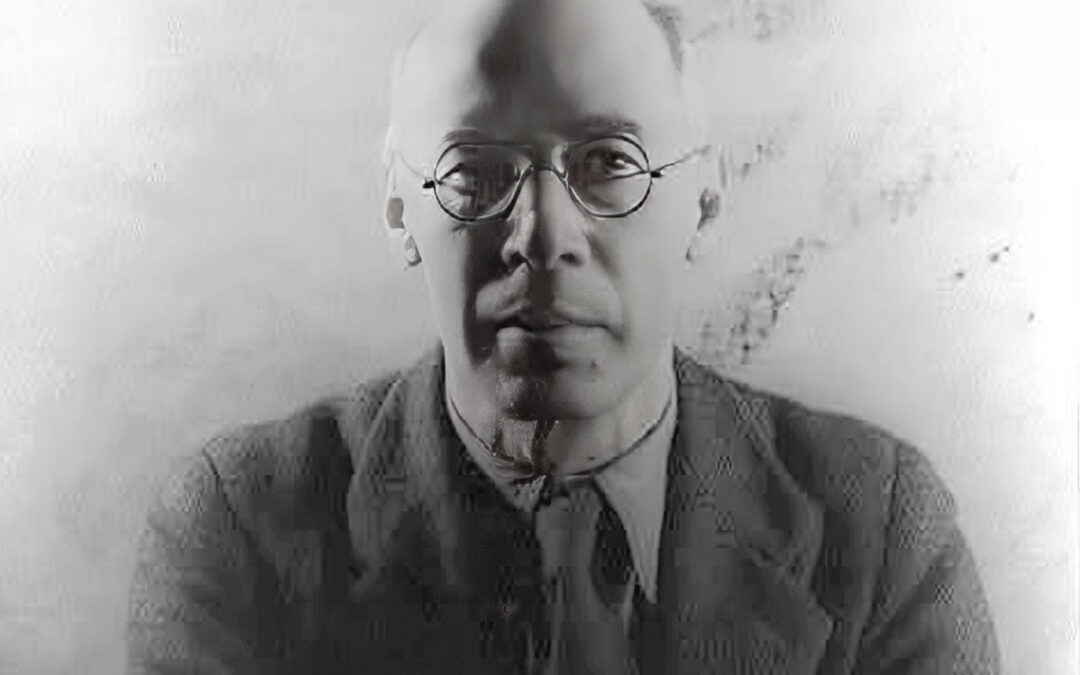

Carolyn and I have celebrated numerous events at the Henry Miller Memorial Library in Big Sur over the years, and she has had many poetry readings there. Located on the Pacific Coast Highway, and nestled among the glorious redwood trees, this beautiful library documents the life of the late author and artist Henry Miller, and also serves as a performance venue and art gallery, where local artists can exhibit their work. It’s a magical place that is cherished by the local community and loved by the many international visitors passing through Big Sur, where Henry Miller is remembered as a legendary figure.

Henry Miller is another brilliant writer whom Carolyn and I have both admired. His semi-autobiographical novel Tropic of Cancer was a creative whirlwind that blew my mind apart when I first read it in my early twenties. Miller’s writing was a revolution; he created his own unique literary style, combining actual events from his life, with fantasies and exaggerations, as well as explicit sexuality, philosophical reflections, surrealist free association, Eastern philosophy, and mysticism.

Some of Miller’s most famous books, which were based upon his experiences in New York and Paris— such as Tropic of Cancer (first published in 1934), and Black Spring — were controversial when they were first published, largely due to their explicit sexual descriptions, and were officially banned in the United States until 1964. Tropic of Cancer was published in 1961 by the Grove Press in the U.S., challenging the ban. This led to obscenity trials, resulting in the Supreme Court’s official lifting of the ban in 1964. However, Miller’s banned books had been smuggled into the U.S. prior to 1961, and he built an underground reputation in the States before the ban was officially lifted.

Miller’s later works were less sexually explicit, more philosophical, and often critical of consumerism in America— such as The Air-Conditioned Nightmare, which was published in 1945, and also introduces elements of Hindu philosophy. Miller’s impressionist travelogue The Colossus of Maroussi, about his nine months in Greece in 1939, is frequently considered his best book. Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch, another favorite, was published in 1957 and is a collection of wonderful stories about his time in Big Sur, and the extraordinary people that he met.

Some quotes that Henry Miller is remembered for include:

The aim of life is to live, and to live means to be aware, joyously, drunkenly, serenely, divinely aware.

The one thing we can never get enough of is love. And the one thing we never give enough of is love.

I need to be alone. I need to ponder my shame and my despair in seclusion; I need the sunshine and the paving stones of the streets without companions, without conversation, face-to-face with myself, with only the music of my heart for company.

Develop an interest in life as you see it; the people, things, literature, music – the world is so rich, simply throbbing with rich treasures, beautiful souls and interesting people. Forget yourself.

Miller was a powerhouse of creative energy. In addition to his revered literary abilities, Miller was also an accomplished artist who produced several thousand watercolor paintings and published several books of his artwork.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to interview Henry Miller, although I would have loved to; he died years before I started doing interviews.

Photo by Bettmann

British writer, philosopher, and social satirist Aldous Huxley’s work has had a profound impact on Carolyn and I, and our dear friends Oz Janiger and Laura Huxley told us wonderful stories about their precious time with him.

Aldous Leonard Huxley was born in 1894 in Surrey, England. He was born into an intellectually active family; his father was a schoolteacher and writer, and his mother founded an independent girls’ boarding and day school. Aldous was the grandson of the famous zoologist Thomas Huxley, who was an early advocate for Darwin’s theory of evolution, and his brothers Julian and Andrew became noteworthy biologists.

Aldous’ father, Leonard Huxley, had a well-equipped botanical laboratory where Aldous began his science education as a child. His brother Julian described him as someone who “frequently contemplated the strangeness of things.”

Aldous faced some serious challenges as a teenager. In 1908 his mother died, and in 1911 he contracted an eye disease that caused the surface of his eyes to become inflamed. This ocular inflammation left him almost blind for around three years, and then he partially recovered, with one eye just capable of light perception, and the other with about 5 percent of normal vision. Unable to pursue a career in medicine, as he had initially intended, due to his loss of sight, Huxley studied English literature at Oxford from 1913 to 1916.

After graduating from Oxford, Aldous taught French for a year at Eton College in Berkshire. One of his students at the time was a young fellow named Eric Blair, who also went on to become a well-known writer; he took the pen name George Orwell and wrote the classic dystopian novel 1984.

In 1916 Aldous edited the Oxford Poetry journal, and he completed his first (although unpublished) novel at the age of 17. In 1921 Aldous published his first novel, Crome Yellow, which, like the novels that followed— Antic Hay in 1923, Those Barren Leaves in 1925, and Point Counter Point in 1928, were social satires.

In 1919 Aldous married his first wife, Maria Nys, and they had one child together, Matthew (who Carolyn and I met at a conference during the 1990s). Aldous and Maria lived with Matthew in Italy during the 1920s, where Aldous would spend time with his friend, English novelist and poet D. H. Lawrence.

In 1932 Aldous published his most well-known work, Brave New World, a dystopian novel about a World State in the future, where citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hierarchy. The book has since become a classic of modern literature— it ranked number 5 on a list of the 100 best-selling English-language novels of the 20th Century — and carried a profound warning about the dangers of social control that seem especially relevant today.

In 1937 Aldous moved to Los Angeles with his wife Maria, where he worked as a screenplay writer for Hollywood films. Aldous received screen credit for Pride and Prejudice in 1940, and he worked on a number of other films, including Jane Eyre in 1944. In 1955 Aldous’ wife Maria died.

Aldous grew interested in philosophical mysticism and in 1945 he published The Perennial Philosophy, which explores the common ground between Eastern and Western mysticism. Our beloved friend Laura Huxley first met Aldous in 1948, when she was pursuing an idea for a film, and although the film was never produced, they stayed close and were married in 1956. Laura was married to Aldous for the last 7 years of his life.

In 1953 Canadian psychiatrist Humphry Osmond introduced Aldous to a psychedelic medicine, mescaline, and he had a powerful mystical and transcendent experience that became the basis for his revolutionary book The Doors of Perception. It’s a slim volume, just 63 pages, but it had a powerful cultural impact and is generally regarded as one of the most important books on psychedelic mysticism. The popular rock band The Doors took their name from the title of Huxley’s book.

In 1962 Aldous published his final novel, Island, a utopian fantasy about a shipwrecked journalist on a fictional island, which incorporates the insights that he gained from his mystical experiences, and provides a wonderful alternative future to his dystopian vision in Brave New World. During his lifetime, Aldous published more than 50 books, and a large selection of poetry, short stories, articles, philosophical treatises, and screenplays.

Aldous died in 1963, on the same day that John F. Kennedy was assassinated. On his deathbed, Aldous asked Laura to administer LSD to him and he died while undergoing a psychedelic experience, as Laura read to him from The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Laura wrote about this experience, and her final days with Aldous, in her much-loved book This Timeless Moment.

Laura shared a favorite story with me about Aldous. She told me about this one time that Aldous was at a meeting of professional scientists, and how he was asked what final words of advice he could offer after a lifetime of inquiry. His response was, “I’m very embarrassed because I worked for forty years. I studied everything around. I did experiments. I went to several countries. And all I can tell you is to be just a little kinder to each other.”

Some of the quotes that Aldous is known for include:

After silence, that which comes nearest to expressing the inexpressible is music.

I wanted to change the world. But I have found that the only thing one can be sure of changing is oneself.

Most human beings have an almost infinite capacity for taking things for granted.

The more powerful and original a mind, the more it will incline towards the religion of solitude.

That men do not learn very much from the lessons of history is the most important of all the lessons that history has to teach.

Consistency is contrary to nature, contrary to life. The only completely consistent people are the dead.

The secret of genius is to carry the spirit of the child into old age, which means never losing your enthusiasm.

There are things known and there are things unknown, and in between are the doors of perception.

I wish so much that I had had an opportunity to interview Aldous, but I was only 2 years old when he died.