Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of Bengali poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, painter, and social reformer Rabindranath Tagore, who reshaped Bengali literature and music, as well as Indian art, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His spiritually-inspired poetic songs and elegant prose were widely popular in the Indian subcontinent, and he was the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Tagore was also a strong advocate for Indian independence and global humanism, and his compositions, including the national anthems of India and Bangladesh, continue to inspire to this day.

Rabindranath Tagore was born in 1861 in Calcutta, Bengal. He was born into a prominent and wealthy family, and he was the youngest of 13 surviving children. Tagore’s father was an Indian philosopher and religious reformer, who was the founder of the Brahmo religion. His mother died in his early childhood, and his father traveled widely, so he was mostly raised by servants. Tagore’s family was at the forefront of the Bengal Renaissance, and they hosted the publication of literary magazines, as well as theatre and recitals of Bengali and Western classical music.

Tagore’s early years were shaped by the rich cultural environment of his family household. He was primarily educated at home, where he was exposed to classical music, literature, and the arts. Tagore’s father invited several professional musicians to stay at their house and to teach Indian classical music to the children. Tagore started writing poetry when he was eight years old. Although he attended various schools, Tagore disliked formal education and found traditional schooling restrictive, preferring instead to learn through exploration and observation of the world around him.

In 1873, Tagore accompanied his father on a journey for several months to northern India, which included a stay in the Himalayas, and this had a profound influence on him. During this period, Tagore began to write poetry more seriously, and in 1874, his first poem was published in a Bengali magazine.

Tagore began exploring different literary forms besides poetry. In 1877, he wrote his first short story, Bhikharini (The Beggar Woman), and his first drama, Valmiki Pratibha, which was based on the legend of Ratnakara, a thug who later became Sage Valmiki and composed the Hindu epic Ramayana. In 1882, he wrote Nirjharer Swapnabhanga (The Fountain Awakens from its Dream), which was a celebrated poem that marked his breakthrough into the literary world. During this period, his works reflected a blend of classical and modernist influences, and he helped to modernize Bengali literature.

In 1883, Tagore married Mrinalini Devi, with whom he would have five children. In the late 1880s, he also took over the management of his family’s estates in rural Bengal and did this for several years. This brought him into closer contact with the lives of common people, and he developed a deep connection with village life. This experience deepened his empathy with rural communities and it influenced his later works— particularly in his expressing themes of social justice and rural life— and he produced some of his most notable short stories, such as those in Galpaguchchha (A Bunch of Stories).

In 1894, Tagore wrote the collection Sonar Tari (The Golden Boat), a key work reflecting his evolving poetic style. By the end of the 1890s, Tagore’s literary reputation in Bengal had grown significantly, and he began to be recognized as a major cultural figure.

In 1901, Tagore founded a progressive school, Santiniketan, which focused on holistic, nature-centered learning, and aimed to combine traditional Indian education with Western ideas. During this period, Tagore’s literary output remained prolific, and he wrote several significant works, including Naivedya” and Kheya, which reflected his spiritual and philosophical ideas. In 1905, Tagore became actively involved in the Swadeshi movement, which opposed the British partition of Bengal.

In 1910, Tagore published Gitanjali (Song Offerings), a collection of deeply spiritual poems. Two years later, he traveled to England with his son and this collection of poems. During the long sea voyage from India to England Tagore began translating this latest selection of poems into English. Most of his work before that time had been written in his native tongue of Bengali, and he made the handwritten translations in a little notebook that he carried around with him.

When they arrived in England, Tagore’s son accidentally left his briefcase with this notebook in the London subway, and Tagore feared it was lost forever. Fortunately, an English woman turned in the briefcase and it was recovered on the next day. Tagore had one friend in England at the time, an artist that he had met in India named Rothenstein. When Rothenstein learned of Tagore’s translated poems, he asked to see them. As the story goes, Tagore was reluctant, but after much persuasion by Rothenstein, Tagore let him have the notebook, and the artist was blown away by the poems.

Rothenstein was so moved by the poetry that he contacted his friend, Irish poet, and writer William Butler Yeats, and he talked him into looking at the hand-scrawled notebook of poems. Yeats was also deeply impressed, so much so that he wrote the introduction to Gitanjali when it was published later that year in London. The poetry was an instant sensation in London literary circles, and it soon gained immense recognition and brought Tagore international acclaim.

In 1913, Tagore became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, for his collection Gitanjali, which had almost been lost in the London subway. The incident highlights the serendipitous nature of the manuscript’s survival, which went on to change Tagore’s life and bring him international fame. Tagore used his Nobel Prize money to expand his school, Santiniketan, into a full-fledged university, Visva-Bharati, reflecting his continued commitment to education. Tagore gained greater prominence as an international intellectual, and he advocated for Indian independence, cultural exchange, and global peace.

In 1915, Tagore was granted a British knighthood for his exceptional contributions to literature. However, in 1919, he renounced his British knighthood in protest of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, signaling his strong opposition to British colonial rule. During this period, Tagore traveled extensively across Europe, America, and Asia, delivering lectures and promoting his ideas on cultural exchange, humanism, and education.

In 1921, at the age of 60, Tagore took up drawing and painting, and he had successful exhibitions of his many works. He made a debut appearance in Paris, and he had showings throughout Europe. It is thought that Tagore was likely red and green color blind, and his works exhibited unusual color schemes and off-beat aesthetics. He also continued writing prolifically, producing works like Gora in 1923, and The Religion of Man in 1922, which explored themes of identity, spirituality, and universalism.

Tagore continued to travel extensively, visiting countries such as Argentina, Japan, and China, as well as more of Europe, where he met with intellectuals, artists, and political figures, further spreading his ideas on humanism, cultural unity, and education. Tagore also continued his literary work, publishing notable pieces such as Fireflies in 1928, and The Home and the World in 1916, which explored the tensions between nationalism and personal freedom. In 1930, Tagore delivered the Hibbert Lectures at Oxford University, which were later published as The Religion of Man, reflecting his evolving philosophy on spirituality and human connection.

Tagore’s spiritual perspective was deeply rooted in a belief in the unity of all existence and a divine presence that transcends religious boundaries. He viewed spirituality as an intimate, personal connection with the divine, expressed through nature, art, and human relationships. Tagore rejected dogmatic religious practices, favoring a more inclusive and universalist approach that emphasized love, compassion, and the interconnectedness of humanity. His works often explore the divine, not as a distant entity, but as an integral part of everyday life, and he advocated for a harmonious balance between the material and spiritual worlds.

Tagore also helped to bridge science and spirituality. He was one of the first people to try and combine Eastern and Western cultures, as well as ancient wisdom and modern physics. He was quite knowledgeable of Western culture and science. Tagore was a good friend of Indian physicist Satyendra Nath Bose, and he had a good grasp of contemporary physics. He was so knowledgeable that he was well able to engage in a debate with Albert Einstein in 1930 on the newly emerging principles of quantum mechanics and chaos. Tagore’s meetings and tape-recorded conversations with Einstein, and other contemporaries such as H.G. Wells, stand out as cultural landmarks.

In 1934, Tagore published Char Adhyay and Shesher Kobita, which explored themes of love, identity, and modernity. In 1937, he suffered a severe illness but recovered, continuing to write poetry, plays, and essays that reflected his philosophical and spiritual musings. Tagore also remained deeply involved in his educational institution, Visva-Bharati, and maintained his commitment to social reform, particularly advocating for rural development and education.

In 1939, Tagore became ill, but he remained active in his literary work, producing some of his most reflective and introspective poetry, which meditated on life, death, and the nature of existence. He continued to oversee the activities of his school, Visva-Bharati, which had become a prominent educational institution. In 1940, Oxford University honored him with a Doctorate of Literature in recognition of his contributions to global literature.

In 1941, at the age of 80, Tagore died in Calcutta. He left behind a vast legacy as a poet, philosopher, educator, and cultural icon whose influence extended far beyond India. He revolutionized Bengali literature and music, bringing modernism and deeply spiritual themes into his works. His progressive educational model at Visva-Bharati University remains influential. Tagore’s advocacy for cultural exchange, humanism, and Indian independence left a lasting impact on global intellectual thought. His compositions, including the national anthems of India and Bangladesh, continue to inspire, and his ideas on spirituality, social justice, and education resonate worldwide today.

There are eight Tagore museums, three in India and five in Bangladesh. Every year, many events pay tribute to Tagore. His birth anniversary is celebrated by groups across the globe. There is an annual Tagore Festival held in Urbana, Illinois. There are also walking pilgrimages in West Bengal, India, from Kolkata to Santiniketan, and recitals of his poetry, which are held on important anniversaries.

Some of the quotes that Rabindranath Tagore is known for include:

It is very simple to be happy, but it is very difficult to be simple.

I seem to have loved you in numberless forms, numberless times, in life after life, in age after age forever.

Death is not extinguishing the light; it is only putting out the lamp because the dawn has come.

A mind all logic is like a knife all blade. It makes the hand bleed that uses it.

Let your life lightly dance on the edges of Time like dew on the tip of a leaf.

By plucking her petals you do not gather the beauty of the flower.

Music fills the infinite between two souls.

I slept and dreamt that life was joy. I awoke and saw that life was service. I acted and behold, service was joy.

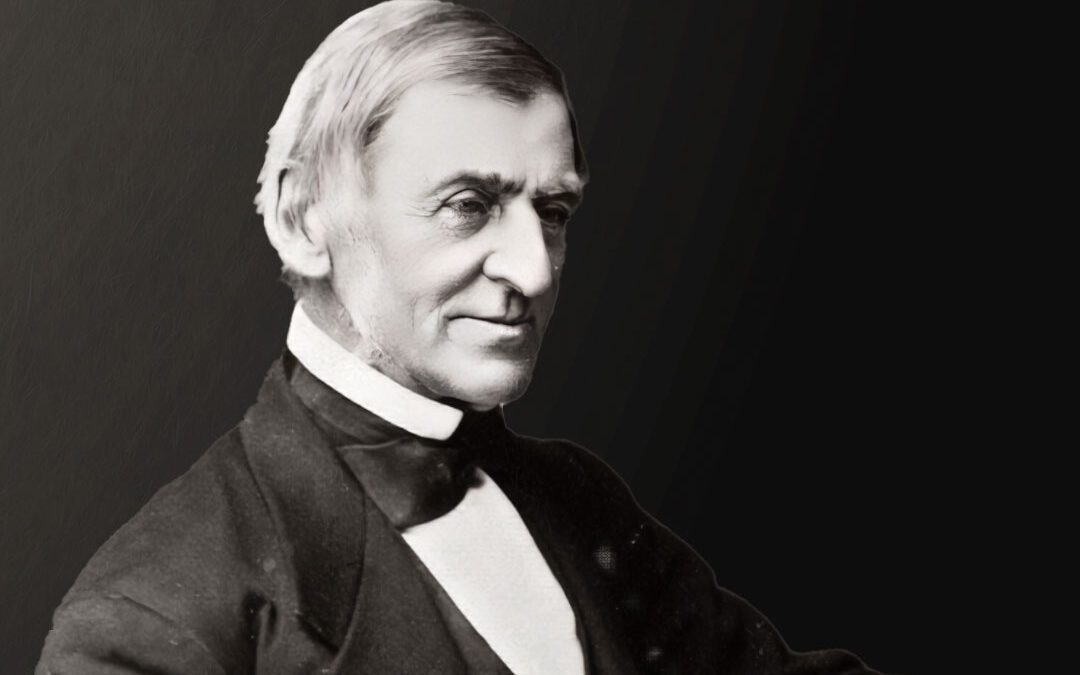

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of writer, speaker, poet, and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, who led the Transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century and is considered one of America’s most influential thinkers. He was regarded as a champion of individualism and critical thought, and a critic of the societal pressures that push toward conformity. In other words, he was one of the original spokespeople for ‘doing your own thing’ and ‘thinking for yourself’.

Ralph Waldo Emerson was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1803. His father was a Unitarian minister, who passed away when he was only eight, leaving his mother to raise him and his five siblings in modest circumstances. Despite financial challenges, his childhood was marked by intellectual influence, particularly from his aunt, who encouraged his love for reading and philosophical inquiry.

Emerson attended the Boston Latin School, where he excelled academically, and in 1812, he entered Harvard College at the age of 14. During these years, he developed a deep interest in literature and writing, while also grappling with the pressure to follow in his father’s footsteps as a minister. In 1821, when he was 18, Emerson served as Class Poet, and he presented an original poem on Harvard’s Class Day, a month before his graduation. That year Emerson graduated from Harvard College and then briefly worked as a schoolteacher, although he found this occupation unfulfilling.

In 1823, Emerson entered Harvard Divinity School, following a path toward ministry. However, during this period, he began to question some of the traditional religious doctrines of his time. In 1825, he was licensed to preach, preparing for a career as a Unitarian minister. However, he wasn’t sure that he wanted to do this, due to the questions that he had about conventional theology.

In 1826, Emerson faced some health challenges, which led him to leave his ministry studies temporarily. He was ordained as a Unitarian minister in 1829, and in the same year, he married Ellen Louisa Tucker, whose death from tuberculosis in 1831 deeply affected him. This tragedy, combined with growing dissatisfaction with traditional religious practices, led Emerson to resign from the ministry in 1832. In 1833, he traveled to Europe, meeting influential thinkers like Thomas Carlyle and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, which deepened his philosophical insights. In 1835, Emerson settled in Concord, Massachusetts, and he began establishing himself as a leading voice in Transcendentalism, which he felt a strong resonance with.

Transcendentalism was a philosophical and literary movement in the early 19th century that emphasized the inherent goodness of people and nature, as well as the importance of individual intuition and spiritual experience. It rejected organized religion and materialism, advocating for self-reliance, personal freedom, and a deep connection to the natural world as pathways to understanding higher truths. Transcendentalists believe that true knowledge transcends empirical observation and can be accessed through inner reflection and communion with nature. The movement sought to challenge the conformity of society and inspire a more profound spiritual and intellectual awakening.

In 1836, Emerson published his essay Nature, which laid the foundation for Transcendentalist philosophy. In this essay, Emerson divides nature into four usages: Commodity, Beauty, Language, and Discipline. These distinctions define the ways by which humans use nature for their basic needs, their desire for delight, their communication with one another, and their understanding of the world. That same year, Emerson helped found the Transcendental Club, which gathered together like-minded thinkers.

In 1837, Emerson met poet and philosopher Henry David Thoreau. At that time, Thoreau was a young graduate from Harvard. Their initial meeting happened when Thoreau attended one of Emerson’s lectures. Impressed by Thoreau’s intellectual potential, Emerson invited him into his circle of Transcendentalist thinkers. The two became good friends as they shared common ideas about nature, individualism, and Transcendentalism. Emerson was a mentor to Thoreau, encouraging him to write and think independently. Their relationship deepened when Thoreau lived in a small cabin on Emerson’s land at Walden Pond from 1845 to 1847, during which time Thoreau wrote much of Walden. Although their friendship had occasional tensions— mainly because of differences in their philosophies— it remained a significant intellectual bond throughout their lives, and Emerson referred to Thoreau as his “best friend.”

In 1837, Emerson delivered his lecture, The American Scholar at Harvard, calling for intellectual independence, and this was hailed by Transcendentalists as America’s “intellectual Declaration of Independence.” In 1841, Emerson also published Essays and a year later Essays: Second Series, which contained some of his most famous essays, like Self-Reliance and The Over-Soul, establishing his reputation as a major American thinker and writer.

Emerson’s spiritual perspective centered on the belief that divinity resides within each individual and that spiritual truth can be accessed through personal intuition rather than organized religion. He viewed nature as a direct manifestation of the divine, advocating for a deep, personal connection with the natural world as a means to understand higher spiritual truths. Emerson rejected traditional religious dogma, emphasizing self-reliance, inner wisdom, and the unity of all creation. His spiritual philosophy, influenced by Transcendentalism, celebrated the individual’s direct experience of the divine and the idea that every person has the capacity for profound spiritual insight.

In the 1840s, Emerson had a brief venture into beekeeping. Inspired by his deep connection to nature, he decided to try beekeeping at his home in Concord. However, the experiment didn’t last long. When one of his hives was destroyed by a bear, Emerson abandoned the endeavor. Despite this, the experience reflected his hands-on approach to understanding nature, which he so often wrote about.

In 1847, Emerson traveled to Europe for a second time, delivering lectures that further enhanced his international reputation. Upon returning to the U.S. in 1850, Emerson published his work Representative Men, which profiled historical figures like Plato and Shakespeare, exploring the nature of genius. Throughout the 1850s, Emerson increasingly engaged with social and political issues. In 1855, he read and praised Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, recognizing Whitman as a powerful new voice in American literature. Whitman called Emerson his “master.”

In 1857, Emerson co-founded the literary and cultural magazine The Atlantic Monthly with some of his friends, and the magazine is published to this day during the Civil War. Emerson strongly supported the Union cause and the abolition of slavery, sometimes speaking and writing against it, although he was hesitant about lecturing on the subject due to concerns about being in the public limelight about this. In 1862, Emerson delivered a eulogy for his friend Thoreau, who died at the age of 44 of tuberculosis. In 1860, Emerson’s The Conduct of Life was published, a collection of essays addressing themes of fate, power, and wealth. In 1867, Emerson‘s health began to decline, although he remained a prominent intellectual, celebrated for his contributions to American thought and literature. Friedrich Nietzsche said that he was “the most gifted of the Americans.” In 1870, Emerson published Society and Solitude, a collection of essays that reflected his mature thoughts on personal reflection and societal roles.

In 1871 or 1872, Emerson started experiencing memory problems and he suffered from aphasia, a disorder that affects how one communicates. By the end of the decade, he sometimes forgot his name. However, if asked how he felt, he would respond, “Quite well; I have lost my mental faculties, but am perfectly well.” Despite his declining memory and mental sharpness, he remained active in public life and continued lecturing until the mid-1870s. In 1872, his house in Concord was damaged by fire, but it was quickly rebuilt with the help of friends and admirers. Around 1875, Emerson’s public appearances became less frequent due to his deteriorating health. His last significant public event was in 1878 when he attended the unveiling of a statue of The Minute Man in Concord.

In 1882, Emerson fell ill with pneumonia and he passed away that year at his home in Concord. His death marked the end of an era for American intellectual life, and he was widely mourned. Emerson was buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, near the graves of other prominent Transcendentalists.

As a pioneering philosopher, essayist, and poet, Emerson profoundly shaped American intellectual and literary culture. As a leader of the Transcendentalist movement, he championed individualism, self-reliance, and the deep connection between humans and nature, influencing generations of thinkers, writers, and social reformers. Emerson’s ideas contributed to the development of American pragmatism, environmental thought, and the rise of social movements such as abolitionism and women’s rights, and his essays remain foundational texts in American philosophy, promoting personal freedom and spiritual exploration.

Some of the quotes that Ralph Waldo Emerson is known for include:

To be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you something else is the greatest accomplishment.

For every minute you are angry you lose sixty seconds of happiness.

Live in the sunshine, swim the sea, drink the wild air.

What you do speaks so loudly that I cannot hear what you say.

Make your own Bible. Select and collect all the words and sentences that in all your readings have been to you like the blast of a trumpet.

The earth laughs in flowers.

Once you make a decision, the universe conspires to make it happen.

Life is a journey, not a destination.

Adopt the pace of nature: her secret is patience.

Cultivate the habit of being grateful for every good thing that comes to you, and to give thanks continuously. And because all things have contributed to your advancement, you should include all things in your gratitude.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of English poet, philosopher, theologian, and literary critic Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who was a co-founder of the Romantic Movement. He is considered one of the most renowned English poets and is best known for his epic poems Kubla Khan and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, both of which showcase his imaginative and lyrical style.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge was born in Devon, England in 1772. His father was a well-respected parish priest and the headmaster at a local grammar school, who had thirteen children. Coleridge was the youngest of ten children by his second wife, who was the daughter of the mayor.

Coleridge’s father provided him with early exposure to literature, and Coleridge “took no pleasure in boyish sports.” Instead, he read “incessantly” and spent time by himself. In 1778, when Coleridge was just five years old, his father passed away, and this marked the beginning of a challenging period for him. Coleridge was sent to Christ’s Hospital School in London, which was known for its rigorous academic environment. This provided Coleridge with a strong classical education, focusing on Latin, Greek, and literature, as well as providing a foundation for his philosophical pursuits.

However, Christ’s Hospital School was also emotionally challenging for Coleridge. He often felt isolated and homesick there, and this contributed to his lifelong struggles with anxiety and depression. Despite his academic success, Coleridge struggled with feelings of loneliness, which were compounded by the strict and often harsh environment of the school.

In 1791, Coleridge left Christ’s Hospital School to attend Jesus College in Cambridge, where he excelled academically. However, he struggled with financial difficulties and dissatisfaction with his studies, leading him to leave Cambridge in 1793 without a degree. During this period, Coleridge also became increasingly interested in radical political ideas, particularly those influenced by the French Revolution and the broader Enlightenment ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

After a brief enlistment in the British Army— where he struggled with the physical demands and the discipline required— in 1795, Coleridge began his career as a poet and writer. He was inspired to write poetry by his love of nature and literature, as well as his powerful emotions and imagination. In 1796, he published his first major work, Poems on Various Subjects, and he formed a close friendship with poet William Wordsworth, which led to collaborations that would define the Romantic Movement.

The Romantic Movement was literary and artistic in the late 18th and early 19th centuries that emphasized emotion, individualism, nature, and the glorification of the past and the imagination, as a reaction against the industrialization and rationalism of the Age of Enlightenment.

In 1797, Coleridge moved to Somerset, where he lived near Wordsworth, and the two poets started working together. In 1798, Coleridge and Wordsworth published Lyrical Ballads, a landmark collection that marked the beginning of the Romantic era. Between 1797 and 1798, Coleridge wrote his epic poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner — which is 620 lines long, divided into seven parts — and is about an old sailor who recounts his harrowing journey, where he faces supernatural forces after killing an albatross, ultimately learning a profound lesson about the sanctity of all living things. It was first published in 1798 as part of Lyrical Ballads.

Around this time, Coleridge’s health began to decline, and his emotional difficulties intensified, so he began relying on opium more and more for relief, which led to an addiction. Although Coleridge is believed to have started using opium in the early 1790s, primarily for medical reasons to relieve pain, his use gradually increased over the years.

Around this time, Coleridge wrote his most famous poem, Kubla Khan, although it wasn’t published until 1816. The poem describes the construction of a majestic palace by the Mongol emperor Kubla Khan in the city of Xanadu, and it masterfully blends vivid imagery of nature with supernatural elements. The poem is known for its dreamlike quality, which Coleridge attributed to an opium-induced vision. Coleridge claimed that he composed the poem in its entirety during an opium-fueled sleep, but when he awoke and began to write it down, he was interrupted, and much of the poem was forgotten, leaving it incomplete, at 54 lines long. Opium played a crucial role in inspiring the surreal and imaginative content of the poem, contributing to its mystical and otherworldly atmosphere.

In the years that followed, Coleridge’s life was marked by increasing struggles with his health and his opium addiction, which affected his personal and professional life. Nonetheless, Coleridge traveled extensively during this period, where he sometimes lectured, and he continued to write, although his productivity waned compared to earlier years. In 1804, Coleridge journeyed to Malta, where he sought to improve his health and served as Acting Public Secretary for the British government.

In 1809, Coleridge launched The Friend, a periodical that he wrote almost entirely by himself, focusing on philosophy, politics, and literature, although it was short-lived. During this time, Coleridge also delivered a series of influential lectures on Shakespeare and Milton, which helped establish his reputation as a leading literary critic. Despite these achievements, his personal life remained troubled, with his addiction worsening.

In 1815, Coleridge began living with the Gillman family in Highgate, London, where he sought treatment for his opium addiction and began working on his later philosophical works. James Gilman was a compassionate physician, who took a special interest in Coleridge’s well-being and provided him with medical supervision, as well as a stable living environment and friendship for the rest of his life.

After moving in with the Gillman family, Coleridge experienced a period of relative stability, and this was marked by a deepening of his philosophical and theological ideas. In 1816, in addition to Kubla Khan being published, he also published some of his most famous poems, including Christabel and Pains of Sleep. In 1817, he published Biographia Literaria, a major work of literary criticism and autobiography that articulated his philosophical views and literary theories. In 1825, Aids to Reflection, was published, which explored Christian philosophy and theology, and this had a lasting impact on religious thought in England. Coleridge also continued to give influential lectures on literature, religion, and philosophy.

After this, Coleridge’s health continued to decline, largely due to his opium addiction, as well as other ailments. Despite his worsening condition, he remained intellectually active, continuing to write and engage in philosophical and theological discussions. Coleridge’s influence as a literary critic and philosopher grew during this time, as his earlier works gained greater recognition. He spent these final years at the Gillman Residence in Highgate.

In 1834, Coleridge died in Middlesex, England at the age of 61. He is buried in the aisle of St. Michael’s Church in Highgate, London.

Coleridge’s work holds significant spiritual and philosophical importance due to his deep engagement with ideas about the human soul, imagination, and the nature of reality. His poetry explores themes of sin, redemption, and the interconnectedness of all living things, reflecting his spiritual concerns. Coleridge’s philosophical writings emphasize the role of the imagination as a bridge between the material and spiritual worlds, influencing later Romantic and transcendental thought.

Coleridge’s exploration of Christian theology, metaphysics, and the power of the human mind had a profound impact on both literature and philosophy, contributing to the development of idealism and influencing thinkers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and John Stuart Mill. His exploration of metaphysical and spiritual themes has influenced both literary and philosophical thought, making him a central figure in the intellectual history of the 19th century. Coleridge’s work continues to be celebrated for its depth, creativity, and profound insights into the human condition.

Some of the quotes that Samuel Taylor Coleridge is known for include:

No man was ever yet a great poet, without at the same time being a profound philosopher.

Common sense in an uncommon degree is what the world calls wisdom.

Prose: words in their best order; poetry: the best words in the best order.

Advice is like snow; the softer it falls, the longer it dwells upon, and the deeper it sinks into the mind.

Our own heart, and not other men’s opinions, forms our true honor.

He who is best prepared can best serve his moment of inspiration.

A great mind must be androgynous.

What comes from the heart goes to the heart.

No mind is thoroughly well-organized that is deficient in a sense of humor.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of American poet Walt Whitman. Although Whitman is now considered one of the most influential poets in American history, his work was controversial during his lifetime, particularly his collection Leaves of Grass, which some critics described as “obscene” because of its overt sexuality.

Walter Whitman, Jr. was born in Huntington, New York in 1819. He was the second of nine children. Both of his parents were Quakers with little education. Whitman’s father was a carpenter, and he was nicknamed “Walt” to distinguish him from his father, Walter Whitman, Sr. At the age of four, he moved to Brooklyn with his family, and they struggled economically.

Whitman generally described his childhood as being “restless and unhappy,” due to his family’s financial difficulties, but he later recalled one particularly happy moment. During a celebration in 1825 at a library in Brooklyn, the Revolutionary War hero General Marquis de Lafayette lifted the young Whitman into the air and kissed his cheek. Years later, Whitman worked at that same institution as a librarian.

Whitman attended public schools in Brooklyn up until the age of 11, after which he sought employment to assist his family. He worked as an attorney’s assistant, had clerical jobs with the federal government, and was a newspaper printer. In 1831, Whitman took a job as the apprentice of Alden Spooner, who was the editor of the weekly newspaper The Long Island Star. Whitman spent much time at his local library, he joined a town debating society and began attending theater performances.

It was around this time that Whitman published some of his earliest poetry in The New York Daily Mirror. In 1835, he worked as a typesetter in New York City, and the following year he moved back in with his family in Long Island, where he taught intermittently at various schools until 1838. Whitman wasn’t happy teaching, and he decided to start his newspaper, which he called the Long Islander. Whitman did everything for the paper; he was the reporter, publisher, editor, pressman, and distributor. He even provided home delivery. After ten months he sold the publication.

Whitman continued writing. During the 1840s, he contributed freelance fiction and poetry to various periodicals, such as Brother Jonathan magazine. In 1842, Whitman wrote a novel called Franklin Evans about the temperance movement. In 1852, he serialized a mystery novel titled Life and Adventures of Jack Engle, and in 1858, he published a self-help guide called Manly Health and Training under the pen name Mose Velsor.

In 1855, Whitman self-published the first edition of his landmark poetry book Leaves of Grass, which he had been working on for around five years. This was his magnum opus. The book was strongly endorsed by Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote a five-page letter to Whitman praising the work, which was printed in the New York Tribune, and this helped to stir up considerable interest in the book. Leaves of Grass, which was widely distributed, quickly became controversial, due to claims that some of the material in the poems was sexually offensive.

On more than one occasion, Whitman was fired or denied work because people were offended by the sexual imagery in his poetry. Although Whitman is largely considered to be gay or bisexual by biographers, his actual sexual orientation remains a mystery, and is debated. Whitman’s sexual orientation has been generally assumed based on his poetry, as he never publicly addressed this.

In 1856, the second edition of Leaves of Grass was published, with 20 additional poems. Then further revised editions were published in 1860, 1867, and five more times throughout Whitman’s life. Whitman continued to edit and revise Leaves of Grass until his death. The title of the poetry collection is an example of Whitman’s self-deprecating wordplay and humor. It’s a pun and meant to have multiple meanings. Leaves referred to the “sheets of paper in a book,” and “grass” was used to denote “things that weren’t of much value.” In other words, Leaves of Grass means “pages of little value.”

Whitman is often referred to as the “father of free verse poetry.” The poems in Leaves of Grass do not rhyme or follow standard rules for meter and length. The collection of loosely connected poems represents a celebration of Whitman’s philosophy of life, as well as his praise of nature and the human body. The first edition only contained twelve poems and the final edition contained over 400. The last version of the book was published in 1892, and is referred to as the “deathbed edition.”

Whitman’s poetry is intertwined with America’s past, and many scholars consider him to be an important figure in understanding our country’s history, because of his ability to write in a singularly American character. During the American Civil War, Whitman went to Washington, D.C. where he volunteered to work in hospitals caring for the wounded, and when President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated Whitman wrote a highly influential poem about him called O Captain! My Captain. According to poet Ezra Pound, Whitman is “America’s poet… He is America,” and Whitman said, “The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem.”

During his lifetime, groups of disciples and admirers of Whitman formed, who would meet to read and discuss his poetry. One group subsequently became known as the Bolton Whitman Fellowship, or Whitmanites” and its members held an annual Whitman Day celebration around the poet’s birthday on May 31st.

Whitman died in 1892, at the age of 72. He is buried at the Harleigh Cemetery in Camden, New Jersey.

In 1940 a U.S. postage stamp was created in Whitman’s honor. His poetry has been set to music by more than 500 composers, and his vagabond lifestyle was adopted by the Beat culture and its writers, such as Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac in the 1950s and 1960s. Here in my hometown, at the Bookshop Santa Cruz, there’s a life-size replica of Gabriel Harrison’s famous drawing of Whitman standing at the front entrance of the store as its mascot.

Some of the quotes that Walt Whitman is known for include:

Keep your face always toward the sunshine— and shadows will fall behind you.

Re-examine all you have been told. Dismiss what insults your soul… Whatever satisfies the soul is truth.

The art of art, the glory of expression, and the sunshine of the light of letters, is simplicity.

“I do not ask the wounded person how he feels, I myself become the wounded person.

Pointing to another world will never stop vice among us; shedding light over this world can alone help us.

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

I am satisfied … I see, dance, laugh, sing… I exist as I am, that is enough.

I believe a leaf of grass is no less than the journeywork of the stars.

In the faces of men and women, I see God.

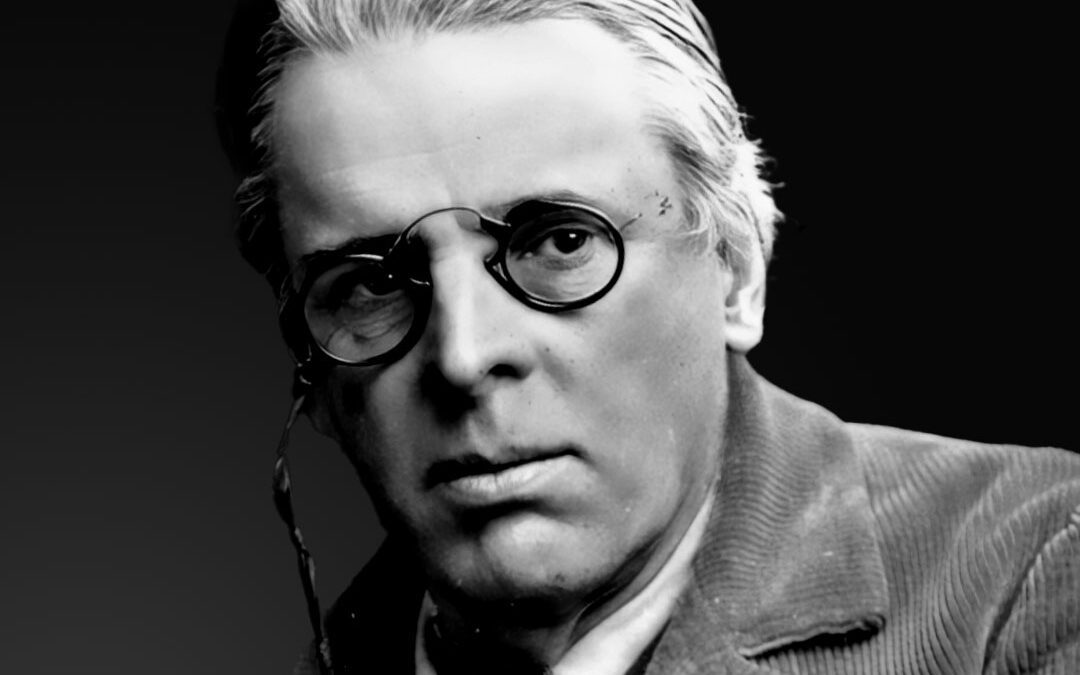

Carolyn and I have admired the work of Irish poet and playwright William Butler Yeats, who won the 1923 Nobel Prize in Literature, and whose work was inspired by his mystical experiences. Yeats was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival, a movement that renewed interest in aspects of Celtic cultures, and he co-founded the Abbey Theatre in Dublin.

William Butler Yeats was born in Sandymount, Ireland in 1865. Yeats’ mother came from a wealthy merchant background, and his family was unusually creative. Jervis Yeats, William’s great-great-grandfather, was a well-known painter, and his father, brother, and sisters, were all painters or artists. In 1867, the family moved to London to aid their father in his career as a portrait painter.

Yeats received his initial education at home, where his mother entertained him with Irish folktales. He read poetry from an early age and was fascinated by Irish legends. In 1877, Yeats entered the Godolphin School in West London, where he studied for four years. Yeats had difficulty with language because he was tone-deaf. He was also a poor speller due to dyslexia, and so was “only fair” in his academic performance.

That same year Yeats began writing his first poetry when he was seventeen. He was influenced by the work of Percy Bysshe Shelley and William Blake, and he wrote early poems about love, magicians, monks, and a woman accused of paganism.

In 1880, Yeats’ family returned to Dublin for financial reasons. Yeats resumed his education at Dublin’s Erasmus Smith High School. His father’s studio was nearby, and Yeats spent a great deal of time there, where he met many of the city’s artists and writers. In 1885, the Dublin University Review published Yeats’ first poems, as well as an essay entitled The Poetry of Sir Samuel Ferguson. Between 1884 and 1886, Yeats attended the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin.

In 1889, Yeats’ first volume of verse, The Wanderings of Oisin and Other Poems, was published. It is slow-paced lyrical poetry that tells the story of a mythical hero who embarks on a journey to the Land of Youth, and is notable for its use of vivid imagery, mythological references, and a sense of nostalgia for Ireland’s past.

Yeats had mystical experiences throughout his life, and he describes having had visionary encounters with spirits or supernatural beings since childhood. Yeats said that he had visions of a figure that appeared to be a spiritual guide and that this figure communicated with him, and provided him with insights and wisdom about life and art. Yeats was deeply interested in mysticism, the occult, and the esoteric, and these interests were reflected in his poetry and writings. For example, in the following excerpt from his poem Vacillation, Yeats describes how he felt during a mystical experience:

“While on the shop and street I gazed,

My body for a moment blazed,

And twenty minutes, more or less,

It seemed, so great my happiness,

That I was blessed and could bless.”

In 1890, Yeats joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a secret society in Great Britain devoted to the study and practice of ritual magic, the occult, metaphysics, and spiritual development, and his interest in mysticism was further informed by Hinduism, astrology, spiritualism, and theosophical beliefs. Yeats also believed in fairies, that they are real, living creatures.

The late 19th Century saw a literary movement called The Irish Literary Revival, which was a flowering of Irish creative talent in poetry, music, art, and literature. There were two main hubs, London and Dublin, and Yeats was considered a major figure in this movement. In 1888, he published Fairy and Folk Tales of Irish Peasantry, and in 1893, he published The Celtic Twilight, a collection of folklore and reminiscences from Ireland that were important to this moment.

Yeats also wrote plays. In 1903 he published On Baile’s Strand, about the Irish mythological hero Cuchulain, which was first performed at the grand opening of the Abbey Theatre in Dublin in 1904. The Abbey Theatre — which is one of Ireland’s leading cultural institutions — was co-founded in 1899 by Yeats, along with Lady Gregory and Edward Martyn. The Abbey Theatre was the first state-subsidized theatre in the English-speaking world, and the performances there played to a mainly working-class audience, rather than the usual middle-class Dublin theatergoers. Some of Yeats’ other plays included Dierdre and The King of the Great Clock Tower. In 1917, Yeats married Georgia Hyde-Less, who was 25 years younger, and they went on to have two children together. During their marriage, the couple experimented with various techniques for spirit contact, and communication with spirits, who they referred to as their “instructors.”

Yeats was politically motivated, and he was a part of the Irish Nationalist Movement that asserted that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. In 1922, Yeats was appointed Senator for the Irish Free State, and he served two terms, until 1928. His time as a senator allowed him to contribute to the cultural and political landscape of Ireland in different ways.

In 1923, Yeats was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for “his always inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation,” beating out Nietzsche’s sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche.

In 1925, Yeats published a book-length study of various philosophical, astrological, and poetic topics titled A Vision, which he wrote while experimenting with “automatic writing” with his wife, and serves as a “meditation on the relationships between imagination, history, and the occult.” This work was substantially revised by Yeats in 1937.

In 1934, Yeats received a controversial Steinach operation (a half of a vasectomy) which supposedly “rejuvenated” him for the last five years of his life. Yeats was reported to find “new vigor, evident from both his poetry and his intimate relations with younger women,” which he described as a “second puberty.”

Yeats died in 1939 in Menton, France at the age of 73. During his lifetime, Yeats published more than 100 works of poetry, drama, and prose, and was a towering figure in the world of English literature. In 1989, sculptor Rowan Gillespie created an eight-foot statue of Yeats, that now stands in front of the Ulster Bank Building on Stephen Street in Sligo, Ireland.

Some of the quotes that William Butler Yeats is known for include:

There are no strangers here; only friends you haven’t yet met.

Do not wait to strike till the iron is hot; but make it hot by striking.

Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire.

Come Fairies, take me out of this dull world, for I would ride with you upon the wind and dance upon the mountains like a flame!

Happiness is neither virtue nor pleasure, nor this thing nor that, but simply growth. We are happy when we are growing.

Think like a wise man but communicate in the language of the people.

How can we know the dancer from the dance?

What can be explained is not poetry.

If suffering brings wisdom, I would wish to be less wise.

Life is a long preparation for something that never happens.

The innocent and the beautiful have no enemy but time.

How far away the stars seem, and how far is our first kiss, and ah, how old my heart.

Take, if you must, this little bag of dreams, Unloose the cord, and they will wrap you round.

Carolyn and I have admired the work of Welsh poet, playwright, opera librettist, and biographer Peter Thabit Jones, who is the author of sixteen books, has won numerous awards for his poetry, and is regarded as an expert on the life of Dylan Thomas.

Peter Thabit Jones was born in Swansea, Wales in 1951. He was raised near Kilvey Hill, by his grandmother. His only memories of his grandfather are of him being “seriously unwell” in a bed in their parlor. Thabit Jones said that his grandfather’s nearness to death at a young age made him “really focus on life.”

Thabit Jones describes his earliest memory as being of the landscape that he could see from his home. As a toddler, he recalls looking out through the open kitchen door of his grandmother’s home and seeing Kilvey Hill, which he has described as a “huge, hulking shape” that dominated the area. As a child, Thabit Jones explored “every corner” of Kilvey Hill and the terrain of Eastside Swansea, and it was here that he developed his “pantheistic belief… that we are connected to nature.”

Thabit Jones describes Kilvey Hill as “the touchstone to that reality that, down the years, changed into memories: my first bonfire night, first gang of boys, first camping experience, first love.” In 1999 Thabit Jones published a book of poems inspired by his time there, called the The Ballad of Kilvey Hill, and in 2007 his poem Kilvey Hill was incorporated in a stained glass window, created by Welsh artist Catrin Jones, in the Saint Thomas Community School in Eastside Swansea.

As Thabit Jones grew older, he explored the busy docks nearby, the beach, and the seaside town of Swansea. He was “curious about the reality of things” and “the depth of experience.” Thabit Jones began reading the work of well-known poets, such as Wordsworth, Tennyson, R.S. Thomas, Dylan Thomas, and Ted Hughes. Reading the work of these monumental poets helped Thabit Jones to realize that he was “not alone in wanting, almost needing, to see ‘shootes of everlastingness’ beyond the curtain of reality.”

It was in 1975 that Thabit Jones began to find his own voice as a poet. Thabit Jones describes the turning point in his life as occurring after the death of his second son, Mathew, when he experienced deep personal grief.

In 1993, Thabit Jones began tutoring English literature and creative writing at Swansea University, which he continued doing until 2015.

In 1997, Thabit Jones began corresponding with New York poet, critic, and Professor Vince Clemente, who helped to inspire him, and they began sharing poems in progress. That same year, Thabit Jones visited New York University, as well as other schools and organizations in New York and New Jersey, where he gave poetry readings. In 2001, Clemente, via correspondence, introduced Thabit Jones to American publisher and poet Stanley H. Barkan, who has been a great supporter of Thabit Jones and his writings and is also Carolyn’s publisher.

In 2005, Thabit Jones founded the international poetry magazine The Seventh Quarry, which he edits to this day. In 2006, The Seventh Quarry was awarded the second best Small Press Magazine Award by Purple Patch U.K. Awards.

Thabit Jones is a recognized expert on the life of Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, who I wrote a profile about a number of months ago. In 2008, Thabit Jones embarked on a six-week Dylan Thomas Tribute Tour of America— from New York to California— with Aeronwy Thomas, daughter of Dylan Thomas. The tour was organized by Clemente and Barkan, who they shared as a publisher. It was on this trip— where they visited a number of cities across the country, lecturing, answering questions, and reading prose and poetry by Dylan Thomas— that Thabit Jones first met Carolyn, and their adventure is recounted in Thabit Jones’ commemorative book America, Aeronwy, and Me.

At the end of their tour, Thabit Jones and Thomas were commissioned by the Welsh Assembly Government in New York to write the book Dylan Thomas: Walking Tour of Greenwich Village. Their book serves as a self-guided tour of ten places in Greenwich Village, New York, associated with Dylan Thomas, and it contains a foreword by Hannah Ellis, the granddaughter of Dylan Thomas. Thabit Jones’ guided journey is also available as a smartphone app and as an escorted tour through New York Fun Tours.

In 2017, Thabit Jones published a book of his play The Fire in the Wood, which is about the life of Edmund Kara, the celebrated Big Sur sculptor that I wrote a profile about a number of months ago. That year it was performed at the Actors Studio of Newburyport in Massachusetts, and in 2018 it was performed at the Carl Cherry Center for the Arts in Carmel, California.

Thabit Jones has taught numerous writing workshops throughout Europe, does poetry readings around the world, and his poetry has been published in many magazines, literary journals, and newspapers, such as the U.K. Poetry Review, the Salzburg Poet’s Voice, and the New England Review. He is the author of sixteen books, including The Lizard Catchers, Garden of Clouds, Under the Raging Moon, A Cancer Notebook, and Poems from a Cabin in Big Sur.

Thabit Jones’ poetry has been translated into over twenty-two languages, and he is the recipient of numerous awards, including First Prize in the International Festival of Peace Poetry in 2007, the Eric Gregory Award for Poetry, The Society of Authors Award, The Royal Literary Fund Award, and the Homer European Medal for Poetry and Art.

For a number of years, Thabit Jones has spent his summers as writer-in-residence at the cabin by Carolyn’s home in Big Sur, and he is the author of The Fathomless Tides of the Heart, which is an inspiring and enthralling biography of Carolyn that was just published this year.

In an interview with Peter Thabit Jones conducted in 2009 by Kathleen O’Brien Blair, he shares some of his thoughts on how he writes his poetry, and humanity’s relationship with nature. Here are some excerpts from their conversation:

Kathleen: What is it about the little things and passing vignettes of life that catch your attention?

Peter: I think the little things are all revelations of the big things, thus when observing something like a frog or a lizard one is observing an aspect of creation, a thing that is so vital and part of the larger pattern that none of us really understand. Edward Thomas said, ‘I cannot bite the day to the core’. In each poem I write I try to get closer to the core of what is reality for me, be it the little things or the big things such as grief and loss.

Kathleen: When you write, do you write a poem and then pare it down to its bones, or do the bones come first?

Peter: For me the bones come first, a word, a phrase, a line, or a rhythm, usually initiated by an observation, an image, or a thought. Then once I have the tail of a poem I start thinking of its body. Nowadays, within a few lines, I know if it will be formal or informal. If it is formal, all my energies go into shaping it into its particular mold, a sestina, or whatever. If it is informal, I apply the same dedication. Eventually after many drafts, a poem often then needs cutting back because of too many words, lines, or ideas. R.S. indicated that the poem in the mind is never the one on the page, and there is so much truth in that comment. The actual writing of a poem for me is the best thing about being a poet: publication, if possible, is the cherry on the cake.

Kathleen: Wildness and nature always seems to overcome our best efforts to cage, encrust, or otherwise tame it. Why do you think so many people, and the modern world as a whole, think they can best it? What is it about people, do you think, that they just have to keep trying at that?

Peter: Well, man has to dominate, not just nature but each other. Man strives to be godlike and getting nature/wildness under his thumb maybe confirms that side of his ego. Maybe there is an element of envy too, the freedom of an eagle in the sky, the sheer force of a river, the dignity of a mountain. Modern man has also lost his respectful relationship with nature. Pre-literate people understood and appreciated the preciousness of the world they inhabited, that they were mere brief visitors to the Earth, protectors of it for the generations to come.