Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

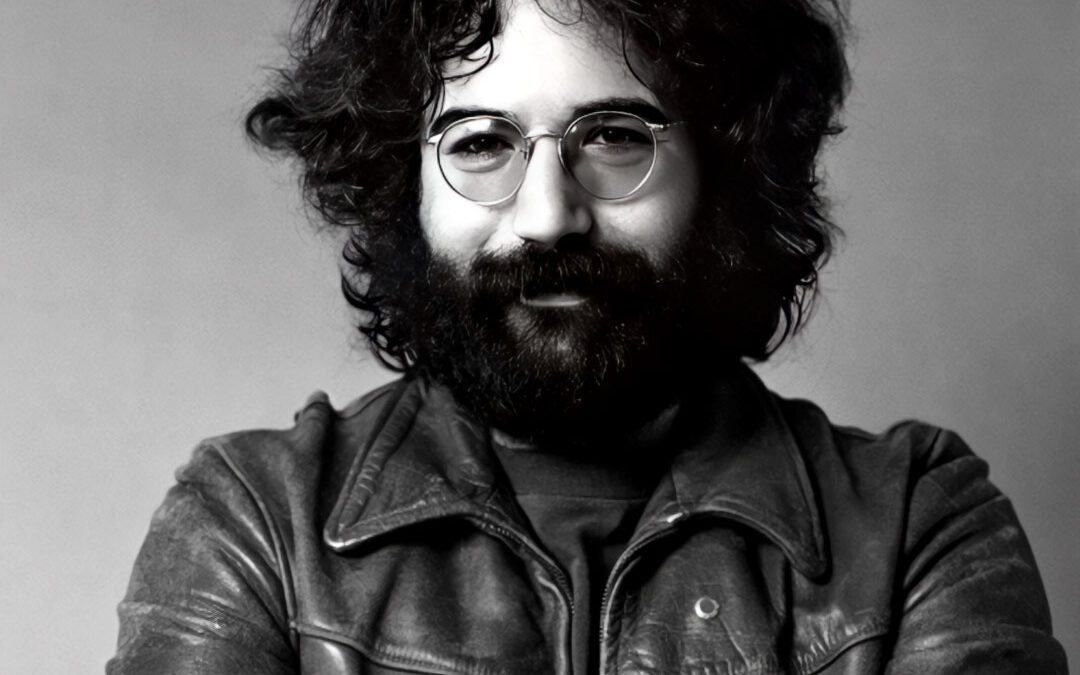

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of musician, singer, and songwriter Jerry Garcia, best known as the lead guitarist and vocalist for The Grateful Dead, one of the most influential and enduring bands in rock history. With his distinctive improvisational guitar style and eclectic musical influences— ranging from bluegrass and folk to jazz and psychedelic rock — Garcia helped pioneer the countercultural sound of the 1960s. Garcia’s live performances with The Grateful Dead became the stuff of legend, defining an era of improvisational rock and fostering an unparalleled concert experience.

Over their 30-year career, The Grateful Dead played more than 2,300 concerts, the most of any band in history at the time. Their shows drew millions of fans, with some estimates suggesting that more than 25 million people attended their concerts. Beyond The Grateful Dead Garcia collaborated on numerous side projects, including the Jerry Garcia Band, and contributed to a wide array of musical recordings. A cultural icon, Garcia’s artistry and free-spirited philosophy left an indelible mark on generations of musicians and fans.

Jerome John Garcia was born in 1942 in San Francisco, California. Both of his parents had strong ties to music and the arts. His father was a Spanish immigrant who worked as a Jazz musician and owned a tavern in San Francisco. He played woodwind instruments, particularly the clarinet and saxophone, and was part of a swing band. His mother was a native Californian who took over managing the family tavern after her husband died in 1947. She was independent and strong-willed, later working as a nurse. His mother also had a deep appreciation for music, which she passed down to Jerry, encouraging his artistic interests from a young age.

Garcia’s father drowned while fishing when Garcia was only five, leaving his mother to raise him and his older brother. That same year, Garcia suffered another life-altering event when he accidentally lost two-thirds of his right middle finger in a wood-chopping accident in the Santa Cruz Mountains, an injury that would later shape his distinctive guitar-playing style. Despite these hardships, his early years were filled with artistic and musical exposure, as his mother encouraged his creativity, and he developed an early love for the guitar.

As a child, Garcia was artistic, imaginative, and somewhat rebellious. He had a deep love for drawing and storytelling, often spending hours sketching and immersing himself in comic books and science fiction. Despite his early exposure to music, he initially showed more interest in visual arts than in playing instruments. He was also known for his mischievous streak, sometimes getting into trouble at school and struggling with authority. Garcia adapted quickly to losing part of his finger and didn’t let it hinder his creativity. His mother described him as a dreamer, and even as a young boy, he had an unconventional, free-spirited nature that foreshadowed his future as a countercultural icon.

Garcia was largely raised by his grandparents and older brother. In 1950, his mother enrolled him in an art school, nurturing his passion for drawing and creativity. However, Garcia was a restless and rebellious student, often struggling in structured environments. In 1953, at the age of 11, his mother moved the family to Menlo Park, California, where he was first introduced to rhythm and blues and early rock ‘n’ roll through the radio and his older brother’s record collection. Around this time, he also started experimenting with the banjo and guitar, marking the beginning of his lifelong relationship with stringed instruments.

In 1957, Garcia’s older brother introduced him to rock and roll, sparking his love for the electric guitar. Around this time, he discovered Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley, whose music greatly influenced his playing style. In 1959, Garcia dropped out of high school and briefly attended the San Francisco Art Institute before joining the U.S. Army— though his rebellious nature led to a discharge after just nine months. After leaving the military in 1960, he drifted through Northern California, living a bohemian lifestyle and immersing himself in folk and bluegrass music.

A major turning point came in 1961 when a near-fatal car accident left him determined to dedicate his life to music. Garcia and several friends were driving through the Santa Cruz Mountains when the driver lost control, causing the car to flip. One of his friends died in the crash, but Garcia miraculously survived. Shaken by the experience, he later described it as a “wake-up call,” realizing that he wanted to dedicate his life to playing music rather than drifting aimlessly. This pivotal moment set him on the path toward becoming one of the most legendary musicians of all time. That same year, he met Robert Hunter, his future songwriting partner, and he began performing in coffeehouses.

Garcia began playing bluegrass and folk music in the Palo Alto area, forming the band Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions with Ron “Pigpen” McKernan and Bob Weir. By 1965, inspired by the rising psychedelic movement, the group evolved into The Warlocks and was later renamed The Grateful Dead. By 1966, The Grateful Dead became central to author Ken Kesey’s legendary Acid Tests, blending psychedelic rock with improvisational jamming in environments where psychedelics were consumed.

Psychedelics played a profound role in shaping Garcia’s creativity, philosophy, and musical approach. His early experiences with LSD expanded his perception of reality and deeply influenced his improvisational style, allowing him to approach music as a fluid, ever-evolving conversation. Psychedelics also reinforced his free-spirited philosophy, emphasizing the importance of play, spontaneity, and interconnectedness, both in life and on stage. He saw The Grateful Dead performances as shared psychedelic experiences, where music became a vehicle for exploration, transformation, and collective consciousness.

As the San Francisco counterculture movement flourished, The Grateful Deadsigned with Warner Bros. Records and released their self-titled debut album in 1967. Their live performances, particularly at events like the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, solidified their reputation as pioneers of psychedelic rock. By 1968, they were expanding their musical range, incorporating jazz and experimental elements.

The Grateful Deadwas known for its extended, free-flowing jams, unpredictable setlists, and deep connection with its audience, earning a devoted fanbase known as Deadheads. The band’s ability to create a unique, ephemeral musical experience at every show made their live performances an essential part of their legacy. In 1969, Garcia and The Grateful Dead performed at Woodstock, further cementing their role in the counterculture movement. That same year, they released Live/Dead, their first live album, which captured their legendary improvisational style. In 1970, they reached new heights with the release of Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty, albums that introduced a folk and country influence, including classics like Truckin’ and Casey Jones.

Throughout the early ’70s, Garcia also explored side projects, forming the Jerry Garcia Band and collaborating with other musicians. By 1972, after the passing of founding member Pigpen, the band continued evolving musically, culminating in their 1972 European tour and live album. In 1973, they released Wake of the Flood, the first album on their independent label, Grateful Dead Records. However, in 1974, the band temporarily took a break from touring, partly due to the physical and financial toll of their massive Wall of Sound speaker system experiment. Despite this, Garcia remained musically active, releasing solo albums and continuing to refine his eclectic style before The Grateful Deadreturned in 1976.

In 1971, our friend psychologist Stanley Krippner conducted a telepathy experiment at a Grateful Dead concert at the Capitol Theatre in Port Chester, New York. The experiment aimed to test whether telepathic communication could occur between the band’s audience and a designated “receiver” in a sleep lab. While the Grateful Dead played, members of the audience were shown a series of randomly selected images on a screen and were instructed to mentally “send” these images to a sleeping subject at the Maimonides Medical Center Dream Laboratory in Brooklyn. Later, when the receiver’s dreams were analyzed, some notable correspondences emerged between the dream imagery and the projected pictures, suggesting possible extrasensory perception. Though not conclusive, the study remains one of the most fascinating intersections of parapsychology, music, and consciousness research, reflecting both Krippner’s and the Grateful Dead’s interest in mind expansion and the nature of reality.

In 1976, Garcia and The Grateful Dead resumed touring with a refined, jazz-influenced sound, and in 1977, they released Terrapin Station, featuring the epic title track that became a fan favorite. The late ’70s saw some of their most acclaimed live performances. During this period, Garcia also expanded his solo work, releasing Cats Under the Stars in 1978 with the Jerry Garcia Band, which he later called his favorite personal project. However, by the early 1980s, Garcia’s heroin addiction and declining health began affecting his performance.

In 1986, Garcia fell into a diabetic coma, nearly dying. After awakening, he had to relearn how to play the guitar, but the experience revitalized his passion for music. By 1987, The Grateful Deadexperienced an unexpected commercial breakthrough with In the Dark, which featured the song Touch of Grey, their only Top 10 hit. The album’s success introduced the band to a new generation of fans, leading to sold-out stadium tours.

The Grateful Dead remained one of the highest-grossing touring acts, playing massive stadium shows and embracing new technology, including MIDI guitars to expand their sound. Garcia also rekindled his love for acoustic music, collaborating with David Grisman on several projects. However, his health deteriorated due to diabetes, weight gain, and ongoing substance abuse. In 1992, Garcia was hospitalized and forced to take a break from touring, but he returned the following year despite continuing struggles. As his health struggles intensified, Garcia’s outlook on life and music remained deeply influenced by his spiritual philosophy, which had long been intertwined with his artistic journey.

Garcia had a fluid and open-ended spiritual perspective, shaped by psychedelics, Eastern philosophy, and the countercultural ethos of the 1960s. He was fascinated by mysticism, the nature of consciousness, and the interconnectedness of all things, often expressing a belief in cosmic playfulness and improvisation as guiding forces in life and music. Though he wasn’t formally religious, he was deeply influenced by Buddhism, the Tao Te Ching, and the transcendental aspects of Grateful Dead performances, which he saw as a kind of collective spiritual experience shared with the audience.

Garcia’s health continued to decline, but despite this, he toured with The Grateful Dead through the summer, though his performances were often frail and inconsistent. Seeking recovery, Garcia checked into the Serenity Knolls treatment center in Forest Knolls, California, in 1995. Just days after entering rehab, he passed away in his sleep from a heart attack at the age of 53.

Garcia’s legacy extends far beyond his role as The Grateful Dead’s frontman— he became a cultural icon, embodying the spirit of musical exploration and countercultural freedom. His improvisational guitar style and genre-blending approach influenced countless musicians, while his work with The Grateful Dead helped pioneer the modern jam band movement. Beyond music, he left an impact through his artwork, humanitarian efforts, and the enduring community of Deadheads who continue to celebrate his music. Even after his passing, his influence remains alive through tribute bands, festivals, and a continued appreciation for his visionary approach to sound and storytelling.

The Grateful Dead released a total of 13 studio albums and 10 live albums during their active years, along with numerous archival releases after Garcia’s passing. While their studio albums were well-received, it was their live recordings that truly captured the essence of their improvisational spirit and kept their fanbase engaged. Commercially, The Grateful Dead achieved gold and platinum status multiple times, and the band’s total album sales exceeded 35 million worldwide.

I attended two live Grateful Dead shows in the late 1980s, and one performance of the Jerry Garcia Band. In 1993, Jerry wrote a quote for the back cover of my book Mavericks of the Mind (which was recently published in its third edition and contains an interview with Carolyn). In 1994, I interviewed Jerry for my book Voices from the Edge. It was an amazing experience for Rebecca Novick and me to have 3 hours alone with Jerry after we overheard his publicist turning down an interview with Rolling Stone magazine because he was too busy. I see our interview referenced in many books about Jerry because I think we were among the few interviewers to ask him questions outside of music, like about his near-death experience, God, psychic phenomena, and synchronicity. Here are some excerpts from our conversation:

David: Joseph Campbell, the renowned mythologist, attended a number of your shows. What was his take?

Jerry: He loved it. For him, it was the bliss he’d been looking for. “This is the antidote to the atom bomb,” he said at one time.

David: He also described it as a modern-day shamanic ritual, and I’m wondering what your thoughts are about the association between music, consciousness, and shamanism.

Jerry: If you can call drumming music, music has always been a part of it. It’s one of the things that music can do— it can transport. That’s what music should do at its best— it should be a transforming experience. The finest, the highest, the best music has that quality of transporting you to other levels of consciousness.

David: I’m curious about how psychedelics influenced not only your music but your whole philosophy of life.

Jerry: Psychedelics were probably the single most significant experience in my life. Otherwise, I think I would be going along believing that this visible reality here is all that there is. Psychedelics didn’t give me any answers. What I have are a lot of questions. One thing I’m certain of; the mind is incredible and there are levels of organizations of consciousness that are way beyond what people are fooling with in day-to-day reality.

David: How did psychedelics influence your music before and after?

Jerry: Phew! I can’t answer that. There was a me before psychedelics and a me after psychedelics, that’s the best I can say. I can’t say that it affected the music specifically, it affected the whole me. The problem of playing music is essentially of muscular development and that is something you have to put in the hours to achieve no matter what. There isn’t something that strikes you and suddenly you can play music.

David: You’re talking about learning the technique, but what about the inspiration behind the technique?

Jerry: I think that psychedelics was part of music for me in so far as I’m a person who was looking for something and psychedelics and music are both part of what I was looking for. They fit together, although one didn’t cause the other.

David: What’s your concept of God if you have one?

Jerry: I was raised a Catholic so it’s very hard for me to get out of that way of thinking. Fundamentally I’m a Christian in that I believe that to love your enemy is a good idea somehow. Also, I feel that I’m enclosed within a Christian framework so huge that I don’t believe it’s possible to escape it, it’s so much a part of the Western point of view. So I admit it, and I also believe that real Christianity is okay. I just don’t like the exclusivity clause. But as far as God goes, I think that there is a higher order of intelligence something along the lines of whatever it is that makes the DNA work. Whatever it is that keeps our bodies functioning and our cells changing, the organizing principle— whatever it is that created all these wonderful life forms that we’re surrounded by in its incredible detail.

There’s a huge vast wisdom of some kind at work here. Whether it’s personal— whether there’s a point of view in there, or whether we’re the point of view, I think is up for discussion. I don’t believe in a supernatural being…. I’ve been spoken to by a higher order of intelligence— I thought it was God. It was a very personal God in that it had the same sense of humor that I have. I interpret that as being the next level of consciousness, but maybe there’s a hierarchical set of consciousnesses. My experience is that there is one smarter than me, that can talk to me, and there’s also the biological one that I spoke about.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of Lebanese-American writer, poet, visual artist, and philosopher Khalil Gibran, who is best known as the author of The Prophet — a collection of poetic essays on life, love, and spirituality— which is one of the best-selling books of all time and has been translated into more than 100 languages. Gibran’s writings, influenced by Sufi Mysticism, Romanticism, and his Lebanese heritage, emphasize universal themes of love, freedom, and self-discovery. Beyond literature, Gibran was also a talented visual artist, producing hundreds of paintings and drawings. His work bridges Eastern and Western philosophical traditions, making him one of the most celebrated poets of the 20th century.

Gibran Khalil Gibran was born in 1883 in Bsharri, a village of Ottoman-ruled Lebanon (then part of Greater Syria) to a Maronite Christian family. His father worked as a tax collector for the Ottoman authorities. His mother came from a respected family and was a strong, resourceful woman. To support her children, she worked as a seamstress. Her influence was profound, encouraging Gibran’s artistic and intellectual development while ensuring the family’s survival during difficult times.

Gibran grew up in a mountainous village rich in natural beauty, folklore, and religious influences, which would later shape his poetic and mystical sensibilities. Despite hardships, these early years exposed him to Lebanon’s rich cultural traditions and spiritual heritage, which deeply influenced his later work. As a child, Gibran was introspective, imaginative, and deeply sensitive to the world around him. Despite receiving little formal education in his early years, he showed a natural talent for drawing and storytelling.

In 1891, Gibran’s father was imprisoned for financial misconduct. This event led to the Ottoman authorities seizing the family’s property, contributing to their financial struggles. This left Gibran, his mother, and his siblings struggling to survive. In 1894, his father was released, but by then, his mother had decided to seek a better life elsewhere. In 1895, she emigrated with Gibran and his siblings to the United States, settling in Boston, where they joined a thriving Lebanese immigrant community. This move was pivotal, as it exposed Gibran to Western art and literature, shaping his future as a writer and artist.

In Boston Gibran’s artistic and intellectual talents began to flourish, and he was discovered by art patron Fred Holland Day, who encouraged his creative pursuits. In 1898, Gibran’s mother sent him back to Lebanon to study at the prestigious Collège de la Sagesse in Beirut, where he deepened his knowledge of Arabic literature, poetry, and philosophy. He returned to Boston in 1902, only to face personal tragedy— his mother, sister, and half-brother all fell ill, and both his half-brother and one sister died from tuberculosis within months. In 1903, Gibran’s mother also died of tuberculosis, leaving him devastated but determined to pursue his creative dreams.

Only Gibran’s sister Mariana and he survived. Mariana became a seamstress to help support them while Gibran pursued his artistic and literary career. These losses profoundly impacted Gibran’s outlook, reinforcing themes of love, loss, and spirituality in his later work. He found support from Mary Haskell, a school principal who became his patron, editor, and close confidante. With her financial help, he traveled to Paris in 1908 to study art at the Académie Julian, where he was exposed to European artistic movements and met influential intellectuals. During this time, he refined his artistic and literary vision, blending Eastern mysticism with Western artistic techniques — an approach that would define his later works.

In 1910. Gibran returned to the United States and settled in New York, where he established himself in the artistic and literary circles of the city. Supported by Haskell, he focused on developing his English-language writing, shifting from Arabic to a broader audience. During this period, he published several works in Arabic, including Broken Wings in 1912, a novel exploring love and societal constraints. As World War I unfolded, he increasingly advocated for Syrian and Lebanese independence from Ottoman rule. His engagement with politics, spirituality, and literature deepened, setting the stage for his later masterpieces.

The same year that Broken Wings was published, Gibran fell deeply in love with a Lebanese woman named May Ziadeh, a writer and intellectual living in Egypt. Though they never met in person, their passionate correspondence lasted nearly 20 years, filled with poetic exchanges about love, art, and philosophy. Their letters reveal a profound emotional and intellectual connection, making it one of the most famous literary romances conducted entirely through writing. Despite their mutual affection, they never bridged the physical distance, leaving their love story forever in the realm of words and longing.

Gibran’s early works were sketches, short stories, poems, and prose poems written in simple language for Arabic newspapers in the United States. In 1918, Gibran published The Madman, his first book in English, marking a turning point in his literary career. Over the next few years, he continued writing and painting, refining his distinctive blend of mysticism, philosophy, and poetic prose.

Gibran’s spiritual perspective was deeply mystical, blending elements of Christianity, Sufism, and Eastern philosophy. He saw love as the highest spiritual force and believed in the unity of all existence, often emphasizing the interconnectedness of humanity with the divine. His work rejects rigid dogma and instead embraces a personal, experiential approach to spirituality, valuing inner wisdom, freedom, and self-discovery. Gibran’s vision of God was not confined to religious institutions but found in nature, art, and human relationships. His writings encourage transcendence beyond materialism and ego, advocating for a life guided by love, beauty, and compassion.

Gibran became a leader among the Lebanese and Syrian immigrant intellectual community in New York, advocating for the independence of his homeland from Ottoman and later French rule. During this period, he worked on what would become his most famous book, The Prophet, which he completed in 1922, and contains his illustrations. Gibran’s growing influence positioned him as a visionary thinker bridging Eastern and Western traditions.

In the following years, Gibran reached the height of his literary fame. In 1923, he published The Prophet, his masterpiece, which received modest initial success but gradually became one of the most beloved and widely translated books of all time. The book’s poetic meditations on love, freedom, and the human condition cemented his reputation as a visionary writer. During these years, Gibran continued to write and paint. In 1928, he published Jesus, The Son of Man, a unique retelling of Christ’s life through the voices of those who knew him. However, his health began to decline due to chronic illness and years of excessive alcohol consumption.

Gibran’s health deteriorated due to chronic liver disease and tuberculosis. Despite his declining condition, he continued working on his writings and artistic projects. In 1931, Gibran passed away in New York City at the age of 48. As per his wishes, his body was transported back to his birthplace, Bsharri, Lebanon, where he was buried in a monastery that later became a museum dedicated to his life and work.

The Gibran Museum is housed in what was an old cavern, known as the Monastery of Mar Sarkis, where many hermits sought refuge since the 7th century. Founded in 1935, the Gibran Museum possesses 440 original paintings and drawings by Gibran and his tomb. It also includes his furniture and belongings from his studio when he lived in New York City and his private manuscripts.

Though he died relatively young, Gibran’s legacy as a timeless poet, philosopher, and artist, whose work bridges Eastern and Western traditions, endured, with The Prophet continuing to inspire millions worldwide. It remains one of the best-selling spiritual works of all time, inspiring readers with its poetic wisdom on love, freedom, and self-discovery. Beyond his literary contributions, Gibran’s advocacy for Lebanese and Syrian independence and his philosophical explorations of human nature continue to resonate. His influence extends to writers, artists, and thinkers across cultures, solidifying his place as one of the most profound and enduring voices of the 20th century.

Some of the quotes that Khalil Gibran is known for include:

Love possesses not, nor would it be possessed; For love is sufficient unto love. And think not you can direct the course of love, if it finds you worthy, directs your course. Love has no other desire but to fulfill itself.

If you love somebody, let them go, for if they return, they were always yours. If they don’t, they never were.

Trees are poems the earth writes upon the sky, We fell them down and turn them into paper, That we may record our emptiness.

Your children are not your children.

They are sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself.

They come through you but not from you.

And though they are with you yet they belong not to you.

You talk when you cease to be at peace with your thoughts.

Some of you say, “Joy is greater than sorrow,” and others say, “Nay, sorrow is the greater.

But I say unto you, they are inseparable.

Together they come, and when one sits alone with you at your board, remember that the other is asleep upon your bed.

We are all like the bright moon, we still have our darker side.

Generosity is giving more than you can, and pride is taking less than you need.

I have found both freedom and safety in my madness; the freedom of loneliness and the safety from being understood, for those who understand us enslave something in us.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of French novelist, literary critic, and essayist Marcel Proust, considered one of the most influential authors of the 20th century. Proust is best known for his monumental seven-volume novel In Search of Lost Time, which explores memory, time, and consciousness with unparalleled psychological depth and literary innovation. Drawing on his own life and experiences, Proust pioneered a deeply introspective and impressionistic style that influenced modern literature. He is now regarded as one of the greatest novels ever written, shaping the modernist movement and inspiring generations of writers.

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust was born in 1871 in Auteuil, a wealthy suburb of Paris. His father was a distinguished physician and epidemiologist, known for his work on hygiene and public health. He played a key role in developing measures to combat infectious diseases, particularly cholera, and was a respected authority on preventive medicine. Proust’s mother came from a wealthy and cultured Jewish family and was highly educated, fluent in multiple languages, and deeply interested in literature and the arts. She maintained a close and affectionate relationship with her son, encouraging his intellectual development and sharing his literary passions. While his father embodied the scientific rationalism of the era, his mother provided the emotional and cultural foundation that deeply influenced Proust’s literary sensibilities.

As a child, Proust was sensitive, intelligent, and deeply affectionate, but he was also frail due to his chronic asthma, which often kept him indoors and under the watchful care of his devoted mother. He had a vivid imagination and an early appreciation for literature, influenced by the refined, intellectual environment of his home. Though he enjoyed moments of sociability, particularly among his family and friends, his delicate health made him introspective, and he found solace in books, nature, and his inner world.

Despite Proust’s fragile health, he demonstrated exceptional intelligence and a precocious love for literature. In 1880, at the age of nine, he began attending the Lycée Condorcet, one of Paris’s most prestigious schools, where he excelled in literature and philosophy, and also developed friendships that would later influence his writing. He became part of an elite social circle, forming friendships with well-connected classmates, which introduced him to the aristocratic and artistic milieus that would later inspire characters in his novel In Search of Lost Time. During this time, he spent idyllic summers in Illiers, a village in north-central France, where he absorbed the sensory impressions and emotional nuances that would also later be immortalized in the novel.

In 1889, Proust began his mandatory military service in Orléans, but due to his poor health, he served for only a year before being discharged. That same year, he enrolled at the Sorbonne (then the University of Paris) to study law, philosophy, and literature, though his true passion lay in literature. These formative years deepened his fascination with high society and the arts, shaping his literary ambitions and setting the stage for his future writing. Proust immersed himself in Parisian intellectual and social life while continuing his studies at the Sorbonne. He became deeply involved in Parisian salons, mingling with aristocrats, writers, and artists.

In 1896, Proust published his first book, Pleasures and Days, a collection of essays and short stories showcasing his refined prose and keen psychological insight, though it received a lukewarm reception. During this period, he also began work on Jean Santeuil, an early autobiographical novel that remained unfinished but foreshadowed the themes of his later work. He also translated and wrote a preface for Sesame and Lilies by John Ruskin, whose ideas on art and memory profoundly influenced his literary vision.

In 1903, Proust attended a high-society ball hosted by the Comtesse de Chevigné, a woman who partially inspired the character of the Duchesse de Guermantes in In Search of Lost Time. Proust, known for his keen social observations, was so captivated by the event that he later wrote a detailed letter describing every nuance of the guests’ attire, mannerisms, and conversations. However, when the Comtesse read his account, she was offended by his sharp, almost microscopic attention to detail and reportedly banned him from future gatherings. This incident highlighted Proust’s dual role as both an insider and an outsider in aristocratic circles — immersed in their world yet ultimately destined to transform it into literature.

That same year Proust experienced the devastating loss of his father, followed by the death of his beloved mother in 1905 — an event that deeply shattered him and led to a period of intense grief, deep mourning, and seclusion. Proust became increasingly isolated, and this period of loss and transformation set the stage for the creation of In Search of Lost Time, as he began retreating into the world of memory and literature. As Proust withdrew further into solitude, his reflections on memory and loss took on a near-mystical quality, shaping not only his literary ambitions but also his broader philosophical and spiritual outlook.

Proust’s spiritual perspective was deeply personal and complex, shaped by his literary vision rather than adherence to any formal religious doctrine. Raised in a household with a Catholic father and a Jewish mother, he did not practice organized religion but was profoundly interested in memory, time, and transcendence. His work suggests a belief in the transformative power of art and memory, portraying them as vehicles for capturing lost time and achieving a form of immortality. Through involuntary memory — instances in which memories come to mind spontaneously, unintentionally, automatically, and without effort — Proust conveyed a mystical sense of revelation, where past and present merge in a timeless continuum. Rather than seeking meaning in religious faith, he found it in human experience, love, beauty, and the redemptive power of literature.

After Proust’s mother passed away, he inherited a substantial fortune, allowing him to focus entirely on his writing. Around 1907, he withdrew from social life almost entirely, spending much of his time in a cork-lined bedroom to shield himself from noise and focus on his work. Solitude and quiet were essential to Proust’s creative process, allowing him to immerse himself fully in the intricate world of memory and introspection. This isolation enabled him to explore the depths of human consciousness, crafting his intricate sentences and psychological insights without distraction. Proust saw solitude not as loneliness but as a necessary state for artistic and intellectual revelation, where he could distill fleeting experiences into timeless literary expression.

During this period, Proust abandoned his earlier novel Jean Santeuil and began developing the ideas that would become In Search of Lost Time. By 1910, he had completed early drafts of key sections, refining his distinctive literary style, which blended memory, introspection, and psychological depth. His health continued to decline, but his creative ambition surged, laying the foundation for his literary masterpiece.

Proust worked intensively on In Search of Lost Time, refining its structure and style. In 1913, the first volume, Swann’s Way, was published at his own expense after being rejected by multiple publishers, including André Gide at Nouvelle Revue Française, who later regretted the decision. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 disrupted his work, and Proust largely withdrew from Parisian society, focusing on expanding his novel. Despite his worsening health, he tirelessly revised and dictated new sections, infusing the work with reflections on time, memory, and the nature of human experience. By 1917, he had completed substantial portions of the later volumes, even as his asthma and increasing physical frailty forced him into near-total seclusion.

In 1919, In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower, the second volume of the novel was published and won the prestigious Prix Goncourt, bringing Proust long-overdue literary recognition. The award, France’s most prestigious literary prize, was expected to go to Roland Dorgelès for his war novel Wooden Crosses, which chronicled the harrowing experiences of World War I soldiers. Proust’s victory sparked controversy, as critics and war veterans felt that an aristocratic writer who had spent the war in bed revisiting his memories should not have triumphed over a firsthand account of the trenches. Despite the backlash, the award cemented Proust’s reputation and helped bring his work the recognition it deserved.

Encouraged by this success, Proust continued revising and preparing the remaining volumes for publication, often dictating edits from his cork-lined bedroom. His health continued to deteriorate, but he remained intensely focused on his work, determined to complete his magnum opus. By 1921, Proust had completed drafts of all seven volumes, though only a few were published in his lifetime. In the final year of his life, Proust worked relentlessly to complete In Search of Lost Time, despite his rapidly failing health. He made final revisions to Sodom and Gomorrah, which was published that year, and continued editing the later volumes, determined to see his masterpiece through to completion.

Proust’s chronic asthma worsened, and he became confined to his bed, suffering from pneumonia and exhaustion. In 1922, Proust passed away in his Paris apartment at the age of 51. Though he did not live to see the full publication of his work, his remaining volumes were posthumously published.

Proust’s legacy is that of one of the greatest novelists of all time, who revolutionized literature with his profound exploration of memory, time, and human consciousness. Proust’s pioneering use of introspective narration, psychological depth, and intricate, flowing prose influenced countless writers, including Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Samuel Beckett. His concept of involuntary memory became a cornerstone of modernist literature and continues to shape philosophical and literary discussions. Though largely unrecognized during his lifetime, Proust’s work is now regarded as a towering achievement, inspiring scholars, writers, and readers to explore the intricate landscapes of personal and collective memory.

Some of the quotes that Marcel Proust is known for include:

Let us be grateful to the people who make us happy; they are the charming gardeners who make our souls blossom.

The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.

Always try to keep a patch of sky above your life.

Remembrance of things past is not necessarily the remembrance of things as they were.

Every reader, as he reads, is actually the reader of himself. The writer’s work is only a kind of optical instrument he provides the reader so he can discern what he might never have seen in himself without this book. The reader’s recognition in himself of what the book says is the proof of the book’s truth.

My destination is no longer a place, rather a new way of seeing.

Thanks to art, instead of seeing one world only, our own, we see that world multiply itself and we have at our disposal as many worlds as there are original artists, worlds more different one from the other than those which revolve in infinite space, worlds which, centuries after the extinction of the fire from which their light first emanated, whether it is called Rembrandt or Vermeer, send us still each one its special radiance.

Desire makes everything blossom; possession makes everything wither and fade.

We don’t receive wisdom; we must discover it for ourselves after a journey that no one can take for us or spare us.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of English playwright, poet, and actor William Shakespeare, who is widely recognized as the greatest writer in the English language. His plays, including Hamlet, Macbeth, Romeo and Juliet, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, are celebrated for their profound exploration of human nature, innovative use of language, and enduring themes of love, power, betrayal, and redemption. Shakespeare’s contributions shaped modern drama and literature, and his plays continue to be performed worldwide, making him a central figure in Western culture and a timeless literary icon.

William Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England in 1564. His father was a glove-maker and leatherworker who also held civic positions in Stratford-upon-Avon, including alderman and bailiff, the town’s highest office. Shakespeare’s mother came from a prominent, wealthy family and brought valuable land and status to the marriage. Together, they managed a household that blended skilled craftsmanship, community engagement, and ties to the local gentry, providing Shakespeare with a stable upbringing and exposure to both working-class and upper-class life.

Shortly after Shakespeare’s birth, a plague struck Stratford-upon-Avon, killing many infants, but Shakespeare survived. He likely spent his early years in the family home, surrounded by his seven siblings, though only four survived to adulthood. As the son of a prosperous family, he would have been exposed to rural life, local folklore, church teachings, the vibrant market culture of his town, and possibly early schooling by the age of five. Shakespeare attended the local grammar school, King’s New School, where he studied Latin, classical literature, and rhetoric. Though little is known about his personality, his early environment nurtured a vivid imagination and a deep understanding of human nature.

Shakespeare’s family experienced fluctuating fortunes during this time, with his father facing financial difficulties and losing some of his civic positions. Despite these challenges, Shakespeare’s exposure to the vibrant cultural and theatrical influences in Stratford-upon-Avon and nearby towns likely began to shape his imagination and interest in storytelling. Around 1582, at age 18, Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway, a farmer’s daughter eight years his senior, and they soon welcomed their first child, Susanna, in 1583.

In 1585, Shakespeare and Hathaway welcomed twins, completing their family. Shortly after this, Shakespeare’s activities become unclear, with this period often referred to as the “lost years.” Speculation suggests he may have worked as a schoolteacher, actor, or apprentice to a tradesperson, or traveled to London. By 1590, Shakespeare had likely begun establishing connections in London’s theater world, marking the early stages of his literary and dramatic career, though concrete details remain elusive.

Around this time Shakespeare began rising to prominence as a playwright and poet in London. By 1592, he was gaining recognition, though he faced criticism from other playwrights, like one who called him an “upstart crow.” During this time, Shakespeare wrote early plays like Henry VI and Titus Andronicus which were performed by acting companies such as the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. In 1593 and 1594, as theaters closed due to the plague, he published narrative poems, such as Venus and Adonis, which gained acclaim. By 1597, Shakespeare had written popular plays, including Romeo and Juliet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and had he begun purchasing property in Stratford-upon-Avon, signaling his growing financial success.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, my favorite of Shakespeare’s plays, is a whimsical comedy that intertwines the romantic misadventures of lovers, the comedic follies of amateur actors, and the magical interventions of mischievous fairies in an enchanted forest. Its dreamlike quality, surreal imagery, and exploration of altered perceptions of reality suggest inspiration from visionary states of consciousness, possibly reflecting Shakespeare’s imaginative engagement with mystical or otherworldly experiences.

Evidence suggesting Shakespeare may have used cannabis and other mind-altering herbs comes from chemical analyses conducted on clay pipe fragments excavated from his Stratford-upon-Avon garden. A 2001 study found residues of cannabis and traces of other psychoactive substances, such as coca leaf, in the pipes. While it is speculative, if Shakespeare used these substances, they may have enhanced his creativity, inspired his vivid imagination, and contributed to the rich metaphorical language and complex psychological insights in his works.

By 1598, Shakespeare was praised by contemporaries like Francis Meres for his comedies and tragedies, including The Merchant of Venice and Much Ado About Nothing. In 1599, he became a shareholder in the newly built Globe Theatre, which was a major milestone in his career. During this period, Shakespeare wrote iconic works like Julius Caesar, Hamlet, and As You Like It. In 1603, The Lord Chamberlain’s Men became The King’s Men under King James I’s patronage, further elevating Shakespeare’s status. In 1604, Shakespeare wrote Othello, which showcased his mastery of tragedy and deepening his influence on English drama.

Around this time, Shakespeare reached the height of his career, producing some of his greatest tragedies and late comedies. During this period, he wrote masterpieces like King Lear, Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, and Coriolanus, exhibiting his profound exploration of human nature and complex themes. Shakespeare’s financial success allowed him to invest in property, including the purchase of the Blackfriars Gatehouse in London in 1608. The King’s Men also began performing more frequently at the Blackfriars Theatre, an indoor venue that attracted elite audiences.

In 1610, Shakespeare began to withdraw from the London theater scene and spent more time in Stratford-upon-Avon. In 1611, Shakespeare wrote his final solo play, The Tempest, which is often seen as a reflection on creativity and legacy. The Tempest is a tale of magic, revenge, forgiveness, and reconciliation, centered on the exiled sorcerer Prospero, who uses his powers to orchestrate a shipwreck and ultimately restore harmony to those stranded on his enchanted island. Shakespeare portrays a wide spectrum of spiritual questions in his plays, from mercy and forgiveness in The Tempest to divine justice in Hamlet.

Shakespeare’s spiritual perspective is often inferred from his works, as he left no explicit writings about his personal beliefs. His plays and sonnets reflect a deep engagement with themes of morality, redemption, fate, and the afterlife, drawing from Christian doctrine and classical ideas. Shakespeare’s works suggest a profound curiosity about the human soul and its place in the cosmos, blending reverence for divine mysteries with an exploration of human agency and frailty. His nuanced treatment of spirituality reveals a universal and timeless inquiry into the sacred and the existential.

In 1612, Shakespeare collaborated on several later works, including Henry VIII and The Two Noble Kinsmen. In 1613, during a performance of Henry VIII, a cannon was fired as part of the production’s special effects, igniting the thatched roof and causing the theater to burn to the ground. Remarkably, no one was injured, and the theater was quickly rebuilt in the following year. This dramatic event highlights the risks and spectacle of Elizabethan theater. By the end of that year, Shakespeare retired from active playwriting, focusing on managing his investments, such as his substantial properties in Stratford-upon-Avon.

In the final year of his life, Shakespeare lived in Stratford-upon-Avon, where he enjoyed a comfortable retirement. He revised his will in March, making provisions for his family and leaving his “second-best bed” to his wife, a detail that has sparked much speculation. In 1616, Shakespeare passed away, at the age of 52, leaving behind an unparalleled literary legacy. He was buried in the chancel of Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon, where his grave is marked with a stone bearing a warning against moving his bones, ensuring his eternal rest.

Shakespeare’s legacy is unmatched in the history of literature and drama. He authored 39 plays, 154 sonnets, and two long narrative poems. (Although some have questioned whether Shakespeare authored all the works attributed to him, the overwhelming consensus among scholars is that he wrote them, supported by substantial historical and textual evidence.) Shakespeare’s works have profoundly influenced the English language, introducing countless words, phrases, and expressions still in use today. His exploration of universal themes—love, power, ambition, betrayal, and the human condition — has made his works timeless, resonating across cultures and generations. Shakespeare’s plays are performed more frequently than those of any other playwright, and his influence extends beyond literature to art, music, film, and philosophy. His genius continues to shape how we understand storytelling, language, and humanity itself.

Some of the quotes that William Shakespeare is known for include:

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

Love all, trust a few, do wrong to none.

What’s in a name? A rose by any name would smell as sweet

To die, to sleep;

To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub:

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come…

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

And by opposing end them.

The fool doth think he is wise, but the wise man knows himself to be a fool.

Be not afraid of greatness. Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and others have greatness thrust upon them.

There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of English writer John Milton, who is considered one of history’s greatest poets. Milton is best known for his epic poem Paradise Lost, which masterfully explores the biblical story of humanity’s fall from grace, combining profound theological insights with extraordinary poetic artistry— and is considered one of the greatest works in the English language.

Beyond his literary achievements, Milton was a staunch advocate for individual liberty, free speech, and press freedom. Despite going blind in midlife, he continued to write, dictating his later works, and he remains celebrated as one of the most influential English poets and thinkers of all time. According to some scholars, Milton is second in influence only to William Shakespeare.

John Milton was born in 1608 in London, England, into a prosperous and educated family. His father was a scrivener, which involved drafting legal documents and providing financial services. He was also an accomplished composer of church music, contributing to Milton’s early exposure to the arts. His mother managed the household and cared for the family, offering a stable and nurturing environment. His family’s financial stability and commitment to education provided the foundation for his later achievements.

As a child, Milton was precocious, highly intelligent, and deeply curious. He received a privileged early education, learning Latin and Greek, and he displayed exceptional intellectual promise as a child, particularly excelling in languages. His father’s encouragement and access to a private tutor fostered his intellectual development. Known for his discipline and dedication to study, Milton often stayed up late reading by candlelight.

Milton attended St. Paul’s School in London, where he received a rigorous classical education, studying the foundations of rhetoric and poetry. Milton’s intellectual brilliance became evident as he immersed himself in literature and language, preparing for a scholarly life. These formative years also saw his deepening interest in religion and the arts, largely influenced by his father’s musical talents and Puritan faith, which would later shape his literary voice and worldview.

In 1625, Milton enrolled at Christ’s College, University of Cambridge. During this period, he began developing his poetic talents, and writing his earliest known works. Though he briefly faced disciplinary action and was temporarily suspended from Christ’s College in 1626 due to a dispute with his tutor, Milton returned to complete his studies.

In 1629, Milton completed his Bachelor of Arts degree, and in 1632 his Master of Arts at Christ’s College, further honing his linguistic and poetic skills. During this time, Milton wrote several significant early poems, including On Shakespeare in 1630, which reflected his admiration for the Bard, and On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity in 1629. After leaving Cambridge, Milton returned to his family’s home in Hammersmith and later moved to Horton, where he devoted himself to rigorous private study of classical and contemporary works.

In 1634, his masque Comus was performed at Ludlow Castle, showcasing his mastery of dramatic poetry and themes of virtue and morality. In 1637, he wrote the pastoral elegy Lycidas in memory of a Cambridge friend, which became one of his most celebrated works. Between 1638 and 1639, Milton embarked on a transformative journey across Europe, meeting intellectuals in Italy and deepening his understanding of art, philosophy, and politics.

While visiting Florence during his travels in Italy, Milton met the renowned scientist Galileo Galilei, who was under house arrest by the Inquisition for his heliocentric views — meaning that he believed that the earth and planets orbited the sun, which contradicted the church’s prevailing view of geocentrism, which placed the earth at the center of the universe. This meeting left a profound impression on Milton, and he later referred to Galileo in Paradise Lost as the “Tuscan artist” observing the heavens through his telescope. The encounter highlights Milton’s admiration for intellectual courage and scientific inquiry, themes that permeated his works.

Around this time Milton became deeply involved in political and religious debates, setting aside poetry to write a series of influential prose works. He published tracts advocating for religious reform, such as Of Reformation in 1641 and The Reason of Church-Government in 1642, aligning himself with Puritan ideals. In 1643, Milton married Mary Powell, but the marriage was temporary, and she returned to her family, prompting Milton to write treatises advocating for divorce rights, including The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce. During this period, Milton also became a teacher, running a small school for his nephews and other students.

In 1651, as the English Civil War concluded and the monarchy was overthrown, Milton became a staunch supporter of the Commonwealth, a political community founded for the common good. In 1649, he was appointed Secretary for Foreign Tongues to the Council of State, serving as a propagandist for the new government and writing defenses of republicanism, including The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates. During this time, he penned his famous works defending the execution of King Charles I and refuting royalist arguments.

Around this time, Milton’s health started to deteriorate, and by 1652, he became completely blind, likely due to glaucoma or retinal detachment, conditions exacerbated by his intense study habits and the strain of writing and reading late into the night. Despite this, Milton continued his intellectual pursuits, dictating his writings and laying the groundwork for his later masterpieces. In 1659, Milton dictated A Treatise of Civil Power, advocating for religious liberty.

The restoration of the monarchy in 1660 marked a dangerous period for Milton as a prominent supporter of the Commonwealth. He was briefly imprisoned but later pardoned. During this time, Milton faced further personal losses, including the death of his second wife and their infant daughter.

Living a relatively quiet life in London, Milton dictated Paradise Lost, his epic masterpiece, which was published in 1667 to critical acclaim. Paradise Lost recounts the biblical story of humanity’s fall, exploring the rebellion of Satan, the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden, and themes of free will, redemption, and divine justice. The poem solidified Milton’s reputation as one of the greatest poets in the English language. During this time, he also married his third wife, who supported him in his later years. Milton continued writing, beginning work on Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes, which further explored themes of faith, redemption, spiritual triumph, and human resilience.

Milton’s spiritual perspective was deeply rooted in his Christian faith, influenced by Puritanism and his belief in individual conscience. He emphasized humanity’s direct relationship with God, advocating for personal responsibility and moral choice. His works reflect his view of God as just and sovereign, yet also compassionate, and explore themes of free will, redemption, and divine grace. Milton rejected institutionalized religion, critiquing the corruption of the Church and championing religious liberty. His writings, particularly Paradise Lost, grapple with profound spiritual questions about good, evil, and humanity’s purpose within God’s divine plan.

In 1671, Milton published Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes, and the publication of these works further cemented his status as one of the greatest English poets. Despite declining health, Milton continued to write and engage in intellectual discussions. In the final year of his life, he oversaw the publication of the second edition of Paradise Lost, which included explanatory notes and a commendatory poem by Andrew Marvell, solidifying its growing reputation. Milton lived quietly in London with his third wife and continued to receive visitors and admirers.

Milton passed away peacefully in 1674, at the age of 65, leaving an unparalleled legacy as one of England’s greatest poets and thinkers. His legacy lies in his profound contributions to literature, theology, and political thought. His epic poems and political prose showcase his mastery of language, depth of thought, and commitment to liberty and individual rights. Milton’s influence extends beyond poetry, shaping discussions on freedom of speech, religion, and the human condition. His blend of artistic genius and intellectual rigor continues to inspire writers, scholars, and readers worldwide.

Milton was revered by William Blake, William Woodsworth, and many other poets and artists. Blake created several sets of illustrations for Paradise Lost. His illustrations are renowned for their vivid symbolism and dynamic compositions, capturing the epic poem’s profound themes and complex characters. Blake’s unique artistic style brought a visionary interpretation to Milton’s work, influencing subsequent generations of artists and readers.

Some of the quotes that John Milton is known for include:

The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven.

Solitude sometimes is best society.

Long is the way and hard, that out of Hell leads up to light.

Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties.

What is dark within me, illumine.

A good book is the precious life-blood of a master spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life.

Thou canst not touch the freedom of my mind.

Yet he who reigns within himself, and rules

Passions, desires, and fears, is more a king.

For books are not absolutely dead things, but do contain a potency of life in them to be as active as that soul was whose progeny they are; nay, they do preserve as in a vial the purest efficacy and extraction of that living intellect that bred them.

-Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of English writer and feminist thinker Virginia Woolf, who had a profound influence on 20th-century literature. She is best known for her groundbreaking modernist novels, which revolutionized narrative techniques through stream-of-consciousness writing and deep psychological insight, and for being an early and central member of the Bloomsbury Group, which fostered a vibrant intellectual and artistic community.

Adeline Virginia Stephen (Woolf) was born in 1882 in London, England. She grew up in a privileged and intellectually stimulating household, rich in books and ideas, although also marked by the influence of Victorian societal norms. Her father was a prominent historian, author, critic, and mountaineer. He was the first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography and an influential intellectual figure. Her mother was renowned for her work as a philanthropist, model for Pre-Raphaelite artists, and writer of essays. She devoted much of her time to caring for her family and the sick, and her work reflected a strong moral and nurturing character.

As a child, Woolf was bright, curious, emotionally sensitive, and introspective, showing early signs of her intellectual and creative potential. She had access to her father’s vast library while growing up, where she developed her love for literature. Woolf was homeschooled by her parents and spent summers in Cornwall, where the seaside setting deeply influenced her imagination.

In 1895, when Woolf was just 13, she experienced trauma from the death of her mother, who died suddenly, plunging the family into grief. Just two years later, in 1897, Woolf’s half-sister Stella, who had taken on a maternal role, also died. These losses, combined with the strict Victorian expectations of her time and the pressures of her family’s complex dynamics, profoundly impacted Woolf, shaping her personality and contributing to her lifelong struggles with mental health.

In 1901, Woolf’s father was diagnosed with cancer, adding further strain to her adolescence. These events deeply influenced the themes of loss, family dynamics, and the fragility of mental health in her later works. In 1904, Woolf’s father died, leading to another mental breakdown and the family moved to Bloomsbury. This relocation marked the beginning of Virginia’s involvement in the Bloomsbury Group, an influential circle of writers, artists, and intellectuals.

Woolf became a central figure in the Bloomsbury Group, which was known for challenging Victorian norms and exploring progressive ideas in art, literature, philosophy, and politics, as well as for its avant-garde thinking and rejection of traditional conventions. The group included notable figures such as Lytton Strachey, John Maynard Keynes, and E.M. Forster. Woolf’s participation in the group profoundly influenced her intellectual development and provided a supportive network for her literary work.

Around this time, Woolf also began pursuing her literary aspirations, contributing book reviews to publications like The Guardian. She also traveled to Greece and Italy, which broadened her cultural perspectives. Despite Woolf’s ongoing struggles with mental health, these years established the foundation of her literary career and intellectual network.

In 1910, Woolf, along with other members of the Bloomsbury Group and her brother Adrian, disguised themselves as Abyssinian royals to prank the Royal Navy. They managed to gain a tour of the HMS Dreadnought, a prestigious warship, by donning costumes, fake beards, and dark makeup. Speaking in gibberish and using Latin phrases, they fooled the crew and received an official reception. The prank was widely publicized, showcasing Woolf’s playful side and her involvement in the irreverent humor of the Bloomsbury circle.

In 1912, she married Leonard Woolf, who became her lifelong partner and a key source of emotional and professional support. Together, they founded the Hogarth Press in 1915, which would later publish many of her works and other groundbreaking modernist literature. That same year Woolf completed her first novel, The Voyage Out, marking the beginning of her career as a novelist despite her ongoing struggles with mental health.

Woolf’s experience with mental illness was a defining aspect of her life, influencing both her personal struggles and creative work. She endured recurring episodes of severe depression, anxiety, and what is now believed to have been bipolar disorder, which began in adolescence following the deaths of her mother and half-sister. These episodes were often triggered by major life events, such as the loss of her father and the stresses of her literary career. While Woolf found solace and expression in writing, her mental health challenges were a constant battle. Despite this, her resilience and ability to channel her struggles into groundbreaking literature remain an enduring testament to her strength.

Woolf’s spiritual perspective was deeply introspective and rooted in a sense of wonder about existence, though she was not traditionally religious. Influenced by her upbringing and intellectual milieu, she rejected organized religion but often explored themes of transcendence, unity, and the sublime in her work. Her writings frequently delve into the interconnectedness of human experience, the fleeting nature of life, and the profound beauty found in everyday moments, reflecting a spiritual sensibility grounded in the contemplation of existence rather than conventional faith.

In 1919, Woolf published her second novel, Night and Day, and in 1922, Jacob’s Room, a groundbreaking work that showcased her innovative narrative techniques. This period also marked her deepening connections within the Bloomsbury Group and her friendships with figures like T.S. Eliot and Lytton Strachey, which enriched her intellectual and creative life.

In 1925, Woolf published Mrs. Dalloway, a novel that explored the inner lives of its characters through stream-of-consciousness techniques. Stream-of-consciousness is a narrative technique that seeks to depict the continuous flow of thoughts, feelings, and sensory impressions within a character’s mind. It often mimics the natural, fragmented, and nonlinear way human thoughts occur, without clear transitions or logical order. This style immerses the reader in the character’s inner experiences, offering a deep and intimate understanding of their psyche. While writers like James Joyce and William Faulkner are also renowned for their use of this style, Carolyn notes that stream of consciousness is not merely a technique but a process of allowing the creative flow to emerge organically, without interference.

In 1927, Woolf’s novel To the Lighthouse was released. This is considered to be one of her masterpieces, blending innovative narrative structure with profound themes of memory and loss. In 1929, she wrote A Room of One’s Own, a seminal feminist essay advocating for women’s independence and creative freedom. In 1931, Woolf published The Waves, an experimental novel that blended poetic prose with the inner monologues of its characters, considered one of her most ambitious works. In 1933, she wrote Flush, a playful biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s dog, showcasing her versatility as a writer.

In 1937, Woolf published The Years, a novel blending family history with social commentary, which became one of her most commercially successful works. In 1938, she released Three Guineas, a feminist polemic critiquing patriarchy and advocating for women’s education and independence. During this time, Woolf faced the growing tensions of World War II, which deeply unsettled her. Her mental health began to deteriorate under the stress of the war and personal pressures, though she remained active in writing and intellectual discussions.

In the final year of her life, Woolf faced a profound decline in her mental health. Despite completing her last novel, Between the Acts, which was published posthumously, she struggled with severe depression and fears that her creative abilities were fading. In 1941, overwhelmed by these feelings, she filled her coat pockets with stones and drowned herself in the River Ouse near her home in Sussex. Woolf’s death, at the age of 59, marked the tragic end of her brilliant and transformative literary career.

Woolf’s legacy lies in her profound influence on modern literature and feminist thought. As a pioneer of modernism, her innovative use of stream-of-consciousness and psychological depth in her novels reshaped narrative techniques and expanded the boundaries of fiction. Her essays remain foundational texts in feminist literature, advocating for women’s creative and intellectual independence. Woolf’s work continues to inspire readers and writers to this day, and she is considered one of the most important literary figures of the 20th century.

Some of the quotes that Virginia Woolf is known for include:

Lock up your libraries if you like; but there is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind.

Books are the mirrors of the soul.

I am rooted, but I flow.

If you do not tell the truth about yourself you cannot tell it about other people.

When you consider things like the stars, our affairs don’t seem to matter very much, do they?

There was a star riding through clouds one night, and I said to the star, ‘Consume me’.

What is the meaning of life? That was a simple question; one that tended to close in on one with years, the great revelation had never come. The great revelation perhaps never did come. Instead, there were little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark.