Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

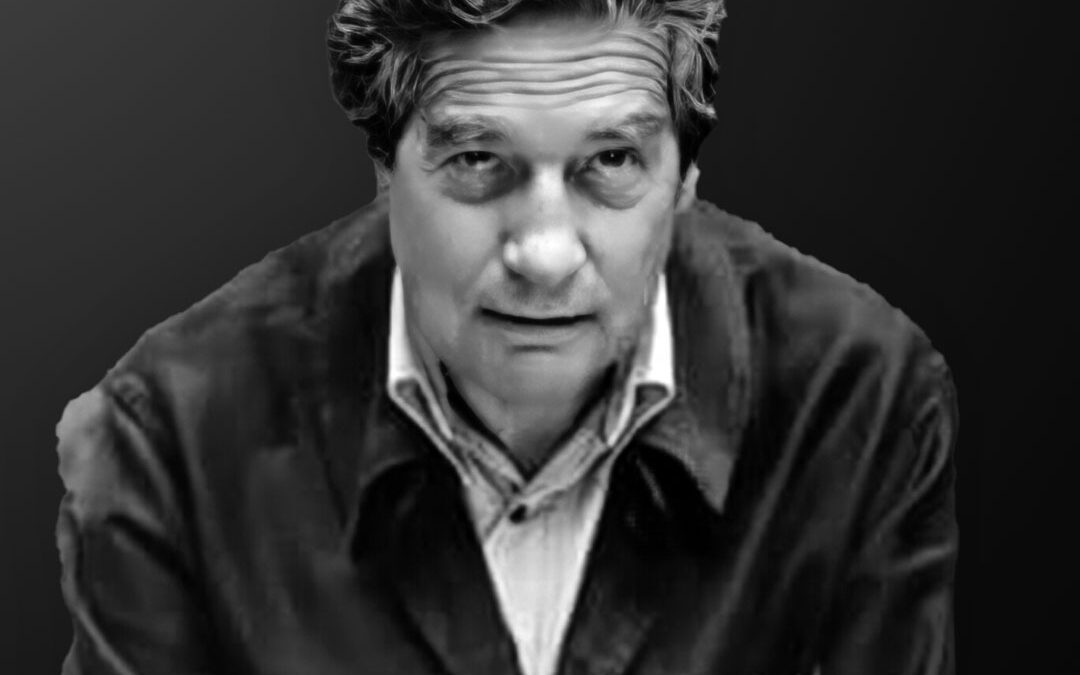

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of cultural anthropologist Carlos Castaneda, who is the author of a dozen popular books, that have sold more than 28 million copies and been published in 17 languages. Castaneda wrote a series of books that describe the supposed training that he received from a wise trickster shaman in Mexico that likely never existed. Despite Castaneda’s accounts probably being fictional, they are still wonderful stories that contain valuable spiritual knowledge, as it seems that the “wise trickster shaman” was Castaneda himself.

Carlos César Salvador Arana was born in Cajamarca, Peru in 1925. Or maybe it was in Sao Paulo, Brazil? Different sources make different claims about his birthplace, and much about his early life remains mysterious because Castaneda offered conflicting autobiographical information. His surname, “Castaneda,” was his mother’s maiden name.

In 1951, Castaneda moved to the U.S., and he became a naturalized citizen in 1957. Castaneda studied anthropology at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he earned his undergraduate and graduate degrees. According to Castaneda’s writings, he met an unusual man in Arizona during the early 1960s named Don Juan Matus, who he described as a Yaqui “sorcerer” from Sonora, Mexico, and was supposedly a powerful shaman who could allegedly manipulate time and space. (The Yaqui are a Native American people that are indigenous to Mexico.)

Castaneda said that he became Don Juan’s apprentice, and in 1965 he returned to LA and began writing about his experiences. In 1968, Castaneda published The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge, a mass market book that also served as his Master’s thesis in the School of Anthropology at UCLA. The book claimed to document the events that took place during Castaneda’s supposed apprenticeship with Don Juan between 1960 and 1965. The book was not only accepted as Castaneda’s master’s thesis at UCLA, but it also became a New York Times bestseller that sold more than 10 million copies.

This bestselling book was followed by two more books about the teachings of Don Juan, which were also written while Castaneda was still an anthropology student at UCLA, and they became equally successful: A Separate Reality and Journey to Ixtlan. Castaneda was awarded a Ph.D. from UCLA based on the work described in these books. However, these accounts of the legendary Yaqui sorcerer are now considered to be fictional by other anthropologists, as there is no evidence that Don Juan Matus ever really existed.

However, the stories were considered factual at the time that they were published, and they even convinced Castaneda’s doctoral committee at the UCLA School of Anthropology to award him with their highest academic honor. Although many critics have questioned the reality of Don Juan, Castaneda always insisted that everything he wrote was true. Despite this controversy over the authenticity, Castaneda’s books became extremely popular due to their engaging storytelling, and their explorations of consciousness, altered states of mind, and spirituality that dovetailed with the zeitgeist of the time.

Around 1972, Castaneda stepped away from the public eye and bought a large multi-dwelling property in Los Angeles, which he shared with some of his students. Two of his students, Taisha Abelar and Florinda Donner-Grau, also wrote books about their experiences with Don Juan’s teachings from a female perspective. Castaneda endorsed both of these books as authentic reports of Don Juan’s teachings: The Sorcerer’s Crossing and Being-in-Dreaming.

Castaneda became a well-known cultural figure during his life, although he rarely appeared in public forums, and he developed a mysterious reputation. Castaneda was the subject of a Time magazine cover article in 1973 that described him as “an enigma wrapped in a mystery wrapped in a tortilla.” In 1974, Castaneda published his fourth book, Tales of Power, which chronicled the supposed end to his apprenticeship with Don Juan, although future books by Castaneda describe further aspects of his supposed training. Castaneda wrote a total of twelve books about the “teachings of Don Juan.”

In the 1990s, Castaneda and his students developed a shamanic system that they called Tensegrity, which is said to be a modernized version of the teachings developed by the Indigenous shamans who lived in Mexico, in times prior to the Spanish conquest. This name for this system was taken from a term coined by the late philosopher Buckminster Fuller to mean “a structural principle based on a system of isolated components under compression inside a network of continuous tension.” In 1995, Castaneda and his students created Cleargreen Incorporated, an organization to promote this shamanic system. Cleargreen continues to teach workshops today.

Castaneda died in 1998 at the age of 72. He died as mysteriously as he had lived. There was no public service; Castaneda was cremated, and the ashes were sent to Mexico. His death was unknown to the outside world until almost two months after he died when an obituary appeared in The Los Angeles Times.

Some of the quotes that Carlos Castaneda is known for include:

You have everything needed for the extravagant journey that is your life.

The trick is in what one emphasizes. We either make ourselves miserable, or we make ourselves happy. The amount of work is the same.

The basic difference between an ordinary man and a warrior is that a warrior takes everything as a challenge, while an ordinary man takes everything as a blessing or a curse.

The aim is to balance the terror of being alive with the wonder of being alive.

Forget the self and you will fear nothing, in whatever level or awareness you find yourself to be.

All paths are the same: they lead nowhere. … Does this path have a heart? If it does, the path is good; if it doesn’t, it is of no use. Both paths lead nowhere; but one has a heart, the other doesn’t. One makes for a joyful journey; as long as you follow it, you are one with it. The other will make you curse your life. One makes you strong; the other weakens you.

Life in itself is sufficient, self-explanatory and complete.

Seek and see all the marvels around you. You will get tired of looking at yourself alone, and that fatigue will make you deaf and blind to everything else.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of the late neuroscientist and pharmacologist Candace Pert, who conducted groundbreaking research that changed the way scientists view the relationship between mind and body, and was a major proponent of alternative medicine. Pert discovered the opiate receptor— the cellular binding site for endorphins in the brain— and she paved the way for the field of mind-body medicine.

Candace Beebe Pert was born in 1946 in New York City. Her father was a commercial artist and her mother worked in the courts as a clerk typist. Although Pert was initially interested in studying psychology, she studied biology in college and sought a more solid scientific basis for understanding human behavior. Pert completed her undergraduate studies in biology cum laude in 1970 at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania.

In 1972, while still a graduate student in her mid-twenties at Johns Hopkins University, Pert discovered the opiate receptor, the molecular-docking site where drugs like opium and morphine bind to nerve cells in the human brain. This breakthrough finding led to the discovery of endorphins— natural, painkilling opiate-like chemicals in the brain, which Pert refers to as “the underlying mechanism for bliss and bonding.”

These findings dramatically increased our understanding of how drugs interact with the nervous system, and how the body and brain communicate with each other. Pert went on to discover numerous receptor sites for other drugs and naturally occurring substances in the brain, and she helped map the chemical communication system that operates between the brain and the immune system. This paved the way for an understanding of mind-body medicine and the biochemical basis for emotions.

In 1974, Pert received her Ph.D. in pharmacology, with distinction, from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, where she worked in the laboratory of Solomon Snyder. From 1975 to 1987, Pert conducted research at the National Institute of Mental Health, where she served as Chief of the Section on Brain Biochemistry in the Clinical Neuroscience Branch. In 1987, Pert founded a private biotech laboratory that she directed for a few years, and then conducted AIDS research in the Department of Physiology and Biophysics at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington D.C.

Pert spent over forty years trying to decode the biochemical language of what she refers to as the body’s “information molecules”— such as peptides and other ligands— which regulate the biochemical aspects of human physiology. Her interdisciplinary model of the “body-mind” explains how these chemicals distribute information simultaneously to every cell in the body. This understanding has unlocked the secret of how our emotions can literally create or destroy our health.

Many people believe that Pert should have won the Nobel Prize for her discovery of the opiate receptor— which is considered one of the most important discoveries in the history of neuroscience— but that internal politics interfered with her being properly recognized for her work. In this regard, it is important to note that Pert discovered the opiate receptor only after her supervisor had specifically ordered her to stop looking for it, concluding that it was a fruitless search, and Pert had to continue her research in secret.

Pert’s supervisor, Solomon Snyder, was later awarded the Lasker Award (an award for outstanding medical research) for its discovery without her. Such omissions are common in the world of science; contributions by graduate students in a research lab are rarely acknowledged beyond listing them as the primary author on the published article. However, Pert did something unusual: she protested, sending a letter to the head of the foundation that awards the prize, saying she had “played a key role in initiating the research and following it up” and was “angry and upset to be excluded.” Her letter caused significant discussion in the field, and many saw her exclusion as a typical example of the barriers women face in science careers.

In 1997, Pert’s book, Molecules of Emotion: Why You Feel the Way You Feel, was published. It recounts the story of her revolutionary discovery, the development of her research, and the evolution of her philosophy, as well as the storm of controversy that formed around her work. It reads like a spellbinding action-adventure story and offers a personal and insightful reinterpretation of neuroscience and mind-body medicine.

In 2001, Pert was featured in Washingtonian magazine as one of Washington’s fifty “Best and Brightest” individuals, and she was featured in Bill Moyers’s highly acclaimed PBS television series Healing and the Mind, as well as in the companion book that went with the series. Pert created the audio series Your Body Is Your Subconscious Mind, and also a psychoactive CD to enhance healing and personal transformation called To Feel Go(o)d.

Pert lectured extensively about the implications of her research for mind-body medicine, and her work helped to heal the pathological divisions in Western culture between mind and body, science and spirituality. “Finally, here is a Western scientist who has done the work to explain the unity of matter and spirit, body and soul!” wrote physician Deepak Chopra in the introduction to her book.

Pert’s research interests have ranged from decoding “information molecules” to trying to find cures for cancer and AIDS. She held a number of patents for modified peptides in the treatment of psoriasis, Alzheimer’s disease, chronic fatigue syndrome, stroke, and head trauma. One of these, peptide T, was found to be helpful for the treatment of AIDS. Pert has published more than 250 scientific papers on peptides and their receptors, and the role of these neuropeptides in the immune system. Some of Dr. Pert’s papers are among the most cited scientific papers in human history.

Pert died in 2013 at the age of 67. She is remembered for the important role that she played in how Mind-Body medicine became recognized as an area of legitimate scientific research. According to Pert’s website, her fans refer to her as The Mother of Psychoneuroimmunology and The Goddess of Neuroscience. A book about Pert’s life by Pamela Ryckman was recently published, Candace Pert: Genuis, Greed, and Madness in the World of Science.

I interviewed Candace Pert in 2004 for my book Conversations on the Edge of the Apocalypse. Candace generates a lot of warmth and positive energy. She gets excited and enthusiastic about her ideas, and she laughs a lot. My impression of Candace was that she was like an octopus, capable of doing innumerable tasks at once. Here are some excerpts from our conversation:

David: John Lilly was a big fan of your work. That’s how I first found out about you actually. He used to talk about you a lot.

Candace: I have pictures of him and me. He came to the National Cathedral. He was wonderful. God, that’s such a shame when people have to die. I’ve had people close to me die, and sometimes I think there are some amazing communications and synchronicities, where you think that they are trying to communicate, or some aspect of what has survived is coming back. There are some amazing stories, with things like doors slamming. I’ve had a few things happen at funerals. I’ve been through quite a few funerals in the last few years, and have seen things like leaves swirling at critical moments in the burial ceremony. There’s stuff that seems kind of amazing.

David: What is your concept of God, and do you see any teleology in evolution?

Candace: We don’t have to say that evolution is guided by intelligence, but it’s very clear to me that the process itself— stars cooling, entropy, evolution— is always leading toward more and more complexity and more and more perfection. So, the actual physical laws of the universe are God. You don’t have to invoke anything beyond that. I mean, God is not incompatible with the laws of science. God is a manifestation of that. There’s no incompatibility. We’re not talking about The Bible; we’re talking about the true laws of science. So, I guess that’s why I’m so into truth-seeking because truth-seeking is God-seeking at the same time.

David: What do you think happens to consciousness after death?

Candace: That’s a great question. Years ago, I had to answer that question to get a big honorarium, so I participated, and what I said then is still relevant. It’s this idea that information is never destroyed. More and more information is constantly being created, and it’s not lost, and energy and matter are interconvertible. So somehow there must be some survival because one human being represents a huge amount of information. So, I can imagine that there is survival, but I’m not sure exactly what form that it takes. I think Buddhist practice is interesting. There’s this whole idea that you’re actually preparing yourself for death, and if you do it just right you can make the transition better.

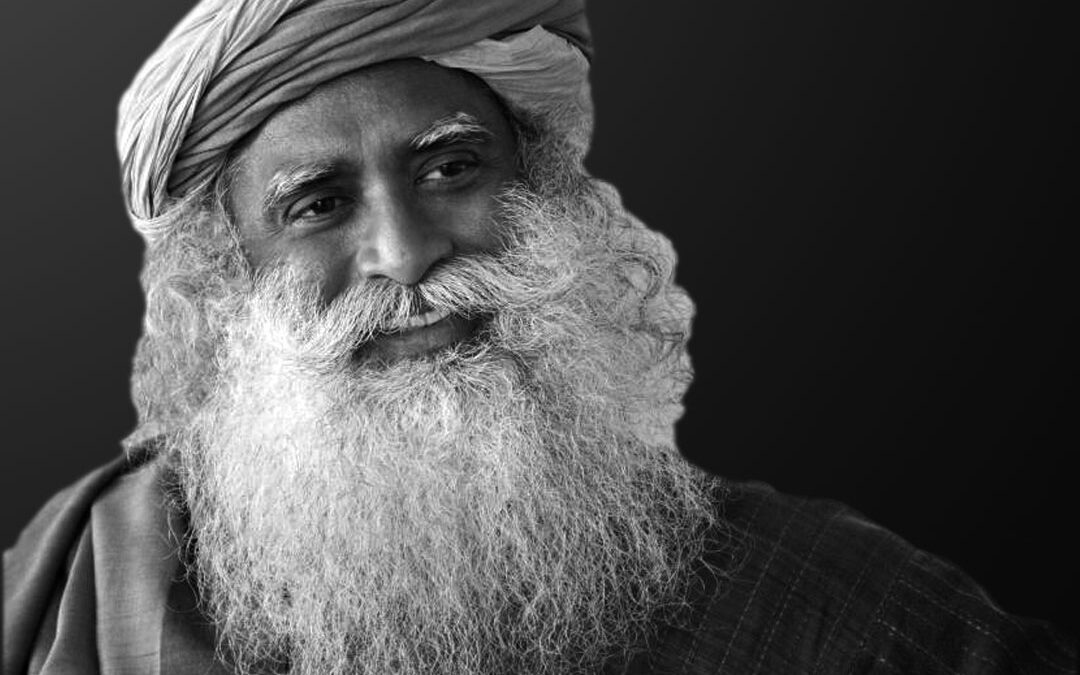

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of Yogi, spiritual teacher, and environmentalist Sadhguru, who is the founder of the Isha Foundation in India. He is the author of several bestselling books and is the recipient of numerous awards for his valuable ecological work. Sadhguru Jagadish Vasudev was born in 1957 in Karnataka, India. His father was an ophthalmologist and his mother was a homemaker. He was the youngest of five children.

After Vasudev completed his formal education, he enrolled at the University of Mysore in India, where he performed well studying English literature. After graduating from school, Vasudev built a poultry farm in Mysore. The farm became a successful business, and it required minimal attention throughout the day, so Vasudev was able to pursue other interests during his time off, such as writing poetry.

In 1982, at the age of 25, Vasudev had a spiritual experience that changed his life. He drove up a hill in Mysore and sat out on a rock. As he was sitting there, Vasudev had a boundary-dissolving mystical experience that he described like this, “All my life I had thought, this is me…But now the air I was breathing, the rock on which I was sitting, the atmosphere around me— everything had become me.”

After having a similar spiritual experience around six days later, Vasudev shut down his poultry business and he began to travel around India on his motorcycle, seeking insight into his spiritual experience. Vasudev developed a love for riding motorcycles. One of his favorite places to ride was the Chamundi Hills in Mysore, although he sometimes drove as far as Nepal. In 1983, after about a year of meditation and travel, Vasudev felt inspired to teach yoga in Mysore, to share his transformative, inner experience with others.

Vasudev took the name “Sadhguru,” which means “uneducated guru.” A guru is a “dispeller of darkness,” or a teacher, and Sadhguru means a teacher who does not come from a lineage of gurus. In other words, he’s a self-taught guru. In 1992, Vasudev established the Isha Foundation, a nonprofit, spiritual organization and yoga center in Coimbatore, India. The foundation offers a system of yoga that combines postural yoga with chanting, breathing, and meditation. They also have initiatives to improve the quality of education in rural India, and the organization is supported by over nine million volunteers in more than 300 centers worldwide.

Through the Isha Foundation, Sadhguru has launched several ecologically oriented projects and campaigns focused on environmental conservation and protection. In 2017, Sadhguru launched Rally for Rivers, a campaign intended to build widespread support for river revitalization efforts across India, and in 2019, he launched the Cauvery Calling campaign, which focused on planting trees along the Cauvery River, to replenish depleted water levels.

In 2017, Sadhguru received the Padma Vibhushan, India’s second-highest civilian award, for his “contributions to spirituality and humanitarian services,” and in 2018 the president of India awarded him the Rashtriya khel Protsahan Puraskar, an honor for organizing India’s largest rural sports festival. In 2022, Sadhguru completed a 100-day motorcycle journey from London to India, to bring attention to his Journey to Save Soil campaign, which focuses on raising awareness about soil degradation issues and the benefits of using organic matter in farming.

According to India Today, in 2019 Sadhguru was one of the fifty “most powerful” people in India. He ranked number 40, and he was included because his Rally for Rivers campaign was the largest ecological movement ever, with support from over 162 million people. Sadhguru has appeared on many popular talk shows talking about his ecological campaigns, including the Joe Rogan podcast and The Daily Show.

Sadhguru is actively involved in an assortment of diverse and creative fields, such as architecture and visual design. He is the designer of several unique buildings and consecrated spaces at the Isha Yoga Center. Sadhguru also writes poetry and paints, and some of his artwork can be found on display at the Isha Foundation.

Sadhguru has authored over thirty books, including the New York Times bestsellers Inner Engineering: A Yogi’s Guide to Joy and Karma: A Yogi’s Guide to Crafting Your Destiny. His book Eternal Echoes is a collection of his poetry from 1994 to 2021.

Some of the quotes that Sadhguru is known for include:

Every moment there are a million miracles happening around you: a flower blossoming, a bird tweeting, a bee humming, a raindrop falling, a snowflake wafting along the clear evening air. There is magic everywhere. If you learn how to live it, life is nothing short of a daily miracle.

Whether you are a man, woman, animal, or an ant – the Source of Life is Within You.

A human is not a being; he is a becoming. He is an ongoing process – a possibility. For this possibility to be made use of, there is a whole system of understanding the mechanics of how this life functions and what we can do with it, which we refer to as yoga.

Mind is not in any one place. Every cell in this body has its own intelligence. The brain is sitting in your head, but mind is all over the place.

You may not be able to shape every situation in your life, but you certainly have the potential to determine how you experience every moment of your life.

This is the power of Inner Engineering.

In yogic culture, Growth means Dissolution. You dissolve your limited persona to become as vast as the Universe. When you are nothing, in some way, you are everything.

What happened yesterday, you cannot change. What is happening today, you can only experience. What is tomorrow, you have to Create.

The sign of intelligence is that you are constantly wondering. Idiots are always dead sure about every damn thing they are doing in their life.

The most beautiful moments in life are moments when you are expressing your joy, not when you are seeking it.

If you resist change, you resist life.

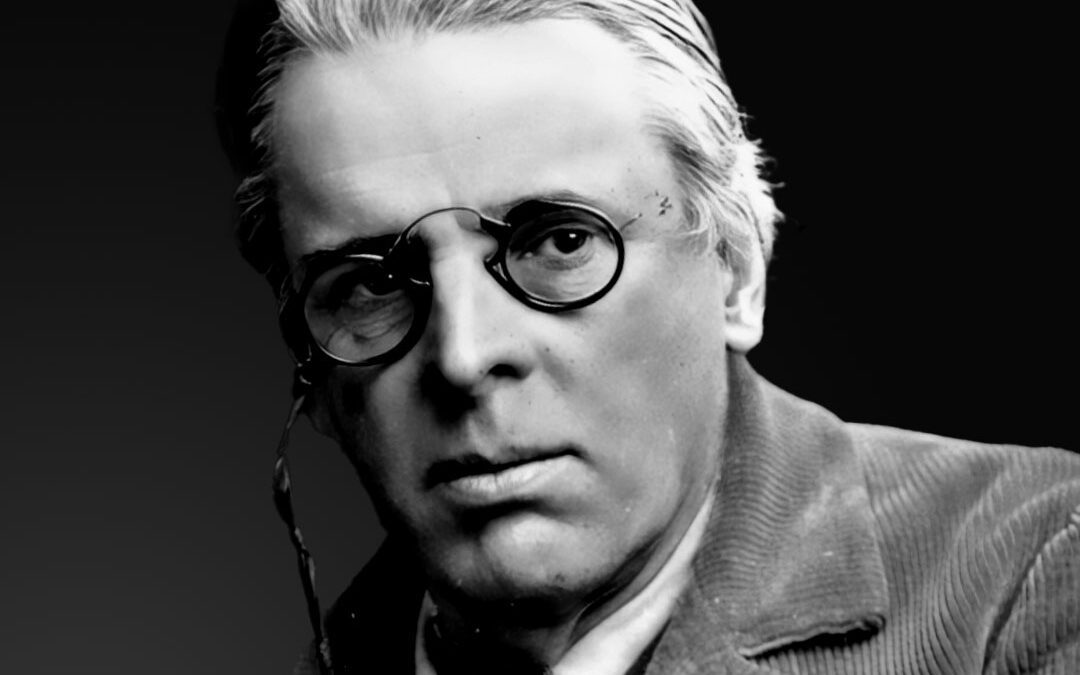

Carolyn and I have admired the work of Irish poet and playwright William Butler Yeats, who won the 1923 Nobel Prize in Literature, and whose work was inspired by his mystical experiences. Yeats was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival, a movement that renewed interest in aspects of Celtic cultures, and he co-founded the Abbey Theatre in Dublin.

William Butler Yeats was born in Sandymount, Ireland in 1865. Yeats’ mother came from a wealthy merchant background, and his family was unusually creative. Jervis Yeats, William’s great-great-grandfather, was a well-known painter, and his father, brother, and sisters, were all painters or artists. In 1867, the family moved to London to aid their father in his career as a portrait painter.

Yeats received his initial education at home, where his mother entertained him with Irish folktales. He read poetry from an early age and was fascinated by Irish legends. In 1877, Yeats entered the Godolphin School in West London, where he studied for four years. Yeats had difficulty with language because he was tone-deaf. He was also a poor speller due to dyslexia, and so was “only fair” in his academic performance.

That same year Yeats began writing his first poetry when he was seventeen. He was influenced by the work of Percy Bysshe Shelley and William Blake, and he wrote early poems about love, magicians, monks, and a woman accused of paganism.

In 1880, Yeats’ family returned to Dublin for financial reasons. Yeats resumed his education at Dublin’s Erasmus Smith High School. His father’s studio was nearby, and Yeats spent a great deal of time there, where he met many of the city’s artists and writers. In 1885, the Dublin University Review published Yeats’ first poems, as well as an essay entitled The Poetry of Sir Samuel Ferguson. Between 1884 and 1886, Yeats attended the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin.

In 1889, Yeats’ first volume of verse, The Wanderings of Oisin and Other Poems, was published. It is slow-paced lyrical poetry that tells the story of a mythical hero who embarks on a journey to the Land of Youth, and is notable for its use of vivid imagery, mythological references, and a sense of nostalgia for Ireland’s past.

Yeats had mystical experiences throughout his life, and he describes having had visionary encounters with spirits or supernatural beings since childhood. Yeats said that he had visions of a figure that appeared to be a spiritual guide and that this figure communicated with him, and provided him with insights and wisdom about life and art. Yeats was deeply interested in mysticism, the occult, and the esoteric, and these interests were reflected in his poetry and writings. For example, in the following excerpt from his poem Vacillation, Yeats describes how he felt during a mystical experience:

“While on the shop and street I gazed,

My body for a moment blazed,

And twenty minutes, more or less,

It seemed, so great my happiness,

That I was blessed and could bless.”

In 1890, Yeats joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a secret society in Great Britain devoted to the study and practice of ritual magic, the occult, metaphysics, and spiritual development, and his interest in mysticism was further informed by Hinduism, astrology, spiritualism, and theosophical beliefs. Yeats also believed in fairies, that they are real, living creatures.

The late 19th Century saw a literary movement called The Irish Literary Revival, which was a flowering of Irish creative talent in poetry, music, art, and literature. There were two main hubs, London and Dublin, and Yeats was considered a major figure in this movement. In 1888, he published Fairy and Folk Tales of Irish Peasantry, and in 1893, he published The Celtic Twilight, a collection of folklore and reminiscences from Ireland that were important to this moment.

Yeats also wrote plays. In 1903 he published On Baile’s Strand, about the Irish mythological hero Cuchulain, which was first performed at the grand opening of the Abbey Theatre in Dublin in 1904. The Abbey Theatre — which is one of Ireland’s leading cultural institutions — was co-founded in 1899 by Yeats, along with Lady Gregory and Edward Martyn. The Abbey Theatre was the first state-subsidized theatre in the English-speaking world, and the performances there played to a mainly working-class audience, rather than the usual middle-class Dublin theatergoers. Some of Yeats’ other plays included Dierdre and The King of the Great Clock Tower. In 1917, Yeats married Georgia Hyde-Less, who was 25 years younger, and they went on to have two children together. During their marriage, the couple experimented with various techniques for spirit contact, and communication with spirits, who they referred to as their “instructors.”

Yeats was politically motivated, and he was a part of the Irish Nationalist Movement that asserted that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. In 1922, Yeats was appointed Senator for the Irish Free State, and he served two terms, until 1928. His time as a senator allowed him to contribute to the cultural and political landscape of Ireland in different ways.

In 1923, Yeats was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for “his always inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation,” beating out Nietzsche’s sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche.

In 1925, Yeats published a book-length study of various philosophical, astrological, and poetic topics titled A Vision, which he wrote while experimenting with “automatic writing” with his wife, and serves as a “meditation on the relationships between imagination, history, and the occult.” This work was substantially revised by Yeats in 1937.

In 1934, Yeats received a controversial Steinach operation (a half of a vasectomy) which supposedly “rejuvenated” him for the last five years of his life. Yeats was reported to find “new vigor, evident from both his poetry and his intimate relations with younger women,” which he described as a “second puberty.”

Yeats died in 1939 in Menton, France at the age of 73. During his lifetime, Yeats published more than 100 works of poetry, drama, and prose, and was a towering figure in the world of English literature. In 1989, sculptor Rowan Gillespie created an eight-foot statue of Yeats, that now stands in front of the Ulster Bank Building on Stephen Street in Sligo, Ireland.

Some of the quotes that William Butler Yeats is known for include:

There are no strangers here; only friends you haven’t yet met.

Do not wait to strike till the iron is hot; but make it hot by striking.

Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire.

Come Fairies, take me out of this dull world, for I would ride with you upon the wind and dance upon the mountains like a flame!

Happiness is neither virtue nor pleasure, nor this thing nor that, but simply growth. We are happy when we are growing.

Think like a wise man but communicate in the language of the people.

How can we know the dancer from the dance?

What can be explained is not poetry.

If suffering brings wisdom, I would wish to be less wise.

Life is a long preparation for something that never happens.

The innocent and the beautiful have no enemy but time.

How far away the stars seem, and how far is our first kiss, and ah, how old my heart.

Take, if you must, this little bag of dreams, Unloose the cord, and they will wrap you round.

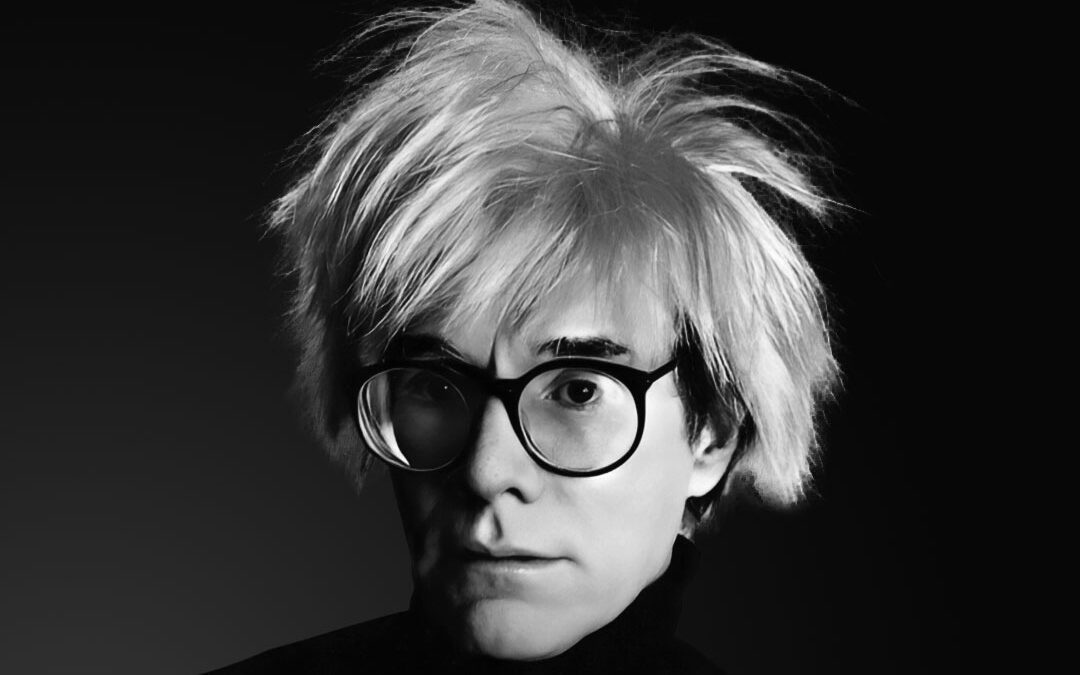

Carolyn and I have admired the work of visual artists, film directors, and leading figures in the Pop Art movement Andy Warhol. His work explores the relationship between artistic expression, advertising, and celebrity culture, in a variety of media, including painting, silk-screening, photography, film, and sculpture. Warhol’s work embraces and celebrates the banality of American culture, and he is well known for his witty and insightful quotes.

Andrew (Andy) Warhola Jr. was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1928. He was the fourth child in a working-class family, whose parents were emigrants from a geographical region that is now located in Slovakia. Warhol’s father worked in a coal mine and died in a car accident when Andy was thirteen.

In 1936, when Warhol was eight years old, he became infected with a nervous system affliction that caused involuntary movements in his extremities, and he was confined to bed for over two months. Warhol described this period as being an important developmental stage in his life, which was largely spent listening to the radio and collecting pictures of movie stars around his bed.

In 1945, Warhol graduated from Schenley High School in Pittsburgh, and he won a Scholastic Art and Writing Award. Warhol enrolled at Carnegie Mellon University, where he studied commercial art. In 1947 and 1948 Warhol’s illustrations appeared on the cover and interior of his student magazine. In 1949, Warhol earned his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in pictorial design, and his first commissions were to draw shoes for Glamour magazine.

In 1950, Warhol moved to New York City, where he began a career in magazine illustration and advertising, and his first job in the city was designing shoes for a shoe manufacturer. While working in the shoe industry, Warhol developed a “blotted line” printing technique, which involved applying ink to paper and then blotting the ink while still wet. His use of tracing paper and ink allowed him to repeat— and to create endless variations— of a basic image; a process that became important in his later work.

In 1952, Warhol had his first solo show, of his whimsical ink drawings of shoe advertisements, at the Hugo Gallery in New York (although that show was not very well received). In 1956, some of his work was included in a group exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in NYC. Warhol began creating art by tracing projected photographs, subtly alerting the image, such as his 1956 image of a Young Man Smoking a Cigarette.

It was around this time, in the late 1950s, that Warhol was hired by RCA Records to design record album covers and promotional materials. In 1962, Warhol learned silk screen printmaking techniques, and he began to participate in the Pop Art movement. Pop Art was a British and American art movement that emerged in the mid to late 1950s, and is based on imagery from modern popular culture and the mass media. Pop Art was largely viewed as a critical or ironic comment on traditional fine art values, and often used imagery that had been commonly used in advertising or comic books.

In 1962, Warhol was featured in an article in Time magazine with his painting Big Campbell’s Soup Can with Can Opener (Vegetable), which became his most sustained motif— the Campbell’s soup can. The painting was exhibited at the Wadsworth Museum in Connecticut that year, and a year later Warhol made his West Coast debut with his Campbell’s Soup Cans exhibition at Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. That same year, Warhol also had exhibits at the Stable Gallery and the Museum of Modern Art in NYC, including a silkscreened painting series of iconic American images and objects, such as Marilyn Monroe portraits, Coca Cola bottles, and $100 bills.

In 1963, Warhol rented an old firehouse on East 47th Street in NYC that became his art studio and would turn into a legendary location called The Factory, where Warhol’s workers made silkscreens and lithographs under his direction. The Factory became famous for its exclusive parties in the 1960s, and was a hip hangout for artists, musicians, and celebrities, such as Allen Ginsberg, Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, and the Velvet Underground. Warhol created a Pop Art empire, and at exhibits he sold autographed soup cans and “sculptures” of boxes with commercial logos on them.

In 1968, there was an assassination attempt on Warhol by a radical feminist writer named Valerie Solanas, who shot Warhol at The Factory, but only minor injuries were sustained. Solanas was subsequently arrested and diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia.

In 1969, Warhol co-founded Interview magazine with a British journalist. The magazine features in-depth, usually unedited interviews with celebrities, artists, musicians, and creative thinkers. It is still in print today.

In 1971, Warhol had a retrospective exhibition of his work at the Whitney Museum of American Art in NYC. In 1975, he published his book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, which is a loosely formed autobiography. Although criticized as being merely a “business artist,” some critics have come to view Warhol’s superficiality and commerciality as “the most brilliant mirror of our times,” contending that “Warhol had captured something irresistible about the zeitgeist of American culture.”

Warhol also directed or produced hundreds of experimental films, and dozens of full-length movies—silent and sound, short and long, scripted and improvised— fifty of which have been preserved by the Museum of Modern Art. The styles range from minimalist avant-garde to more commercial productions. The Andy Warhol Film Project seeks to preserve Warhol’s nearly 650 films.

Warhol once said, “I’d like to be a machine, wouldn’t you?” In 1981, he got his wish when he worked on a project that was to create a traveling stage show— called A No Man Show— with a life-sized animatronic robot in the image of Warhol. The Andy Warhol Robot would then be able to read Warhol’s diaries as a theatrical production. This project was left unfinished when Warhol died, and over $400,000 was spent to create a Warhol robot, which is now in the hands of a private collector.

Warhol died in 1987 in New York City. After he died, Warhol’s body was brought back to Pittsburgh, where an open-coffin wake was held. The solid bronze casket had gold-plated rails and white upholstery. Warhol was dressed in a black cashmere suit, a paisley tie, a platinum wig, and sunglasses. He was laid out holding a small prayer book and a red rose, and the coffin was covered with white roses and asparagus ferns.

Warhol is remembered as one of the founding fathers of the Pop Art movement, and for challenging the very definition of art. Warhol’s artistic risks, and his lifelong experimentation with different subjects and media, made him a pioneer in almost all forms of visual art.

Some of the quotes that Andy Warhol is known for include:

Don’t pay any attention to what they write about you. Just measure it in inches.

If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.

In the future, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes.

Art is already advertising. Mona Lisa could have been used to support a brand of chocolate, Coca-Cola, or anything else.

Being born is like being kidnapped. And then sold into slavery.

I am a deeply superficial person.

We seek to last more than we try to live.

When you work with people who misunderstand you, instead of getting transmissions, you get transmutations, and that’s much more interesting in the long run.

Carolyn and I have admired the work of Welsh poet, playwright, opera librettist, and biographer Peter Thabit Jones, who is the author of sixteen books, has won numerous awards for his poetry, and is regarded as an expert on the life of Dylan Thomas.

Peter Thabit Jones was born in Swansea, Wales in 1951. He was raised near Kilvey Hill, by his grandmother. His only memories of his grandfather are of him being “seriously unwell” in a bed in their parlor. Thabit Jones said that his grandfather’s nearness to death at a young age made him “really focus on life.”

Thabit Jones describes his earliest memory as being of the landscape that he could see from his home. As a toddler, he recalls looking out through the open kitchen door of his grandmother’s home and seeing Kilvey Hill, which he has described as a “huge, hulking shape” that dominated the area. As a child, Thabit Jones explored “every corner” of Kilvey Hill and the terrain of Eastside Swansea, and it was here that he developed his “pantheistic belief… that we are connected to nature.”

Thabit Jones describes Kilvey Hill as “the touchstone to that reality that, down the years, changed into memories: my first bonfire night, first gang of boys, first camping experience, first love.” In 1999 Thabit Jones published a book of poems inspired by his time there, called the The Ballad of Kilvey Hill, and in 2007 his poem Kilvey Hill was incorporated in a stained glass window, created by Welsh artist Catrin Jones, in the Saint Thomas Community School in Eastside Swansea.

As Thabit Jones grew older, he explored the busy docks nearby, the beach, and the seaside town of Swansea. He was “curious about the reality of things” and “the depth of experience.” Thabit Jones began reading the work of well-known poets, such as Wordsworth, Tennyson, R.S. Thomas, Dylan Thomas, and Ted Hughes. Reading the work of these monumental poets helped Thabit Jones to realize that he was “not alone in wanting, almost needing, to see ‘shootes of everlastingness’ beyond the curtain of reality.”

It was in 1975 that Thabit Jones began to find his own voice as a poet. Thabit Jones describes the turning point in his life as occurring after the death of his second son, Mathew, when he experienced deep personal grief.

In 1993, Thabit Jones began tutoring English literature and creative writing at Swansea University, which he continued doing until 2015.

In 1997, Thabit Jones began corresponding with New York poet, critic, and Professor Vince Clemente, who helped to inspire him, and they began sharing poems in progress. That same year, Thabit Jones visited New York University, as well as other schools and organizations in New York and New Jersey, where he gave poetry readings. In 2001, Clemente, via correspondence, introduced Thabit Jones to American publisher and poet Stanley H. Barkan, who has been a great supporter of Thabit Jones and his writings and is also Carolyn’s publisher.

In 2005, Thabit Jones founded the international poetry magazine The Seventh Quarry, which he edits to this day. In 2006, The Seventh Quarry was awarded the second best Small Press Magazine Award by Purple Patch U.K. Awards.

Thabit Jones is a recognized expert on the life of Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, who I wrote a profile about a number of months ago. In 2008, Thabit Jones embarked on a six-week Dylan Thomas Tribute Tour of America— from New York to California— with Aeronwy Thomas, daughter of Dylan Thomas. The tour was organized by Clemente and Barkan, who they shared as a publisher. It was on this trip— where they visited a number of cities across the country, lecturing, answering questions, and reading prose and poetry by Dylan Thomas— that Thabit Jones first met Carolyn, and their adventure is recounted in Thabit Jones’ commemorative book America, Aeronwy, and Me.

At the end of their tour, Thabit Jones and Thomas were commissioned by the Welsh Assembly Government in New York to write the book Dylan Thomas: Walking Tour of Greenwich Village. Their book serves as a self-guided tour of ten places in Greenwich Village, New York, associated with Dylan Thomas, and it contains a foreword by Hannah Ellis, the granddaughter of Dylan Thomas. Thabit Jones’ guided journey is also available as a smartphone app and as an escorted tour through New York Fun Tours.

In 2017, Thabit Jones published a book of his play The Fire in the Wood, which is about the life of Edmund Kara, the celebrated Big Sur sculptor that I wrote a profile about a number of months ago. That year it was performed at the Actors Studio of Newburyport in Massachusetts, and in 2018 it was performed at the Carl Cherry Center for the Arts in Carmel, California.

Thabit Jones has taught numerous writing workshops throughout Europe, does poetry readings around the world, and his poetry has been published in many magazines, literary journals, and newspapers, such as the U.K. Poetry Review, the Salzburg Poet’s Voice, and the New England Review. He is the author of sixteen books, including The Lizard Catchers, Garden of Clouds, Under the Raging Moon, A Cancer Notebook, and Poems from a Cabin in Big Sur.

Thabit Jones’ poetry has been translated into over twenty-two languages, and he is the recipient of numerous awards, including First Prize in the International Festival of Peace Poetry in 2007, the Eric Gregory Award for Poetry, The Society of Authors Award, The Royal Literary Fund Award, and the Homer European Medal for Poetry and Art.

For a number of years, Thabit Jones has spent his summers as writer-in-residence at the cabin by Carolyn’s home in Big Sur, and he is the author of The Fathomless Tides of the Heart, which is an inspiring and enthralling biography of Carolyn that was just published this year.

In an interview with Peter Thabit Jones conducted in 2009 by Kathleen O’Brien Blair, he shares some of his thoughts on how he writes his poetry, and humanity’s relationship with nature. Here are some excerpts from their conversation:

Kathleen: What is it about the little things and passing vignettes of life that catch your attention?

Peter: I think the little things are all revelations of the big things, thus when observing something like a frog or a lizard one is observing an aspect of creation, a thing that is so vital and part of the larger pattern that none of us really understand. Edward Thomas said, ‘I cannot bite the day to the core’. In each poem I write I try to get closer to the core of what is reality for me, be it the little things or the big things such as grief and loss.

Kathleen: When you write, do you write a poem and then pare it down to its bones, or do the bones come first?

Peter: For me the bones come first, a word, a phrase, a line, or a rhythm, usually initiated by an observation, an image, or a thought. Then once I have the tail of a poem I start thinking of its body. Nowadays, within a few lines, I know if it will be formal or informal. If it is formal, all my energies go into shaping it into its particular mold, a sestina, or whatever. If it is informal, I apply the same dedication. Eventually after many drafts, a poem often then needs cutting back because of too many words, lines, or ideas. R.S. indicated that the poem in the mind is never the one on the page, and there is so much truth in that comment. The actual writing of a poem for me is the best thing about being a poet: publication, if possible, is the cherry on the cake.

Kathleen: Wildness and nature always seems to overcome our best efforts to cage, encrust, or otherwise tame it. Why do you think so many people, and the modern world as a whole, think they can best it? What is it about people, do you think, that they just have to keep trying at that?

Peter: Well, man has to dominate, not just nature but each other. Man strives to be godlike and getting nature/wildness under his thumb maybe confirms that side of his ego. Maybe there is an element of envy too, the freedom of an eagle in the sky, the sheer force of a river, the dignity of a mountain. Modern man has also lost his respectful relationship with nature. Pre-literate people understood and appreciated the preciousness of the world they inhabited, that they were mere brief visitors to the Earth, protectors of it for the generations to come.