Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of English musician, composer, and producer Cosmo Sheldrake, whose improvisational work blends music from various instruments with audio samples from natural environments. His multilayered, multi-instrumentalist compositions have received much notoriety. Cosmo is also the youngest son of British biologist Rupert Sheldrake and voice instructor Jill Purce, and the brother of mycologist Merlin Sheldrake, who I wrote previous profiles about.

Cosmo Sheldrake was born in 1989 in London, England. With a father and brother who are visionary scientists, and a mother who is a sound healer, Cosmo grew up in an extremely creative environment, where art, science, and spirituality were an integral part of his home life.

Cosmo started making music at a young age. He learned to play the piano at the age of four, and at the age of seven, Cosmo made the transition from classical music to blues. By his mid-teens, he was recording and producing his music. Cosmo said that the piano was “an unwieldy instrument” and you “can’t cart it around,” so instead, he taught himself several other instruments, which play a role in his music today.

Cosmo studied anthropology at the University of Sussex, although he said that it was the scope and diversity of music that was exciting for him. He stopped taking formal music lessons as a teenager and instead followed his own set of interests. In 2014, Cosmo began releasing music, when his debut single, The Moss was released. The song received good reviews, and that year, The London Telegraph described him as a “musical visionary.”

In 2017, Cosmo’s debut album, The Much Much How How and I was released. It was written under the influence of a diverse group of musicians— ranging from The Beatles and The Kinks to Moondog and Stravinsky— and was shaped by his study of anthropology, his longstanding interest in ethnomusicology, and a trip to Mardi Gras in New Orleans.

Some of Cosmo’s other albums include Ear to Ear, and Let the World. His multilayered, whimsical, and imaginative music uses sound samples from different objects and animals from around the world. Although he sometimes performs his music alone, with a keyboard and a laptop, Cosmo now plays about 30 instruments, including jazz and classical piano, banjo, double bass, drums, didgeridoo, penny whistle, and sousaphone. He uses a digital loop station to make creative adjustments to his voice, and he is capable of Mongolian throat singing and Tibetan chanting. Cosmos’s music is really fun and upbeat, positive, feel-good sound therapy that always makes me happy when I listen to it.

Cosmo has provided music for film and theater, including the score for a series of Samuel Beckett plays at the Young Vic Theater in London. Sheldrake performs solo, and sometimes with several bands, including Johnny Flynn & the Sussex Wit and the Gentle Mystics. In 2019, his song Come Along was featured in an advertisement for Apple’s iPhone, and subsequently, this song charted at number 39 on the U.S. Digital Songs chart.

A reviewer in The Guardian describes Cosmo’s music as having “a whimsical kind of intelligence… and [his songs] talk about everything from the way moss grows on the north side of trees to what it’s like to be a fly— and the melodies… exude waggish mischief.”

Cosmo is also passionate about fermentation. He and his brother Merlin built a small fermentation lab, where they make various ciders, and have recently started producing their own uniquely fermented hot sauce under the label Sheldrake & Sheldrake.

I first met Cosmo when he was six years old, while I was staying at his home in London when working with his father on the book Dogs That Know When Their Owners are Coming Home, for which I did California-based research. Cosmo’s playful creativity was evident even then when I first spent time with him as a child.

Here is an excerpt from an interview with Cosmo Sheldrake by Richard Ainslie:

Ainslie: Is it a different musical headspace when you are freely improvising?

Sheldrake: Absolutely. That’s when I feel most alive, most present, most focused. It’s almost meditational. You have to say yes to anything that pops up. The second you say no, you’re done for. You have to absorb and incorporate everything, even if it’s a mistake. No is a resounding, clanging shut-down door and close windows feeling, and in that vulnerable improvising state it’s the last thing you want. In a compositional headspace, apart from anything else, I get racked by much more self-doubt because I have longer to think about things. Improvising there is no time to hang around. You say yes and move on. And I do miss that headspace because it’s the nearest you get to inspiration. Well out of your comfort zone where you find new ideas.

Ainslie: A lot of your music is inspired by nature, have you found any new ideas connecting with it deep in the countryside?

Sheldrake: Well, I’ve been completely immersed in birds. There’s a bird table right outside my window. When finishing “Wake Up Calls” [his latest album composed from birdsong], and being able to strap microphones into the hedge and listen as if I was in the hedge has connected me. This house I’m in now is off-grid, so I’ve noticed the seasons changing more, and it’s powered by a diesel generator. I have a battery-powered studio and solar panels, and there’s no central heating so every morning I have to chop wood, spending 30 percent of my energy just on keeping warm.

It’s healthy in some ways. So much of my time here has been taken up not with nature but with electricity. I say that, but also I have been enjoying the different rhythms of life, and thinking about where electricity and heat come from and how much we are using, constantly. I have to decide between working into the night or having power to work tomorrow, and where best to use the energy. Completely renegotiating my power relationship. But I’ve been incredibly grateful and very lucky to have this little cottage.

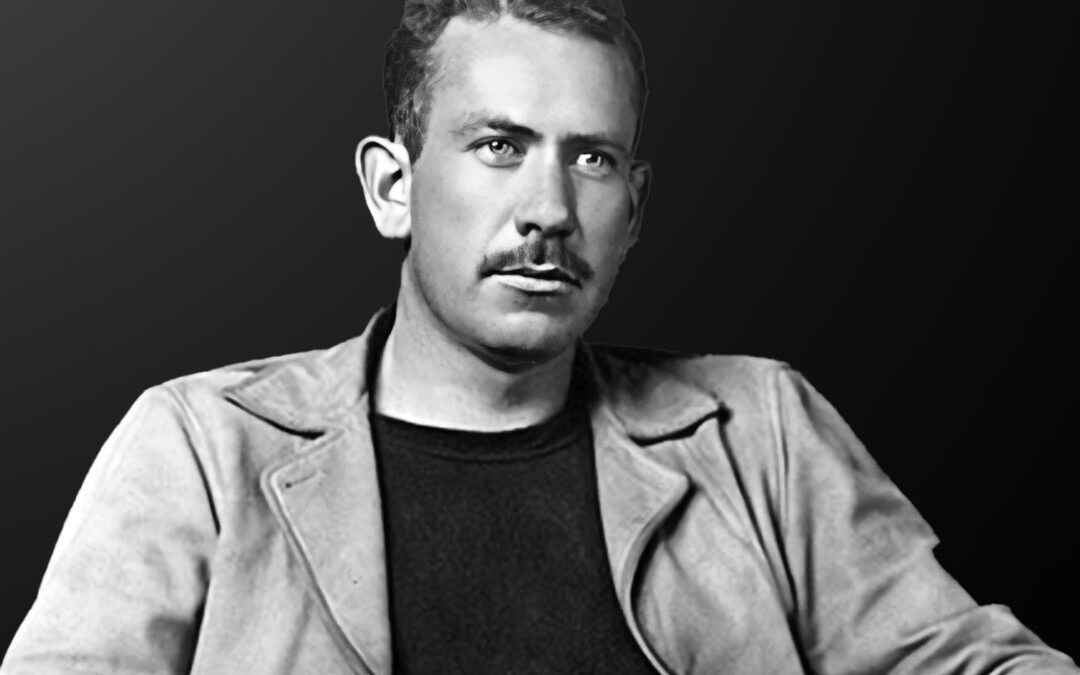

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of acclaimed author and local writer John Steinbeck, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1962. Much of Steinbeck’s fiction is set in Central California, particularly in the Salinas Valley and Monterey Bay area, which is near where we live. Steinbeck’s works often explored themes of fate and injustice, especially among the poor and downtrodden.

John Ernst Steinbeck was born in 1902 in Salinas, California. His father served as Monterey County Treasurer, and his mother was a schoolteacher, who had a passion for reading and writing. Steinbeck grew up in a small, rural valley along the Pacific coast. Both the valley and coast would later serve as settings for some of his most well-known novels.

When he was growing up, Steinbeck spent his summers working on nearby ranches, such as the Post Ranch in Big Sur. In 1919, Steinbeck graduated from Salinas High School. He then enrolled at Stanford University, where he studied English literature, although he never finished his degree.

In 1925, Steinbeck traveled to New York City, where he took odd jobs and started writing fiction, although he failed to get anything published. In 1928, he returned to California and worked as a tour guide and caretaker at Lake Tahoe, where he met the woman who became his wife. Steinbeck continued writing, and in 1929, his first novel, Cup of Gold, was published. It is the story of a swashbuckling pirate, who ruled the Spanish Main with his vicious outlaw activity.

In 1930, Steinbeck married Carol Henning in Los Angeles. Steinbeck attempted to earn a living by manufacturing plaster mannequins with friends, but this didn’t turn out to be a successful business venture, and they ran out of money six months later. Steinbeck and Henning moved back to Pacific Grove, where they lived in a cottage owned by his father just outside of Monterey. Henning became the model for the character Mary Talbot in Steinbeck’s novel Cannery Row.

Steinbeck’s parents gave him free housing, paper for his manuscripts, and loans that allowed him to write without having to look for work. The couple lived on fish and crabs gathered from the sea, and fresh vegetables from their garden, but still their money ran out. Then they lived on welfare, and “on rare occasions” they stole bacon from the local market.

Around this time, Steinbeck wrote a mystery novel called Murder at Full Moon, about a dangerous werewolf that was on the loose. Publishers rejected this book, and it remains unpublished to this day, as Steinbeck’s estate doesn’t want it released, despite pleas from many people who are eager to read it.

Between 1930 and 1933, Steinbeck produced three shorter works, The Pastures of Heaven, The Red Pony, and To a God Unknown. During this time, Steinbeck was a relatively obscure writer with little success, although he “never doubted that he would achieve greatness.”

During this period, Steinbeck met marine biologist Ed Ricketts, who became a close friend and mentor. Ricketts operated a biology lab on the coast of Monterey, selling biological samples of marine animals, and he became a proponent of ecological thinking. They shared a love of music and art, and the two had a deep bond. When Steinbeck became emotionally upset, Ricketts sometimes played music for him.

In 1935, Steinbeck published his novel Tortilla Flat, which was his first critical success, and won the California Commonwealth Club’s Gold Medal. The novel portrays the adventures of a group of poor, yet loyal friends, living in the Monterey region during the post-World War I era. The story focuses on their simple lives, camaraderie, and escapades, which were creatively expressed within the mythic structure of an Arthurian legend.

Next, Steinbeck began writing what was to become one of his most widely acclaimed novels, Of Mice and Men, which was published in 1937. This is a drama about the dreams of two migrant agricultural laborers in California, and it was adapted into a Hollywood film two years later, starring Lon Chaney Jr.

In 1939, Steinbeck followed this wave of success with the publication of his novel The Grapes of Wrath, which is often considered to be his greatest work. Set during the Great Depression, it’s the story of a poor family of farm workers who leave Oklahoma for California. It was controversial at the time that it was published, and from 1939 to 1941, it was banned in certain California public schools, because the Kern County Board of Supervisors claimed that it was obscene and misrepresented conditions in the county.

However, The Grapes of Wrath won both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize, as well as being prominently cited when Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1962. In 1940, The Grapes of Wrath was adapted as a Hollywood film, directed by John Ford, and starring Henry Fonda, who was nominated for the Best Actor Academy Award for the role. In 1942, Steinbeck’s novel Tortilla Flat was also adapted into a movie, starring Spencer Tracy. With some of the proceeds from this, Steinbeck built a summer ranch home in Los Gatos, California.

In 1945, Steinbeck’s novel Cannery Row was published. The novel, set in Monterey, also took place during the Great Depression. The story revolves around people living along a street with sardine canneries known as Cannery Row” The actual location that Steinbeck was writing about was named Ocean View Avenue at the time that he wrote the novel, but it was later renamed Cannery Row in honor of the book. A film version of Cannery Row was released in 1982, and a stage version in 1995.

During the last years of his life, Steinbeck remained an active and prolific writer, despite battling health issues. He continued to produce several notable works, including Travels with Charley: In Search of America, which chronicled his cross-country road trip with his poodle, Charley. Steinbeck also wrote America and Americans, a collection of essays that explored various aspects of American society and culture.

Steinbeck was also involved in political activism, speaking out against social injustices, and advocating for workers’ rights. Despite his declining health, Steinbeck’s literary contributions and commitment to addressing important societal issues continued until his passing. Steinbeck died in 1968, in New York City, at the age of 66.

Steinbeck’s boyhood home in Salinas is preserved and is open for tours. Nearby in Salinas is the National Steinbeck Center, a museum and memorial dedicated to Steinbeck, which was founded in 1983. In 2007, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger inducted Steinbeck into the California Hall of Fame. Today, when driving along U.S. Route 101 through Salinas, a large green sign announces that one is driving along the John Steinbeck Highway.

Some of the quotes that John Steinbeck is known for include:

I wonder how many people I’ve looked at all my life and never seen.

It’s so much darker when a light goes out than it would have been if it had never shone.

What good is the warmth of summer, without the cold of winter to give it sweetness?

A sad soul can kill you quicker, far quicker, than a germ.

You’ve seen the sun flatten and take strange shapes just before it sinks in the ocean. Do you have to tell yourself every time that it’s an illusion caused by atmospheric dust and light distorted by the sea, or do you simply enjoy the beauty of it?

I was born lost and take no pleasure in being found.

To be alive at all is to have scars.

When two people meet, each one is changed by the other, so you’ve got two new people.

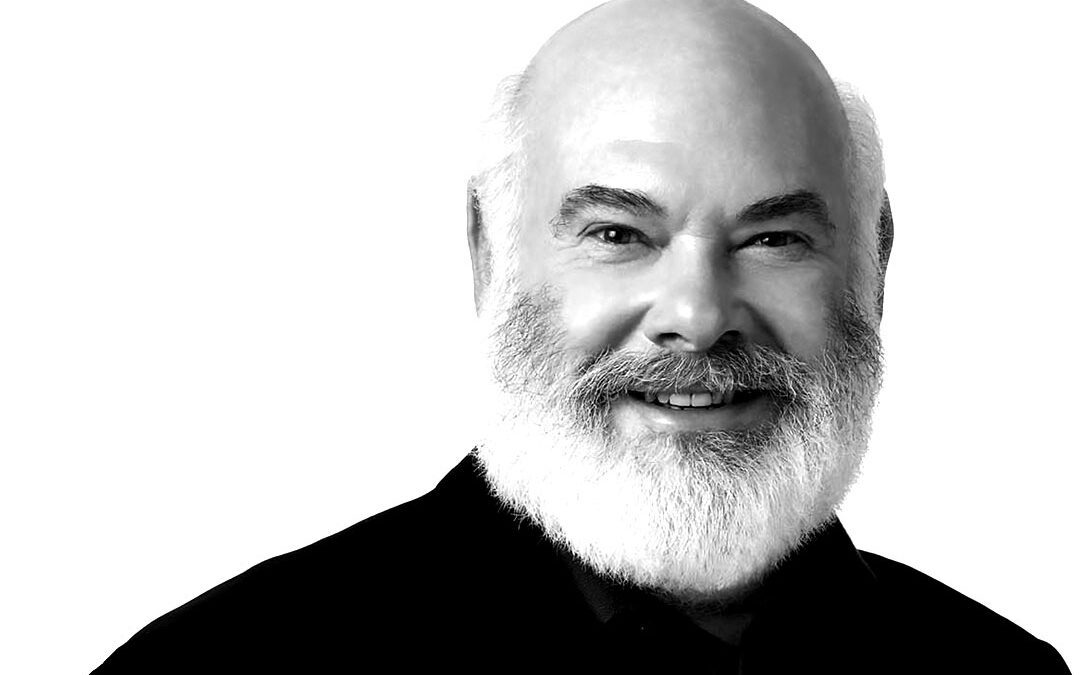

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of Andrew Weil, M.D., who is an internationally recognized expert on Integrative Medicine, which combines the best therapies of conventional and alternative medicine. Weil’s lifelong study of medicinal herbs, mind-body interactions, and alternative medicine has made him one of the world’s most trusted authorities on unconventional medical treatments, as his sensible, interdisciplinary medical perspective strikes a strong chord in many people.

Andrew Thomas Weil was born in Philadelphia in 1942, and he grew up as an only child. His parents operated a hat-making store and were Reform Jews. In 1959, Weil graduated from high school, and he was awarded a scholarship that allowed him to study abroad for a year, living with families in India, Thailand, and Greece. As a teenager, he was deeply influenced by Aldous Huxley’s book The Doors of Perception, about the author’s visionary experiences.

In 1960, Weil was admitted to Harvard University, where he studied biology, with a concentration in ethnobotany. Weil had an interest in psychoactive drugs, and while at Harvard, he met with Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (Ram Dass), and wrote about their research, as well as some of their extracurricular exploits, in a series of articles for the school paper, The Harvard Crimson, which stirred up considerable controversy.

In 1964, Weil graduated “cum laude,” and he entered Harvard Medical School, “not to become a physician but rather simply to obtain a medical education.” Weil received his medical degree in 1968 after the Harvard faculty threatened to withhold it because of a controversial cannabis study that he helped conduct in his final year.

After Weil received his medical degree, he moved to San Francisco and completed a one-year internship at Mount Zion Hospital. During this time in San Francisco from 1968 to 1969, Weil volunteered at the Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic. Weil then spent a year attending a program at the National Institute of Health, before taking a position at the National Institute of Mental Health to pursue his interest in psychoactive drugs.

In 1971, Weil experienced opposition to his line of inquiry at the National Institute of Mental Health, so he left for his home in rural Virginia, where he began to experiment with different health-enhancing practices— such as Yoga, meditation, and a vegetarian diet— and he began writing a book. In 1972, his book The Natural Mind was published, which is an investigation into the relationship between drugs and higher consciousness, and has sold over 10 million copies to date.

From 1971 to 1984, Weil was on the research staff of the Harvard Botanical Museum, where he conducted investigations into medicinal and psychoactive plants. Then from 1971 to 1975, as a Fellow of the Institute of Current World Affairs, Weil traveled throughout Central and South America, collecting information and specimens for this research. These explorations— where he not only studied plants but indigenous peoples, their medicine, and pharmacology—were to have a profound effect on Weil’s medical career.

In 1994, Weil founded the Arizona Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine in Tucson, where he serves as director to this day. Weil is also the founder of True Food Kitchen, a restaurant chain serving meals on the premise that “food should make you feel better.” There are currently 44 restaurants in this chain.

Weil has had a life-long talent for blending the conventional with the unconventional, and he has been interested in altered states of consciousness, and how the mind affects health, since before he began studying medicine. He has written extensively about this interest, and about how his early psychedelic experiences profoundly influenced his views on medicine. Because of this interest in altered states of consciousness, Weil has been honored by having a psychedelic mushroom named after him— Psilocybe Weilii— which was discovered in 1995.

Weil is the author of more than twenty popular books, including The Marriage of the Sun and Moon, From Chocolate to Morphine, Natural Medicine, Spontaneous Healing, and Healthy Aging. In addition to being the Director of the Program in Integrative Medicine at the University of Arizona’s College of Medicine, Weil also holds appointments as a Clinical Professor of Medicine, Professor of Public Health, and the Lovell-Jones Professor of Integrative Rheumatology.

Weil has been a frequent guest on many television shows, such as Larry King Live, Oprah, and The Today Show. He has also appeared in three videos featured on PBS: Spontaneous Healing, Eight Weeks to Optimum Health, and Healthy Aging. Many of his books are New York Times bestsellers, and he has appeared on the cover of Time magazine twice, in 1997 and again in 2005. USA Today” said, “Clearly, Dr. Weil has hit a medical nerve,” and The New York Times Magazine said, “Dr. Weil has arguably become America’s best-known doctor.”

I interviewed Andrew Weil in 2006. We talked about some of the most important lessons that physicians aren’t being taught in medical school, why conventional Western medicine needs to be more open-minded about alternative medical treatments, and how the mind and spirituality affect health. This interview appears in my book Mavericks of Medicine. Here is an excerpt from our conversation:

David: What role do you see the mind and consciousness playing in the health of the body?

Andrew Weil: I think it’s huge. This is an area that I’ve been interested in, I think, since I was a teenager— long before I went to medical school— and a lot of my early work was with altered states of consciousness and psychoactive drugs. I reported a lot of things that I saw about how physiology changed drastically with changes in consciousness. I just reviewed a paper from Japan; one of the authors is a doctor I know. This is a group of people looking at how emotional states affect the genome. They have shown, for example, that laughter can affect gene expression in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Now that’s really interesting stuff, and I think that this is the type of research that is generally not looked at here. I think that our mental states— our states of consciousness— have a profound influence on our bodies, and even our genes. And I think they have a lot to do with how we age.

David: What role do you think that spirituality plays in health?

Andrew Weil: Again, I think, large, but it’s hard to define spirituality. For me, I make a very sharp distinction between spirituality and religion. Religion is really about institutions, and for me, spirituality is about the nonphysical, and how to access that and incorporate it into life. In “Eight Weeks to Optimum Health,” I gave a lot of suggestions each week about things that people can do to improve or raise spiritual energy, and they are things that at first many people might not associate with spirituality. But they were recommendations like having fresh flowers in your living space and listening to pieces of music that elevate your mood. Some of the other suggestions included spending more time with people in whose company you feel more optimistic and better, and spending time in nature. I think that I would put all of these in the realm of spiritual health.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of American poet Walt Whitman. Although Whitman is now considered one of the most influential poets in American history, his work was controversial during his lifetime, particularly his collection Leaves of Grass, which some critics described as “obscene” because of its overt sexuality.

Walter Whitman, Jr. was born in Huntington, New York in 1819. He was the second of nine children. Both of his parents were Quakers with little education. Whitman’s father was a carpenter, and he was nicknamed “Walt” to distinguish him from his father, Walter Whitman, Sr. At the age of four, he moved to Brooklyn with his family, and they struggled economically.

Whitman generally described his childhood as being “restless and unhappy,” due to his family’s financial difficulties, but he later recalled one particularly happy moment. During a celebration in 1825 at a library in Brooklyn, the Revolutionary War hero General Marquis de Lafayette lifted the young Whitman into the air and kissed his cheek. Years later, Whitman worked at that same institution as a librarian.

Whitman attended public schools in Brooklyn up until the age of 11, after which he sought employment to assist his family. He worked as an attorney’s assistant, had clerical jobs with the federal government, and was a newspaper printer. In 1831, Whitman took a job as the apprentice of Alden Spooner, who was the editor of the weekly newspaper The Long Island Star. Whitman spent much time at his local library, he joined a town debating society and began attending theater performances.

It was around this time that Whitman published some of his earliest poetry in The New York Daily Mirror. In 1835, he worked as a typesetter in New York City, and the following year he moved back in with his family in Long Island, where he taught intermittently at various schools until 1838. Whitman wasn’t happy teaching, and he decided to start his newspaper, which he called the Long Islander. Whitman did everything for the paper; he was the reporter, publisher, editor, pressman, and distributor. He even provided home delivery. After ten months he sold the publication.

Whitman continued writing. During the 1840s, he contributed freelance fiction and poetry to various periodicals, such as Brother Jonathan magazine. In 1842, Whitman wrote a novel called Franklin Evans about the temperance movement. In 1852, he serialized a mystery novel titled Life and Adventures of Jack Engle, and in 1858, he published a self-help guide called Manly Health and Training under the pen name Mose Velsor.

In 1855, Whitman self-published the first edition of his landmark poetry book Leaves of Grass, which he had been working on for around five years. This was his magnum opus. The book was strongly endorsed by Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote a five-page letter to Whitman praising the work, which was printed in the New York Tribune, and this helped to stir up considerable interest in the book. Leaves of Grass, which was widely distributed, quickly became controversial, due to claims that some of the material in the poems was sexually offensive.

On more than one occasion, Whitman was fired or denied work because people were offended by the sexual imagery in his poetry. Although Whitman is largely considered to be gay or bisexual by biographers, his actual sexual orientation remains a mystery, and is debated. Whitman’s sexual orientation has been generally assumed based on his poetry, as he never publicly addressed this.

In 1856, the second edition of Leaves of Grass was published, with 20 additional poems. Then further revised editions were published in 1860, 1867, and five more times throughout Whitman’s life. Whitman continued to edit and revise Leaves of Grass until his death. The title of the poetry collection is an example of Whitman’s self-deprecating wordplay and humor. It’s a pun and meant to have multiple meanings. Leaves referred to the “sheets of paper in a book,” and “grass” was used to denote “things that weren’t of much value.” In other words, Leaves of Grass means “pages of little value.”

Whitman is often referred to as the “father of free verse poetry.” The poems in Leaves of Grass do not rhyme or follow standard rules for meter and length. The collection of loosely connected poems represents a celebration of Whitman’s philosophy of life, as well as his praise of nature and the human body. The first edition only contained twelve poems and the final edition contained over 400. The last version of the book was published in 1892, and is referred to as the “deathbed edition.”

Whitman’s poetry is intertwined with America’s past, and many scholars consider him to be an important figure in understanding our country’s history, because of his ability to write in a singularly American character. During the American Civil War, Whitman went to Washington, D.C. where he volunteered to work in hospitals caring for the wounded, and when President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated Whitman wrote a highly influential poem about him called O Captain! My Captain. According to poet Ezra Pound, Whitman is “America’s poet… He is America,” and Whitman said, “The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem.”

During his lifetime, groups of disciples and admirers of Whitman formed, who would meet to read and discuss his poetry. One group subsequently became known as the Bolton Whitman Fellowship, or Whitmanites” and its members held an annual Whitman Day celebration around the poet’s birthday on May 31st.

Whitman died in 1892, at the age of 72. He is buried at the Harleigh Cemetery in Camden, New Jersey.

In 1940 a U.S. postage stamp was created in Whitman’s honor. His poetry has been set to music by more than 500 composers, and his vagabond lifestyle was adopted by the Beat culture and its writers, such as Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac in the 1950s and 1960s. Here in my hometown, at the Bookshop Santa Cruz, there’s a life-size replica of Gabriel Harrison’s famous drawing of Whitman standing at the front entrance of the store as its mascot.

Some of the quotes that Walt Whitman is known for include:

Keep your face always toward the sunshine— and shadows will fall behind you.

Re-examine all you have been told. Dismiss what insults your soul… Whatever satisfies the soul is truth.

The art of art, the glory of expression, and the sunshine of the light of letters, is simplicity.

“I do not ask the wounded person how he feels, I myself become the wounded person.

Pointing to another world will never stop vice among us; shedding light over this world can alone help us.

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

I am satisfied … I see, dance, laugh, sing… I exist as I am, that is enough.

I believe a leaf of grass is no less than the journeywork of the stars.

In the faces of men and women, I see God.

Carolyn and I have appreciated the work of French painter, sculptor, and printmaker Edgar Degas, who is well-known for his pastel drawings and oil paintings. Degas was prominent among the Impressionists, although he considered himself to be a “realist,” and his artwork is intimately intertwined with dance, as more than half of his work depicts female dancers. Degas helped to bridge the gap between traditional academic art and the radical art movements of the early 20th century.

Edgar Degas was born in Paris, France in 1834. His father was a banker, his mother an opera singer, and his family was moderately prosperous. Degas was the oldest of five children and his mother died when he was 13. Degas was largely raised by his father and several unmarried uncles. In 1845, Degas began his education at a leading boy’s school in central Paris, the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, where he received a conventional classical education. Degas began to paint early in life, and he turned a room in his home into an artist’s studio.

In 1853, Degas graduated from the Lycée with a degree in literature. Then, because of his father’s expectations, he enrolled in law school at the University of Paris, although he lacked the motivation to follow through with this, and applied little effort to his studies. In 1855, Degas was admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he studied drawing, and his father then encouraged his artistic pursuits, taking him frequently to museums.

In 1856, Degas abandoned his education in Paris and left for Italy, where he studied painting and sculpture for three years. While he was there, Degas filled up notebooks with many sketches of historic buildings, people’s faces, landscapes, and quick pencil copies of oil paintings that he admired, as well as notes and reflections.

In 1859, Degas returned to Paris, set up a studio, and began work on several “history paintings,” a genre of painting defined by its subject matter rather than a particular artistic style or specific period. History paintings often realistically depict a moment in a narrative story. Although Degas is regarded as one of the founders of Impressionism, he preferred to be called a “realist,” as he generally aimed to represent his subject matter truthfully and naturally. Between 1860 and 1865, Degas exhibited his work annually at The Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

In 1870, Degas enlisted in the National Guard, due to the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, and this left him little time for painting during this period. After the war, Degas traveled to New Orleans, where he had relatives, and he stayed for several months. During this time, Degas produced several paintings, many depicting family members.

One of the paintings that Degas created during his time in New Orleans, A Cotton Office in New Orleans, was purchased by the Pau Museum in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of France. This was the only work by Degas that was purchased by a museum during his lifetime. In 1873, when Degas returned to Paris, his father died, and his brother had accumulated enormous business debts, so Degas was forced to sell the house and art collection that he had inherited, and he used that money to pay off his brother’s debts. This now meant that Degas was completely dependent on the sales of his artwork for income.

Degas became disenchanted with The Salon and instead joined up with a group of young artists who were organizing an independent exhibiting society, becoming one of its most important core members. This group became known as the Impressionists, and between 1874 and 1886 they held eight art exhibitions. Degas showed his work in all of them, except one, and he had a leading role in helping to organize the exhibitions. However, Degas disliked being associated with the term “Impressionist,” which the press had coined and popularized, and he insisted on using non-Impressionist artists’ work in the Impressionist exhibitions. This resulted in conflicts between the artists, and the group disbanded in 1886.

Although Degas referred to himself as a “Realist” or “Independent,” like the Impressionists he also sought to capture “fleeting moments in the flow of modern life.” However, he didn’t like painting landscapes outdoors like the Impressionists and instead preferred painting in theaters and cafes that were illuminated by artificial light. Degas was particularly intrigued by classical ballet, and the movement of female dancers, which are the subject of many of his paintings.

The sale of Degas’ artwork helped to improve his financial situation, and he was able to begin building up his art collection, acquiring the works of many old masters that he admired, such as Pissarro, Cézanne, Gauguin, and van Gogh. In the late 1880s, Degas developed a passion for creating with other media, such as photography and engraving. He photographed many friends and dancers, and some of the photos were used as a reference for his drawings and paintings.

Throughout his life, Degas worked with many different types of artistic tools. His drawings include examples in pen, ink, charcoal, chalk, and pastel, often in combination with one another, and his paintings were done in oils, watercolor, gouache, distemper, and metallic pigments on a wide variety of surfaces, such as silk, ceramic, tile, and wood panel, in addition to many varieties of canvas textures.

Degas did work in sculpture too, using wax and other materials to make modest statuettes of horses and dancers. In one of his sculptures at the Impressionist Exhibition of 1881, Degas incorporated an actual tutu, ballet slippers, a human-hair wig, and a silk ribbon to enhance visual realism.

As the years went by, Degas became progressively more and more isolated, perhaps due to his belief that “a painter could have no personal life.” After 1890, Degas’ eyesight, which had troubled him for much of his life, deteriorated further. He spent the last years of his life, nearly blind and depressed, although he continued working in pastel until the end of 1907, and is believed to have continued making sculptures as late as 1910. Degas stopped working in 1912 when the impending demolition of his longtime residence forced him to move to new quarters.

Degas died in 1917 at the age of 83. After Degas’s death, the enormous wealth of his output was revealed in a succession of public sales in Paris between 1918 and 1919. Thousands of his previously unexhibited works were sold. After his death, Degas’ reputation steadily grew, and his work began selling for high amounts, with prices ranging from $4,000,000 to $41,610,000. Degas’s work also began to enter major museums, and today can be viewed at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, and the Getty Villa in Malibu, California.

Some of the quotes that Edgar Degas is known for include:

Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.

Muses work all day long, and then at night get together and dance.

A painting requires a little mystery, some vagueness, and some fantasy. When you always make your meaning perfectly plain you end up boring people.

Only when he no longer knows what he is doing does the painter do good things.

Art critic! Is that a profession? When I think we are stupid enough, we painters, to solicit those people’s compliments and to put ourselves into their hands! What shame! Should we even accept that they talk about our work?

Painting is easy when you don’t know how, but very difficult when you do.

I should like to be famous and unknown.

Carolyn and I have admired the work of American painter Jackson Pollock, who was a leading figure in the abstract expressionism art movement, which was characterized by freely associative painting styles that helped the art world to redefine what a painting could be. Pollock is most well-known for developing the “drip technique,” a painting method that involves dripping, pouring, or splashing paint onto a horizontal surface, enabling the artist to paint his or her canvas from multiple angles. Pollock’s revolutionary work influenced many subsequent art movements that followed abstract expressionism.

Paul Jackson Pollock was born in Cody, Wyoming in 1912. His father, who was of Scottish-Irish descent, was a farmer and land surveyor for the government. Pollock’s mother came from an Irish family with a heritage of weavers, and she made and sold dresses. Pollock’s family left Wyoming when he was 11 months old, and he grew up in Arizona and California. Pollock’s childhood wasn’t very stable; his family moved nine times in the next 16 years, and in 1928 Pollock was expelled from two high schools for being a “troublemaker.”

In 1928, Pollock enrolled at the Manuel Arts School in Los Angeles, where he met painter and illustrator Frederick Schwankovsky, who gave him some training in drawing and painting and encouraged his interest in metaphysical and spiritual literature. Schwankovsky was a member of the Theosophical Society and was friends with Jiddu Krishnamurti. These early spiritual explorations may have influenced Pollock, as in subsequent years he embraced the theories of Swiss psychologist Carl Jung and the notion of unconscious imagery being expressed in his painting.

In 1930, Pollock moved to New York City, where his older brother was living, and he studied drawing, painting, and composition at the Art Students League. In 1936, Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros introduced Pollock to the use of liquid paint at an experimental workshop, and he later used paint pouring as one of his painting techniques. During this time Pollock’s painting style was part of the regionalism movement that depicted realistic scenes, and his style slowly began to become more abstract.

Around this time, Pollock began drinking too much. In 1937, he began treatment for a problem with alcoholism by undergoing Jungian psychotherapy. In 1938, he suffered a nervous breakdown, which caused him to be institutionalized for about four months, and his treatment involved being engaged with his art. Pollock was encouraged to make drawings and to see Jungian concepts and archetypes expressed in his paintings, as a way of exploring his unconscious mind.

From 1938 to 1942, Pollock found work as an easel painter with the Federal Arts Project, a federal program that helped struggling artists find employment during the Great Depression. In the early 1940s, Pollock moved to Springs, New York, and began developing his “drip” technique, with his canvases laid out on the studio floor. Pollock’s technique typically involved pouring paint straight from a can or along a stick onto a canvas lying horizontally on the floor.

In 1942, Pollock met the artist Lee Krasner at a gallery exhibition. They became romantically involved, influenced one another’s art, and in 1945 the couple was married. Krasner had extensive knowledge and training in modern art, and she introduced Pollock to many collectors, critics, and other artists who would further his career.

In 1943, Pollock signed a gallery contract with Peggy Guggenheim, and he did his first wall-sized work, a huge 8-by-20-foot abstract oil painting titled Mural. The painting was commissioned for the entrance hall of Guggenheim’s townhouse in NYC. In the foreword to the exhibition catalog, a New York Times reviewer described Pollock’s creativity as “…volcanic. It has fire. It is unpredictable. It is undisciplined. It spills out of itself in a mineral prodigality, not yet crystallized.” Mural represents Pollock’s “breakthrough into a totally personal style in which compositional methods, and energetic linear invention, are fused with the Surrealist free association of motifs and unconscious imagery.”

Between 1947 and 1950 was Pollock’s “drip period,” when he produced some of his most famous abstract paintings. The process involved pouring or dripping paint onto a flat canvas in stages, often alternating weeks of painting with weeks of contemplating, before he finished a canvas. A whole series of famous paintings were created during this period, such as Full Fathom Five, Lucifer, and Summertime. Pollock also created more mural-sized canvases, such as One, Autumn Rhythm, and Lavender Mist.

In 1949, Life magazine did a four-page spread of Pollock’s work, and the accompanying article suggested that he might be the “greatest living painter” in the United States. Then, at the peak of his fame, Pollock abruptly abandoned the drip style of painting. He began attempting to balance abstraction with depictions of figures in his paintings and used darker colors.

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Pollock had one-man shows of new paintings nearly every year in New York. His work was handled by Peggy Guggenheim through 1947, then by the Betty Parsons Gallery from 1947 to 1952, and then by the Sidney Janis Gallery from 1952 onward.

After 1953, Pollock’s health began to deteriorate, and his production began to wane, but he still produced a number of important paintings in his final years, such as White Light and Scent. In 1956, Pollock died in a single-car crash while under the influence of alcohol.

Four months after his death, Pollock was given a memorial retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Pollock did not profit financially from his fame. During his lifetime, Pollock never sold a painting for more than $10,000 and was often hard-pressed for cash, but in 2016, his painting “umber 17A sold for $200 million. Now considered an “iconic” master of mid-century Modernism, his work influenced the American art movements that immediately followed Abstract Expressionism — such as Happenings, Pop Art, Op Art, and Color Field painting.

One of the things that I’ve found most intriguing about Pollock’s art is how it continues to be controversial, almost seven decades after his death. It’s not uncommon to hear people say“It’s just the flinging of paint!” This leads me to believe that Pollock’s critics, be they of his time or ours, are largely wrong — for it’s hard for me to understand why people would get so worked up over an artist, almost 70 years after his death unless there’s something in his work that truly matters.

Some of the quotes that Jackson Pollock is known for include:

Painting is self-discovery. Every good artist paints what he is.

New needs need new techniques. And the modern artists have found new ways and new means of making their statements… the modern painter cannot express this age, the airplane, the atom bomb, the radio, in the old forms of the Renaissance or of any other past culture.

On the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting.

The secret of success is… to be fully awake to everything about you.

There is no accident, just as there is no beginning and no end.

The painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through.

When I’m painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing. It’s only after a get acquainted period that I see what I’ve been about. I’ve no fears about making changes for the painting has a life of its own.

Modern artists unravel inner universes, expressing energy, motion, and latent forces.