Carolyn Mary Kleefeld – Contact Us

Please fill out form as completely as possible so we can contact you regarding your request.

Carolyn urged me to read the Autobiography of a Yogi for years before I finally read it. However, after reading Yogananda’s spiritual classic it became one of my favorite books and I’ve reread it numerous times. It’s an amazing story. There’s no other book quite like it; it’s a wildly entertaining page-turner, overflowing with magnificent tales of incredible miracles and profound Eastern wisdom.

Born in India in 1893, Paramahansa Yogananda was a Hindu monk, yogi, and beloved guru, who introduced millions of people to the teachings of meditation and Kriya Yoga and is considered one of the pioneering fathers of Yoga in the West.

In India, Yogananda was a chief disciple of the Bengali Yoga guru Swami Sri Yukteswar Giri. While meditating one day in 1920 at his Ranchi school, Yogananda had a vision where he saw a multitude of American faces pass before his mind’s eye. He took this vision as a sign that he would travel to America, and soon afterward he accepted an offer to come to speak in Boston.

Yogananda left for the United States that year to spread the teachings of Yoga in the West, to demonstrate the unity between Eastern and Western religions, and to help promote a balance between Western material growth and Indian spirituality. Yogananda’s talk in Boston was well received and he soon embarked on a cross-country speaking tour. Thousands of people came to his lectures, and he attracted a number of celebrity followers, including Clara Clemens Gabrilowitsch, Mark Twain’s daughter.

In 1925 Yogananda founded the Self-Realization Fellowship in Los Angeles, which became the spiritual and administrative center of his growing international organization, and it continues to disseminate his teachings to this day. Yoganada’s worldwide influence has been quite substantial; by 1952, his organization had over 100 centers in both India and the U.S., and today they have groups in nearly every major American city.

Yogananda’s book, Autobiography of a Yogi, which was published in 1946, has remained continuously in print, sold over four million copies, and has been translated into over fifty languages. Former Apple CEO Steve Jobs loved Yogananda’s book so much that he ordered 500 copies of it for his own memorial, so each guest could take home a copy.

Yogananda was the first prominent Indian citizen to be hosted in the White House, by President Calvin Coolidge in 1927, and the Indian government released a commemorative stamp in his honor in 1977. Yogananda’s great popularity led to him being dubbed “the 20th century’s first superstar guru” by the Los Angeles Times in 2006.

Some quotes that Yogananda is remembered for include:

Live each moment completely and the future will take care of itself. Fully enjoy the wonder and beauty of each moment.

Be as simple as you can be; you will be astonished to see how uncomplicated and happy your life can become.

You may control a mad elephant; You may shut the mouth of the bear and the tiger; Ride the lion and play with the cobra; By alchemy you may learn your livelihood; You may wander through the universe incognito; Make vassals of the gods; be ever youthful; You may walk in water and live in fire; But control of the mind is better and more difficult.

Kindness is the light that dissolves all walls between souls, families, and nations.

Forget the past, for it is gone from your domain! Forget the future, for it is beyond your reach! Control the present! Live supremely well now! This is the way of the wise…

Dylan Thomas was a brilliant Welsh poet and writer whom Carolyn and I both admire, who has been acknowledged as one of the most important poets of the 20th century. His iconic poems— which include such masterpieces as “Do not go gentle into that good night” and “And death shall have no dominion,” are known for their acute use of lyricism, imagery, and emotion. Although influenced by the Romantic tradition, Thomas’ refusal to align with any literary group or movement has made his work difficult to categorize and ever more important.

Self-described as a “roistering, drunken and doomed poet,” Dylan Thomas lived a short life; he died at the age of 39, but packed a lot of creative output into those years. Thomas dropped out of school at sixteen, in 1930, to become a junior reporter for the South Wales Daily Post, but left this job two years later so that he could concentrate full-time on his poetry. Thomas wrote 200 poems between 1930 and 1934 when he was in his late teens and had nine volumes of poetry and ten volumes of prose published. Even though Thomas was recognized as a great poet during his lifetime, he had difficulty earning a living as a writer and augmented his income with reading tours and radio broadcasts.

Dylan Thomas became a pop star among poets, known for his dramatic poetry readings, and he had as many fans of his live performances as readers of his published poems. Many people have been inspired by his powerful poetry. Poet Sylvia Plath has said that Thomas was one of her most important influences, and singer-songwriter Bob Zimmerman renamed himself “Bob Dylan,” because he was so inspired and influenced by Dylan Thomas. Lovers of Thomas’ extraordinary work celebrate every year on May 14th, which is International Dylan Thomas Day.

Our beloved friend Peter Thabit Jones, who is a scholar and poet, wrote a wonderful book, Dylan Thomas: Walking Tour of Greenwich Village. Jones’s book serves as a self-guided tour of ten places in Greenwich Village, New York, associated with Thomas, and it contains a foreword by Hannah Ellis, the granddaughter of Dylan Thomas.

Some quotes that Dylan Thomas is remembered for include:

When one burns one’s bridges, what a very nice fire it makes.

Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

A good poem is a contribution to reality. The world is never the same once a good poem has been added to it. A good poem helps to change the shape of the universe, helps to extend everyone’s knowledge of himself and the world around him.

I first started enjoying Anaïs Nin’s erotic stories when I was in my early twenties, and I was intrigued by the encounters with Henry Miller that she described in her diaries. (Henry Miller is another author that Carolyn and I both admire, and who will be the subject of a future profile.) When I first met Carolyn we discussed Nin’s writings, and I was most interested to learn that Carolyn had met and corresponded with Nin years earlier.

Born in France, Anaïs Nin lived from 1903 to 1977 in major European and American cities during culturally vibrant times, where she recorded her personal encounters with many brilliant and creative minds. Nin spent her early years growing up in Spain and Cuba and then lived in Paris, New York, and Los Angeles. Nin was known for her prolific and varied writings that included celebrated essays, novels, and short stories, as well as her seven published volumes of diaries, and revolutionary volumes of erotica.

When Nin was in her late twenties, she developed a strong interest in psychoanalysis and studied it in depth— with René Allendy and Otto Rank— both of whom also became lovers, as she recounts in her diaries. Nin famously kept detailed journals of her private thoughts and intimate relationships, from the age of eleven until the end of her life. Many of these diaries were published during her lifetime and remain in print to this day. The revealing diaries that she kept included descriptions of her personal relationships with many well-known literary figures and intellectuals, such as John Steinbeck and Gore Vidal, and have unique historical value.

Some of the quotes that Anaïs Nin is remembered for include:

We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.

And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom.

Life shrinks or expands in proportion to one’s courage.

Nin has been lauded by critics for being one of the first and finest writers of women’s erotica, and much of her passionate, taboo-breaking work was published posthumously amid renewed critical interest in her life and work that continues to this day.

Carolyn and I have celebrated numerous events at the Henry Miller Memorial Library in Big Sur over the years, and she has had many poetry readings there. Located on the Pacific Coast Highway, and nestled among the glorious redwood trees, this beautiful library documents the life of the late author and artist Henry Miller, and also serves as a performance venue and art gallery, where local artists can exhibit their work. It’s a magical place that is cherished by the local community and loved by the many international visitors passing through Big Sur, where Henry Miller is remembered as a legendary figure.

Henry Miller is another brilliant writer whom Carolyn and I have both admired. His semi-autobiographical novel Tropic of Cancer was a creative whirlwind that blew my mind apart when I first read it in my early twenties. Miller’s writing was a revolution; he created his own unique literary style, combining actual events from his life, with fantasies and exaggerations, as well as explicit sexuality, philosophical reflections, surrealist free association, Eastern philosophy, and mysticism.

Some of Miller’s most famous books, which were based upon his experiences in New York and Paris— such as Tropic of Cancer (first published in 1934), and Black Spring — were controversial when they were first published, largely due to their explicit sexual descriptions, and were officially banned in the United States until 1964. Tropic of Cancer was published in 1961 by the Grove Press in the U.S., challenging the ban. This led to obscenity trials, resulting in the Supreme Court’s official lifting of the ban in 1964. However, Miller’s banned books had been smuggled into the U.S. prior to 1961, and he built an underground reputation in the States before the ban was officially lifted.

Miller’s later works were less sexually explicit, more philosophical, and often critical of consumerism in America— such as The Air-Conditioned Nightmare, which was published in 1945, and also introduces elements of Hindu philosophy. Miller’s impressionist travelogue The Colossus of Maroussi, about his nine months in Greece in 1939, is frequently considered his best book. Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch, another favorite, was published in 1957 and is a collection of wonderful stories about his time in Big Sur, and the extraordinary people that he met.

Some quotes that Henry Miller is remembered for include:

The aim of life is to live, and to live means to be aware, joyously, drunkenly, serenely, divinely aware.

The one thing we can never get enough of is love. And the one thing we never give enough of is love.

I need to be alone. I need to ponder my shame and my despair in seclusion; I need the sunshine and the paving stones of the streets without companions, without conversation, face-to-face with myself, with only the music of my heart for company.

Develop an interest in life as you see it; the people, things, literature, music – the world is so rich, simply throbbing with rich treasures, beautiful souls and interesting people. Forget yourself.

Miller was a powerhouse of creative energy. In addition to his revered literary abilities, Miller was also an accomplished artist who produced several thousand watercolor paintings and published several books of his artwork.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to interview Henry Miller, although I would have loved to; he died years before I started doing interviews.

Photo: ©Globe Photos/ZUMAPRESS.com/Alamy

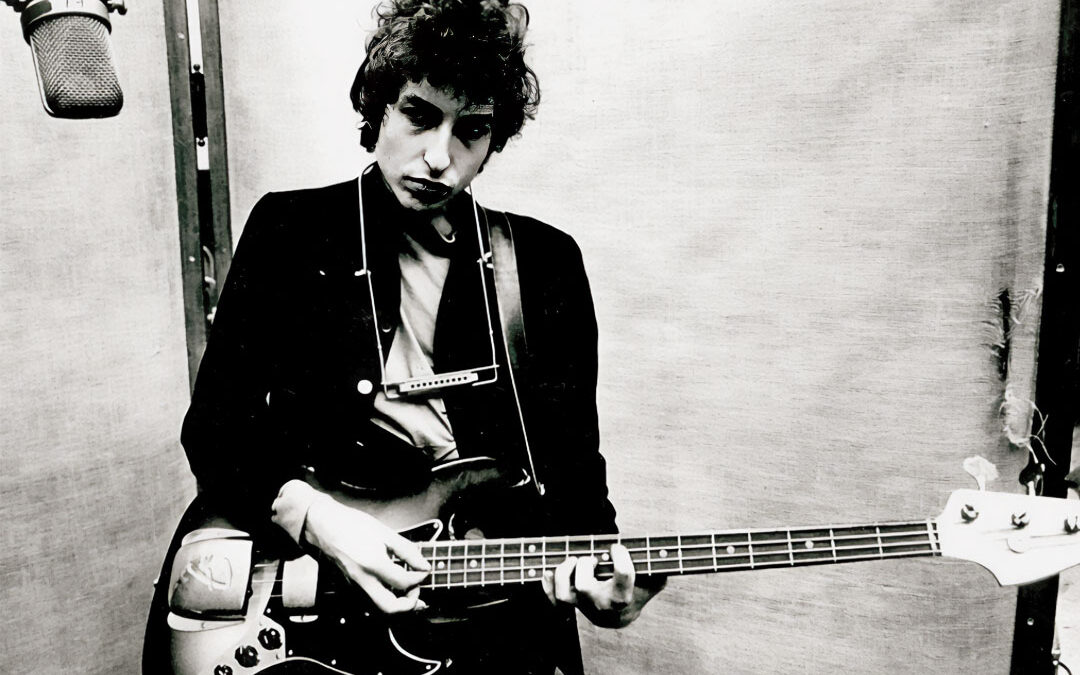

Bob Dylan is often regarded as one of the greatest singer-songwriters of all time, and he has been a favorite musician of both Carolyn and mine for decades. With a prolific career spanning more than 60 years, Dylan has profoundly influenced music and popular culture in many ways, with his unique poetic gifts, acute political awareness, and natural storytelling abilities.

Born Robert Allen Zimmerman in 1941, and raised in Hibbing, Minnesota, Dylan’s grandparents were Jewish refugees from Russia and Lithuania, who arrived in the United States around the turn of the 20th Century.

While attending Hibbing High School, Dylan performed in several bands. He played cover songs by Elvis Presley and Little Richard in a band called The Golden Chords, and his performance of Rock and Roll is Here to Stay with Danny & the Juniors at his high school talent show was so loud that the principal cut the microphone during mid-performance.

In 1959 Dylan enrolled at the University of Minnesota, where he studied American folk music. Dylan started performing at coffee shops around this time, and he began introducing himself as “Bob Dylan” to give himself anonymity and recreate his persona. He used various aliases initially in his career, such as “Elston Gunn” and “Robert Dillion,” but Bob Dylan is the one that stuck.

In 1960, after his first year in college, Dylan dropped out of school, and a year later he traveled to New York City where he went to perform, and he visited his music idol Woody Guthrie, who was seriously ill in the hospital. In 1961 Dylan began playing in clubs around the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan and often accompanied other folk musicians on the harmonica. When Dylan was 19, he performed at the Café Wha? in Greenwich Village, which was started by our beloved friend Jai Italiaander and her husband.

That same year Dylan played the harmonica on an album by Carolyn Hester, which brought his work to the attention of the album’s producer, who signed Dylan on to Columbia Records. Dylan’s first album, Bob Dylan, consisted of traditional folk, blues and gospel songs, with only two original compositions. The album sold just enough copies to break even, but Dylan was starting to become better known.

Dylan’s second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, was released in 1963, and his music— often labeled as “protest songs,” with lyrics that questioned the social and political status quo— became more popular. This album contained his well-known song Blowin’ in the Wind, which was partly derived from the melody of a traditional slave song. Along with the politically charged The Times They Are a Changin, these songs became anthems for the antiwar and civil rights movements of the 1960s.

Dylan’s revolutionary third album Bringing it all Back Home, which was released in 1965, featured his first recordings using electric instruments, and with free-association lyrics that were reminiscent of beat poetry. Using electric instruments with folk music caused some controversy within the folk music establishment, but Dylan’s popularity continued to soar. Dylan has since gone on to sell more than 125 million records, making him one of the bestselling musicians of all time. To date, Dylan has released 39 studio albums, 95 singles, and 15 live albums.

Dylan has strong spiritual beliefs and he has “always thought that there’s a superior power.” Although Dylan was raised in a small, close-knit Jewish community, and even had his Bar Mitzvah when he was 13, he converted to Christianity in the late 1970s and has released three popular albums of contemporary gospel music.

Dylan’s lyrics have received detailed attention from academics and poets. In 1998 Stanford University sponsored the first international academic conference on Dylan’s work, and in 2004 Harvard Classics professor Richard Thomas created a seminar on Dylan’s song lyrics, that put him in the context of classical poets like Virgil and Homer.

Dylan has been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and has won numerous other prestigious awards, including 10 Grammy Awards, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, a Golden Globe Award, an Academy Award, a Pulitzer Prize in 2008, and a Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016. Dylan has also published eight books of drawings and paintings, and his watercolor and acrylic work has been exhibited in major art galleries around the world.

Some of the quotes that Bob Dylan is known for include:

There is nothing so stable as change.

I consider myself a poet first and a musician second. I live like a poet and I’ll die like a poet.

I change during the course of a day. I wake and I’m one person, and when I go to sleep I know for certain I’m somebody else.

I think of a hero as someone who understands the degree of responsibility that comes with his freedom.

I define nothing, not beauty not patriotism. I take each thing as it is, without prior rules about what it should be.

Yesterday’s just a memory, tomorrow is never what it’s supposed to be.

You’re going to die. You’re going to be dead. It could be 20 years, it could be tomorrow, anytime. So am I. I mean, we’re just going to be gone. The world’s going to go on without us. All right now. You do your job in the face of that, and how seriously you take yourself you decide for yourself.

Photo by Rene Burri/Magnum Photos

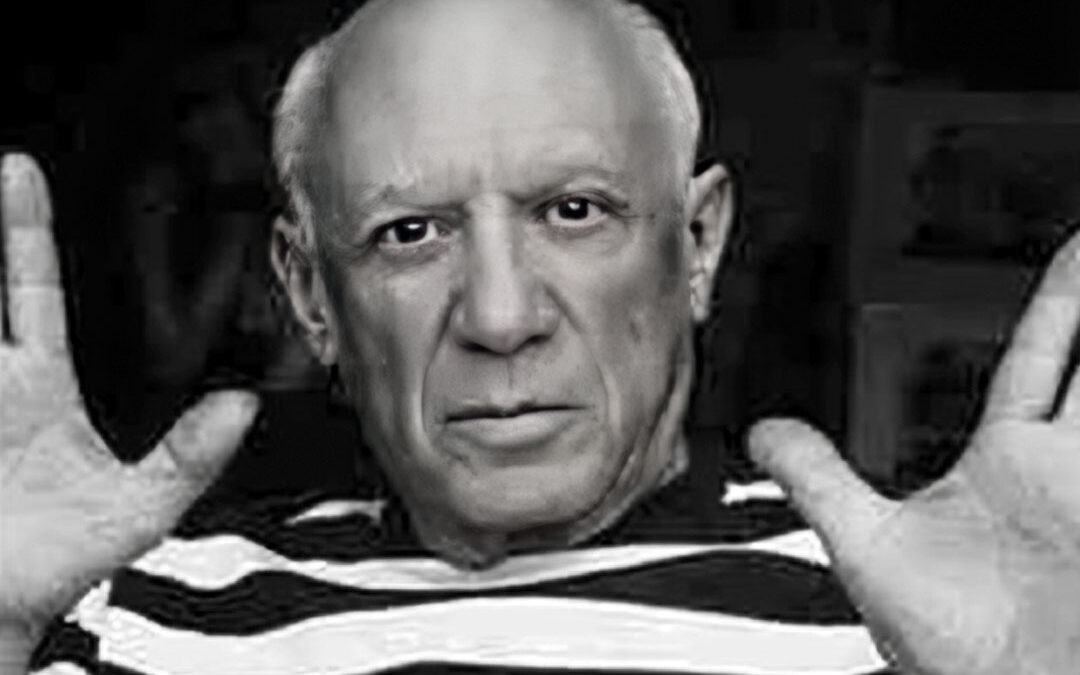

Carolyn and I have long admired the extraordinary work of the Spanish painter and sculptor Pablo Picasso, who is one of Carolyn’s all-time favorite artists, and is considered one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century.

Pablo Picasso was born in 1881 in southern Spain. His father, a painter who specialized in naturalistic depictions of birds and other animals, was a professor of art and the curator of a local museum. From an early age, Picasso demonstrated a passion for creative expression and a skill for drawing. According to his mother, Picasso’s first word was the Spanish term for “pencil.”

In 1890, at the age of seven, Picasso began his formal art training, when his father taught him figure drawing and oil painting. Since Picasso’s father was a traditional academic artist, he believed that proper training required a disciplined copying of the masters, and accurately drawing the human body from plaster casts and live models. Picasso demonstrated incredible artistic talent in his early years, painting in a naturalistic manner through his childhood and adolescence, but this rigid style of expression was destined to be re-imagined during Picasso’s career.

In 1900 Picasso moved to Paris and shared an apartment with a friend who was a writer. This was a difficult time marked by extreme poverty and much of his work was actually burned to keep their small place warm. In 1901 Picasso moved to Madrid and shared another apartment with a different writer, who wrote for a journal that Picasso illustrated. The paintings that Picasso painted from 1901 to 1904 are characterized by somber renditions of people, done mostly in shades of blue and blue-green, and this time frame is known as Picasso’s Blue Period.

By 1905 Picasso had already established himself among well-known art collectors at the time, such as Leo and Gertrude Stein. Gertrude Stein, who became Picasso’s principal patron, acquired some of Picasso’s drawings and paintings, and she exhibited them at her Parisian home in her legendary salon, which The New York Times called “the first museum of modern art.”

Between 1907 and 1909 Picasso created a series of paintings that were inspired by the African artifacts that he saw at an ethnographic museum in Paris. This became known as his “African-influenced primitivism period” and is most characterized by his famous work, Demoiselles d’Avignon, a large oil painting created in 1907, of five nude women in a Barcelona brothel, rendered with angular and disjointed body shapes.

From 1909 to 1919 Picasso’s style of work is described as Cubism. This was an art movement that revolutionized European painting and sculpture, where objects and people are broken up and reassembled in an abstract form—and instead of depicting them from a single perspective, they are painted from a multitude of different viewpoints in order to represent a greater context.

In 1917 Picasso journeyed to Italy, and here he produced work that is considered to be in a “neoclassical style.” This was an art movement that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiquity. Picasso’s paintings and drawings from this period frequently recall the work of earlier European painters Raphael and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

In 1925 some of Picasso’s work appeared at a group exhibition of Surrealist artists, and although his work at this exhibit was really more representative of Cubism, Surrealism influenced Picasso’s work during this time by reviving his interest in primitivism and eroticism.

In 1937 Picasso produced a large oil painting called Guernica which is probably his best-known work, which depicts the German bombing of a Spanish city during the Spanish Civil War. It is a powerful piece that, for many, expresses the brutality, horrors, and inhumanity of the war.

In 1939 and 1940 the Museum of Modern Art in New York City held a major retrospective of Picasso’s major works at the time, and this exhibition brought Picasso into full public view in the United States. This resulted in a reinterpretation of his work by contemporary art historians and scholars.

During the years of World War II Picasso remained in Paris while the Germans occupied the city, from 1940 to 1944. Picasso’s artistic style didn’t exactly fit in with the Nazi ideal of art, so he never exhibited his work during this time, and the Gestapo often harassed him.

During a search of his apartment, a Nazi officer saw a photograph of his painting Guernica. “Did you do that?” he asked Picasso. “No,” Picasso replied, “You did.”

Picasso’s immense creativity found its way into other mediums. Between 1935 and 1959 Picasso wrote poetry as another form of artistic expression, and he crafted over 300 poems. He also wrote two screenplays, in 1941 and 1949. Additionally, Picasso made a few film appearances as himself, including Jean Cocteau’s Testament of Orpheus in 1960, and in 1955 he helped make the film The Mystery of Picasso.

The last years of Picasso’s life were marked by a period of great creativity, during which he continued to explore new media and techniques. He also experienced great success, receiving numerous honors and awards, such as the International Lenin Peace Prize award, which he won twice, in 1950 and 1962.

Picasso’s later works often contained a mix of elements from different styles, including Cubism, Surrealism, and his own unique vision. He also continued to draw inspiration from the world around him; his paintings often contained references to current events and the political landscape at the time.

Picasso remained very active in the art world through his nineties, and he continued to exhibit his work in galleries and museums around the world until the end of his life. He also continued to work with a variety of different media, including sculpture and lithography. Picasso painted 13,500 paintings in his lifetime, and more of his paintings have been stolen than any other artist. He also produced 100,000 prints and engravings, 300 sculptures and ceramics, and 34,000 illustrations.

Picasso died in 1973 at the age of 91, and he was active as an artist until his last breath. His work has inspired generations of artists, and his influence can be seen in many of the works of modern and contemporary art. Carolyn’s painting After Picasso was inspired by Picasso’s Cubist work, for example. Picasso’s iconic pieces continue to be exhibited in museums and galleries around the world, and his influence can not only be seen in the development of modern art, but also in popular culture, with his works inspiring films, music, fashion, and other forms of artistic expression.

Some of the quotes that Picasso is known for include:

Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.

Every act of creation is first an act of destruction.

It takes a long time to become young.

The purpose of art is washing the dust of daily life off our souls.

Everything you can imagine is real.

Painting is just another way of keeping a diary.

“f there were only one truth, you couldn’t paint a hundred canvases on the same theme.

Some painters transform the sun into a yellow spot, others transform a yellow spot into the sun.

Love is the greatest refreshment in life.

I don’t believe in accidents. There are only encounters in history. There are no accidents.

The chief enemy of creativity is ‘good’ sense.

To finish a work? To finish a picture? What nonsense! To finish it means to be through with it, to kill it, to rid it of its soul, to give it its final blow the coup de grace for the painter as well as for the picture.